Are Potatoes Paleo?

I have noticed in the last few years that many Paleo Dieters believe that potatoes can be regularly consumed without any adverse health effects. Part of this misinformation seems to stem from writers of blogs and others who are unfamiliar with the scientific literature regarding potatoes.

So should we be eating potatoes or not? The short answer is no. The long answer begins with my personal experience and scientific research into the spud.

Back in the early 1980s before I had discovered Paleo, I had assumed that a low fat, high carbohydrate, plant-based diet was the best nutritional plan for good health. Little did I realize how wrong I was – I should have listened to my body.

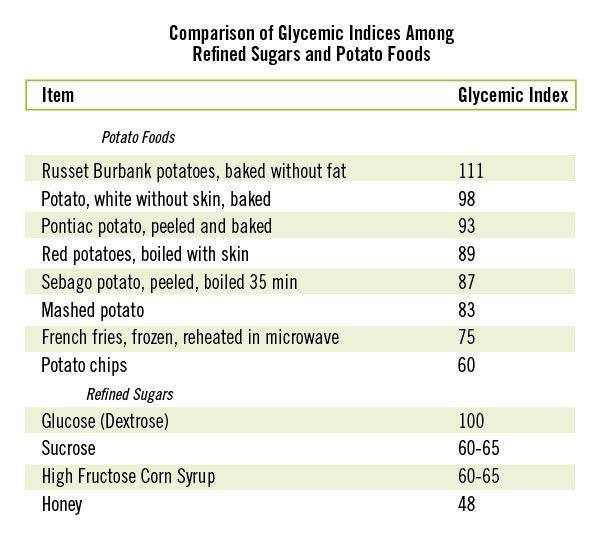

One of my personal experiences at the time was how bad early morning breakfasts of boiled potatoes made me feel. They simply left me drained of energy and feeling nervous, agitated and depressed – only a few hours after my morning meal. I lived with it. But later, after poring through the medical literature, I discovered a novel idea which could explain my symptoms. In the early 1980’s a brand new concept called the glycemic index – developed by Dr. David Jenkins at the University of Toronto had just emerged. It showed us that certain food, such as potatoes, caused our blood sugar levels to precipitously rise and then dramatically fall. It was this effect which made me feel so bad. I ate potatoes for breakfast, and they caused my blood sugar levels to spike – only to fall drastically below their original levels shortly thereafter.

In my mind, the memory of early morning, all potato breakfasts has remained with me over the years, and I now fully understand how potatoes are one of the worst foods we can eat not only for breakfast, but as staples in our diets. As with all plant foods, sporadic consumption of potatoes will have little impact upon your overall health, but if you eat them regularly as the majority of your daily calories, your health will suffer.

