Can Fruits and Vegetables Help Us Live Longer?

A History of the “Juice Men” Norman Walker and Jay Kordich, the Juicing Revolution, and Implications for 21st Century Health

There is a current re-emergence of ketogenic diets, which limits carbohydrate intake to less than 50 grams per day [1]. In an earlier era, however, it would have been unthinkable to restrict fresh fruit and vegetable consumption, in large part because of two generations of health-endorsing ancestors who preceded us. [2-5]

In fact, Norman Walker (1886-1985, age 99), the founder of vegetable and fruit juicing, advised consumption of unlimited vegetables, fruits, and their juices [2-4], as did Jay Kordich (1923-2017, age 93). [5]

These two men are viewed as the architects of the contemporary vegetable and fruit juicing movement. Neither were scientists, physicians, or academicians; however, their pioneering ideas regarding unrestricted consumption of fresh vegetables, fruits, and their juices were decades ahead of their times. Today, both Walker’s and Kordich’s perspectives on fresh fruit and vegetable consumption and health have been verified by contemporary peer-reviewed science.

Long before I published The Paleo Diet in 2002 [6] and before my mentor, Dr. S. Boyd Eaton wrote his groundbreaking paper, “Paleolithic Nutrition. A Consideration of its Nature and Current Implications” in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine in 1985 [7], a day and age existed before the internet, before Google, and before online PubMed when information traveled slowly, often without confirmation, validation, or scientific peer review.

In the mid 1970s, as a 20-something-year-old lifeguard at Sand Harbor, Lake Tahoe, my staff and I were totally consumed by exercise, health, fitness, and diet. We read everything we could get our hands on, and one of the major nutrition players of the day was Norman Walker, who advocated the consumption of fresh, raw vegetable and fruit juices. We picked up his books [2-4, 8-13] at the health food stores in Reno and Lake Tahoe. A few of us who could afford a juicer experimented with drinking fresh, raw vegetable and fruit juices.

At the time, I had not finished my master’s degree at the University of Nevada, Reno (1978) nor my Ph.D. at the University of Utah (1981), and of course, regular access to the internet and on-line PubMed access was still a decade or two in the future. So, at the time, it seemed reasonable to me that Norman Walker, who labeled himself as a D.Sc. and Ph.D., was a legitimate research scientist with a credible curriculum vitae dating back decades. Unfortunately, years later I learned the truth about his academic background, but this information did not diminish my respect for his anecdotal observations about fresh vegetable and fruit juice consumption and human health.

Although Norman Walker may have had a former history of unlawful activities, he will be forever known as the godfather of fresh vegetable and fruit juicing. Walker had anecdotally stumbled upon a brilliant idea.

The available evidence indicates that Norman Walker was not a Ph.D. or a D.Sc. [14] He even appears to have been a con-man in his mid-career. [14] On May 6, 1933, The New York Times reported that “An indeterminate penitentiary term of not more than three years was imposed by Judge Allen in General Sessions yesterday on Norman Walker, 47 years old.”

Beginning in 1932, this was the fifth Times article regarding Walker’s criminal activity. The original charges involved advertisements placed in the Times by Walker, as managing director for The Broughton Institute of Ortho-Dietetics in New York City, wherein he allegedly promised students employment with his school following completion of a six-week course, costing $150.

Neither employment nor the guaranteed return of the students’ $150 tuition followed. According to a probation officer testifying at the Walker trial, 30 students lost a total of $4,500 (approximately $80,000 in 2015 dollars). It is currently unknown how much incarceration time, if any, Walker served or what punishment or plea deal he eventually received. [14]

Although Norman Walker may have had a former history of unlawful activities, he will be forever known as the godfather of fresh vegetable and fruit juicing. Walker had anecdotally stumbled upon a brilliant idea. At the time in 1930, when he developed his first commercial juicer (The Triturator Juicer) [12], Walker knew virtually nothing of the molecular and evolutionary biology [2-4] that would eventually substantiate his anecdotal notions and perceptions about fresh vegetable and fruit juice consumption and health. For that matter, nor did few people from his time, simply because the molecular and evolutionary biology evidence regarding diet and health was sparse or non-existent then.

Like Walker, Jay Kordich, who came later upon the raw vegetable and fruit juicing scene, had no academic, professional, or scientific background to substantiate his views upon diet and health. [5, 15]

His ideas about health and fresh, raw fruit and vegetable juice consumption are comparable to Walker’s, and likely were based upon his personal and anecdotal observations of people who followed his recommendations to consume more fresh vegetables and fruit juices and less processed foods. Both Walker’s and Kordich’s perspectives regarding increased consumption of fresh, raw, vegetable and fruit juices are consistent with the evolutionary model of optimal human nutrition [6,7, 16-21] and randomized controlled trials (RCT) and meta-analyses of fresh fruit and vegetable consumption and positive health in humans. [22-34]

Walker lived 30.6 percent longer than the average male life expectancy for 2017. Jay Kordich lived 23.2 percent longer than the average male life expectancy for 2017.

People living to the age of 100 to 109 years are called centenarians. The CDC noted in its 2017 report that for the entire U.S. population, 2,697 females lived to the age of 100 years and beyond, while only 971 males reached this range. [35] Hence, in the U.S. in 2017 there were almost three times more centenarian women than men.