High glycemic index carbohydrates

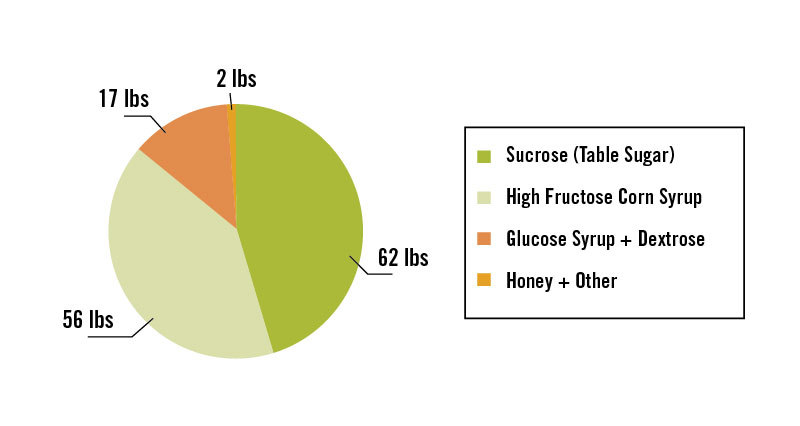

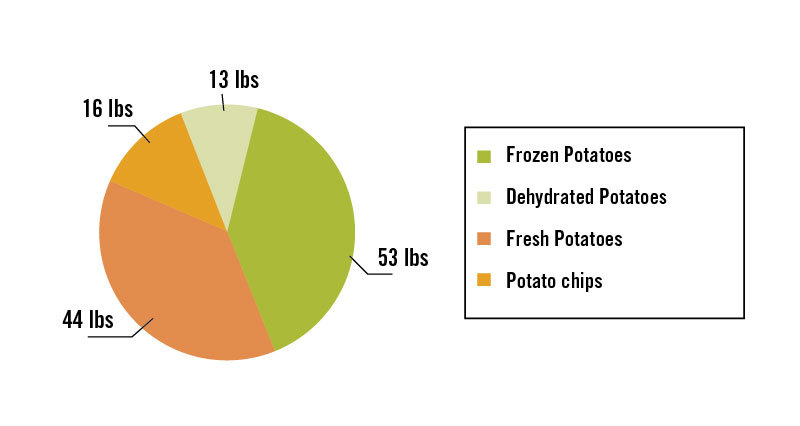

In the United States we eat a lot of potatoes. The figure below shows the per capita consumption (126 lbs) of potato foods for every person in the U.S. in 2007. If we contrast this total to all refined sugars (137 lbs per capita) in the other figure below, you can see that as a country, we eat nearly as many potatoes as we do refined sugars.

So why am I bringing up this comparison between refined sugars and potatoes? Let’s take a look at the glycemic indices of various potato foods and contrast them to refined sugars, and I think you’ll get the drift.

From the values in the table below, you can clearly see that almost all potato products have glycemic indices that are substantially higher than sucrose (table sugar) or high fructose corn syrup. So, in effect, eating potatoes is a lot like eating pure sugars, but even worse, in terms of the harm these starchy tubers do to our blood sugar levels. From this information, you can clearly see why those potato breakfasts I ate so many years ago made me feel so awful. I may have just as well been consuming pure sugar or candy bars for breakfast.

Because potatoes maintain one of the highest glycemic index values of any food, they cause our blood sugar levels to rapidly rise which in turn cause our blood insulin concentrations to simultaneously increase. When these two metabolic responses occur repeatedly over just the course of a week or two, we start to become insulin resistant – a condition that frequently precedes the development of a series of diseases known as the Metabolic Syndrome. Over the course of months and years, insulin resistance leads to a multitude of devastating health effects. The list of Metabolic Syndrome diseases is long: obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol and other abnormal blood chemistries, systemic inflammation, gout, acne, acanthosis nigricans (a skin disorder), skin tags, and breast, colon and prostate cancers.

Most of the potatoes consumed in the U.S. are highly processed in the form of French fries, mashed potatoes, dehydrated potato products, and potato chips. Processed potato foods typically are made with multiple additives (salt, vegetable oils, trans fats, refined sugars, dairy products, cereal grains and preservatives) that may adversely affect our health in a variety of ways. If these nutritional shortcomings along with their high glycemic response don’t make you wary of potatoes, then the following information almost certainly will.

Potato antinutrients

I have yet to touch upon the most dangerous elements of all within potatoes – antinutrients. More human fatalities and non-lethal poisonings have occurred from eating potatoes than from any other uncontaminated staple in our food supply.

At least 12 separate cases of human poisoning from potato consumption, involving nearly 2000 people and 30 fatalities have been recorded in the medical literature.

Saponins

I can almost guarantee you that if you ask your family physician about dietary saponins in potatoes and your health; they will draw a complete blank. The same can be said for ADA trained nutritionists at your local hospital or clinic. Even astute complementary health care practitioners are usually in the dark when it comes to saponins in our daily food supply. Despite a mountain of scientific evidence showing that these compounds can be potent and even lethal toxins, they are rarely considered as dietary threats to our health.

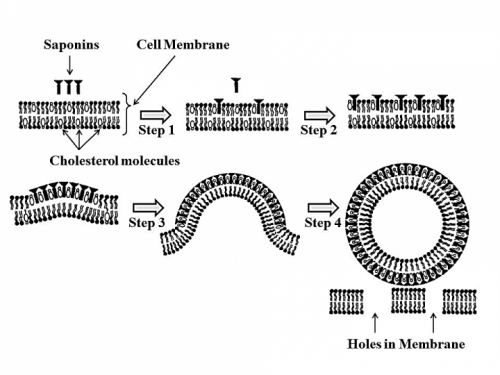

Saponins derive their name from their ability to form “soap” like foams when mixed with water. Chemically, certain potato saponins are commonly referred to as glycoalkaloids. Their function is to protect the potato plant’s root (tuber) from microbial and insect attack. When consumed by potential predators, glycoalkaloids protect the potato because they act as a toxin. These compounds exert their toxic effects by dissolving cell membranes. When rodents and larger animals, including humans, eat glycoalkaloid containing tubers such as potatoes, these substances frequently create holes in the gut lining, thereby increasing intestinal permeability. If glycoalkaloids enter our bloodstream in sufficient concentrations, they cause hemolysis (destruction of the cell membrane) of our red blood cells.

The figure below shows how glycoalkaloids and saponins in general disrupt cell membranes leading to a leaky gut or red blood cell rupturing. These compounds first bind cholesterol molecules in cell membranes, and in the series of steps that follows, you can see how saponins cause portions of the cell membrane to buckle and eventually break free, forming a pore or a hole in the membrane.

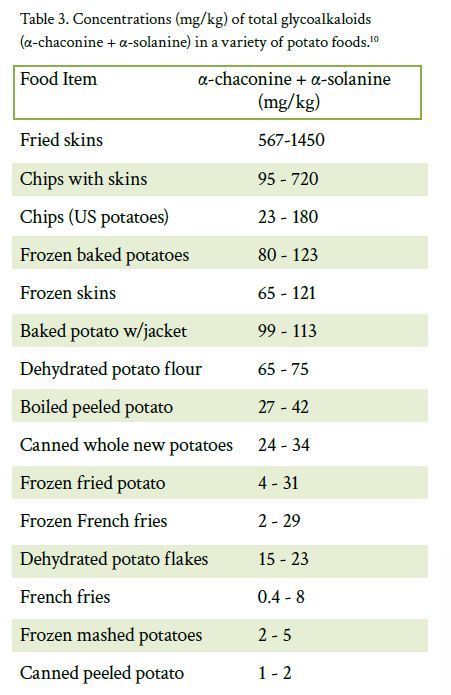

Potatoes contain two glycoalkaloid saponins: 1) α-chaconine and α-solanine which may adversely affect intestinal permeability and aggravate inflammatory bowel diseases (ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease and irritable bowel syndrome). Even in healthy normal adults a meal of mashed potatoes results in the rapid appearance of both α-chaconine and α-solanine in the bloodstream. The toxicity of these two glycoalkaloids is dose dependent – meaning that the greater the concentration in the bloodstream, the greater is their toxic effect. At least 12 separate cases of human poisoning from potato consumption, involving nearly 2000 people and 30 fatalities have been recorded in the medical literature. Potato saponins can be lethally toxic once in the bloodstream in sufficient concentrations because these glycoalkaloids inhibit a key enzyme (acetyl cholinesterase) required for nerve impulse conduction. The levels of both α-chaconine and α-solanine in a variety of potato foods are listed in the table below.

Note that the highest concentrations of these toxic glycoalkaloids occur in potato skins. Fried potato skins filled with chili and topped off by sour cream and jalapeno peppers would be a real gut bomb with devastating effects upon your intestinal permeability. And literally, if you ate enough of these hors d’oeuvres, they could kill you.

In the opinion of Dr. Patel and co-authors: “. . . if the potato were to be introduced today as a novel food it is likely that its use would not be approved because of the presence of these toxic compounds.”

So the next logical question arises: should we be eating a food that contains two known toxins which rapidly enter the bloodstream, increase intestinal permeability and potentially impair the nervous and circulatory systems?

In the opinion of Dr. Patel and co-authors: “. . . if the potato were to be introduced today as a novel food it is likely that its use would not be approved because of the presence of these toxic compounds.”

In a comprehensive review of potato glycoalkaloids, Dr. Smith and colleagues voiced similar sentiments: “Available information suggest that the susceptibility of humans to glycoalkaloids poisoning is both high and very variable: oral doses in the range 1 – 5 mg/kg body weight are marginally to severely toxic to humans whereas 3 – 6 mg/kg body weight can be lethal. The narrow margin between toxicity and lethality is obviously of concern. Although serious glycoalkaloid poisoning of humans is rare, there is a widely held suspicion that mild poisoning is more prevalent than supposed.”

The commonly accepted safe limit for total (α-chaconine + α-solanine) in potato foods is 200 mg/kg, a level proposed more than 70 years ago, whereas more recent evidence suggests this level should be lowered to 60 – 70 mg/kg. If you take a look at Table above you can see that many potato food products exceed this recommendation.

I believe that far more troubling than the toxicity of potato glycoalkaloids is their potential to increase intestinal permeability over the course of a lifetime, most particularly in people with diseases of chronic inflammation (cancer, autoimmune disease, cardiovascular disease and diseases of insulin resistance). Many scientists now believe that a leaky gut may represent a nearly universal trigger for autoimmune diseases.

When the gut becomes “leaky” it is not a good thing, as the intestinal contents may then have access to the immune system which in turn becomes activated; thereby causing a chronic low level systemic inflammation known as endotoxemia. In particular, a cell wall component of gut gram negative bacteria called lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is highly inflammatory. Any LPS which gets past the gut barrier is immediately engulfed by two types of immune system cells (macrophages and dendritic cells). Once engulfed by these immune cells, LPS binds to a receptor (toll-like receptor-4) on these cells causing a cascade of effects leading to increases in blood concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines (localized hormones).

Two recent human studies have shown that high potato diets increase the blood inflammatory marker IL-6. Without chronic low level systemic inflammation, it is unlikely that few of the classic diseases of civilization (cancer, cardiovascular disease, autoimmune diseases and diseases of insulin resistance) would have an opportunity to take hold and inflict their fatal effects.

A final note on potatoes – to add insult to injury, this commonly consumed food is a major source of dietary lectins. On average potatoes contain 65 mg of potato lectin per kilogram. As is the case with most lectins, they have been poorly studied in humans, so we really don’t have conclusive information how potato lectin may impact human health. However, preliminary tissue studies indicate that potato lectin resists degradation by gut enzymes, bypasses the intestinal barrier and can then bind various tissues in our bodies. Potato lectins have been found to irritate the immune system and produce symptoms of food hypersensitivity in allergenic and non-allergenic patients.

Cordially,

Loren Cordain, Ph.D., Professor Emeritus

References

- Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, Poggi M, Knauf C, Bastelica D et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007 Jul;56(7):1761-72.

- De Swert LF, Cadot P, Ceuppens JL. Diagnosis and natural course of allergy to cooked potatoes in children. Allergy. 2007 Jul;62(7):750-7.

- El-Tawil AM. Prevalence of inflammatory bowel diseases in the Western Nations: high consumption of potatoes may be contributing. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008 Oct;23(10):1017-8.

- Fernandes G, Velangi A, Wolever TM. Glycemic index of potatoes commonly consumed in North America. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005 Apr;105(4):557-62.

- Foster-Powell K, Holt SH, Brand-Miller JC. International table of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2002. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002 Jul;76(1):5-56.

- Francis G, Kerem Z, Makkar HP, Becker K. The biological action of saponins in animal systems: a review. Br J Nutr. 2002 Dec;88(6):587-605.

- Friedman M. Potato glycoalkaloids and metabolites: roles in the plant and in the diet.J Agric Food Chem. 2006 Nov 15;54(23):8655-81.

- Hellenäs KE, Nyman A, Slanina P, Lööf L, Gabrielsson J. Determination of potato glycoalkaloids and their aglycone in blood serum by high-performance liquid chromatography. Application to pharmacokinetic studies in humans. J Chromatogr. 1992 Jan 3;573(1):69-78.

- Henry CJ, Lightowler HJ, Strik CM, Storey M. Glycaemic index values for commercially available potatoes in Great Britain. Br J Nutr. 2005 Dec;94(6):917-21.

- Higashihara M, Ozaki Y, Ohashi T, Kume S. Interaction of Solanum tuberosum agglutinin with human platelets. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984 May 31;121(1):27-33.

- Hellenäs KE, Nyman A, Slanina P, Lööf L, Gabrielsson J. Determination of potato glycoalkaloids and their aglycone in blood serum by high-performance liquid chromatography. Application to pharmacokinetic studies in humans. J Chromatogr. 1992 Jan 3;573(1):69-78.

- Henry CJ, Lightowler HJ, Strik CM, Storey M. Glycaemic index values for commercially available potatoes in Great Britain. Br J Nutr. 2005 Dec;94(6):917-21.

- Higashihara M, Ozaki Y, Ohashi T, Kume S. Interaction of Solanum tuberosum agglutinin with human platelets. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984 May 31;121(1):27-33.

- Keukens EA, de Vrije T, van den Boom C, de Waard P, Plasman HH, Thiel F, Chupin V, Jongen WM, de Kruijff B. Molecular basis of glycoalkaloid induced membrane disruption. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995 Dec 13;1240(2):216-28.

- Keukens EA, de Vrije T, Jansen LA, de Boer H, Janssen M, de Kroon AI, Jongen WM, de Kruijff B. Glycoalkaloids selectively permeabilize cholesterol containing biomembranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996 Mar 13;1279(2):243-50.

- Leeman M, Ostman E, Björck I. Glycaemic and satiating properties of potato products. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008 Jan;62(1):87-95

- Mensinga TT, Sips AJ, Rompelberg CJ, van Twillert K, Meulenbelt J, van den Top HJ, van Egmond HP. Potato glycoalkaloids and adverse effects in humans: an ascending dose study. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2005 Feb;41(1):66-72.

- Morris SC, Lee TH. The toxicity and teratogenicity of Solanaceae glycoalkaloids, particularly those of the potato (Solanum tuberosum): a review. Food Technol, Aust. 1984;36:118-124.

- Morrow-Brown H. Clinical experience with allergy and intolerance to potto (Solanum tuberosum). Immunol Allergy Practice 1993;15:41-47

- Naruszewicz M, Zapolska-Downar D, Kośmider A, Nowicka G, Kozłowska-Wojciechowska M, Vikström AS, Törnqvist M. Chronic intake of potato chips in humans increases the production of reactive oxygen radicals by leukocytes and increases plasma C-reactive protein: a pilot study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Mar;89(3):773-7

- Patel B, Schutte R, Sporns P, Doyle J, Jewel L, Fedorak RN.Potato glycoalkaloids adversely affect intestinal permeability and aggravate inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002 Sep;8(5):340-6.

- Pramod SN, Venkatesh YP, Mahesh PA. Potato lectin activates basophils and mast cells of atopic subjects by its interaction with core chitobiose of cell-bound non-specific immunoglobulin E. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007 Jun;148(3):391-401.

- Rauchhaus M, Coats AJ, Anker SD. The endotoxin-lipoprotein hypothesis. Lancet. 2000 Sep 9;356(9233):930-3.

- Ryan, C.A. and G.M.Hass, Structural, evolutionary and nutritional properties of proteinase inhibitors from potatoes. 1981. In : Ory, R.L. (ed.), Antinutrients and natural toxicants in foods. Food and Nutrition Press Inc., Westport ,CT.

- Smith DB, Roddick JG, Jones JL. Potato glycoalkaloids: some unanswered questions. Trends Food Sci Technol 1996;7:126-131.

- Stoll LL, Denning GM, Weintraub NL. Endotoxin, TLR4 signaling and vascular inflammation: potential therapeutic targets in cardiovascular disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12(32):4229-45

- Sweet MJ, Hume DA. Endotoxin signal transduction in macrophages. J Leukoc Biol 1996;60: 8-26.

Loren Cordain, Ph.D.

As a professor at Colorado State University, Dr. Loren Cordain developed The Paleo Diet® through decades of research and collaboration with fellow scientists around the world.

More About The Author