The world’s longest living people, dubbed super-centenarians, who reach the age of 110 years and beyond have been examined to further demonstrate the superior longevity of women compared to men.

In September of 2018, of all the world’s 6-7 billion people from all countries, only 1,615 supercentenarians have ever been identified and then verified. [36]

Only 148 of all supercentenarians are males which corresponds to 9.16 percent of this population, whereas 1,467 of all supercentenarians are females which equals 90.84 percent. This is a staggering difference between the genders! In other words, for every one male supercentenarian, there are nine corresponding female supercentenarians.

Norman Walker lived a very long life (99 years, 153 days), as did Jay Kordich (93 years, 274 days). Walker lived 30.6 percent longer than the average male life expectancy for 2017. Jay Kordich lived 23.2 percent longer than the average male life expectancy for 2017 (his death year).

There are obvious questions that come into play about these two anecdotal cases:

- Were Walker’s and Kordich’s long lifespans due to small and statistically un-representative sample sizes (n=2) of their diets or the genetics of these two juice men?

- Was their longevity due to a genetic predisposition for a long life from their immediate ancestors and siblings?

- Did Walker’s and Kordich’s lifelong adult ingestion of fresh fruit and vegetable juices influence their lifespans?

Of course, each of these three questions and associated hypotheses are difficult to answer objectively. Nevertheless, let’s examine each hypothesis.

- Clearly, a sample size of two represents a ridiculously small statistical sample for which little population specific information can be gleaned. However, small case studies frequently can lend insight into complex issues, particularly if the case studies are comprehensive and well detailed.

- It is possible to determine genetic lineages and lifespans for both Walker’s relatives and those of Kordich using established genealogical databases [37], and thereby obtain a glimpse of their ancestral influence upon their own longevity.

- Both the writings of Walker and Kordich are suggestive that they regularly consumed fresh, raw vegetable and fruit juices throughout their adult lives. Did this environmental/dietary factor influence their longevity?

The Case of Norman Walker

Norman Wardhaugh Walker (4 Jan 1886 – 6 Jun 1985) was born in Genoa, Italy, to Robert J. Walker, a Baptist minister from Scotland (b:1839 – d:1917, age 78) and his wife, Lydia Maw also from Scotland (b:1857 – d:1934, age 77).

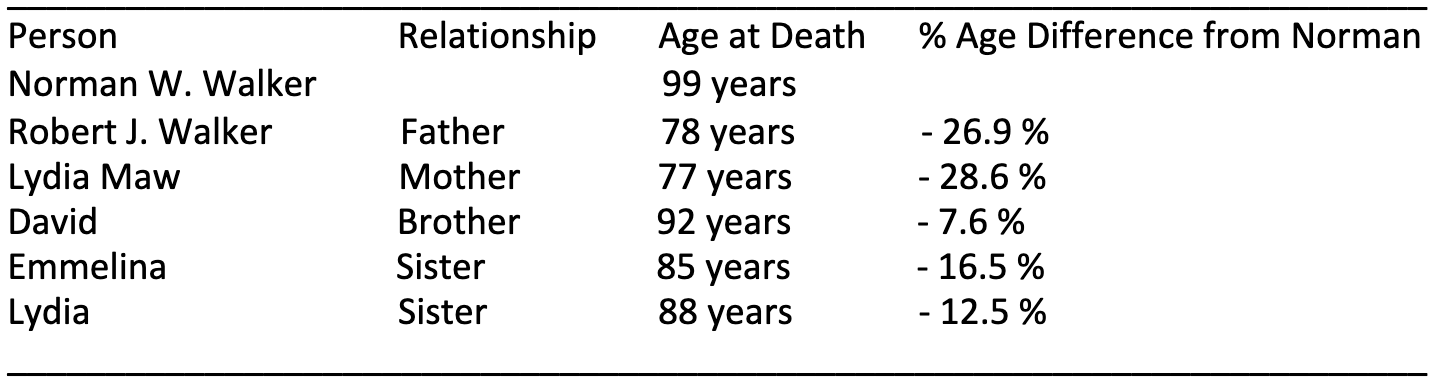

Besides Norman, Robert J. Walker and Lydia had four or perhaps five other children: David (b:1887 – d:1980, age 92), Emmelina (b:1890 – d:1975, age 85), Lydia (b:1892 – d:1980, age 88), Robert H Walker (unknown birth & death). Table 1 below indicates how much longer Norman Walker lived than either of his parents or his siblings.

Table 1. Age of Norman Walker and his Immediate Relatives [37]

The data is suggestive that Norman Walker’s long life had more to do with environmental factors (diet perhaps) than his immediate family genetics, as he far outlived all his close genetic relatives.

The Case of John Steven Kordich

John (Jay) Steven Kordich (26 Aug 1923 – 27 May 2017) was born in San Pedro, California, to Jakov (Jack) Kordich (b:1894 – d:1997, age 103), a naturalized U.S. citizen from Croatia/Yugoslavia and his wife, Vica Ilich (b:1902 – d:1999, age 97) also a naturalized U.S. citizen from Croatia/Yugoslavia.

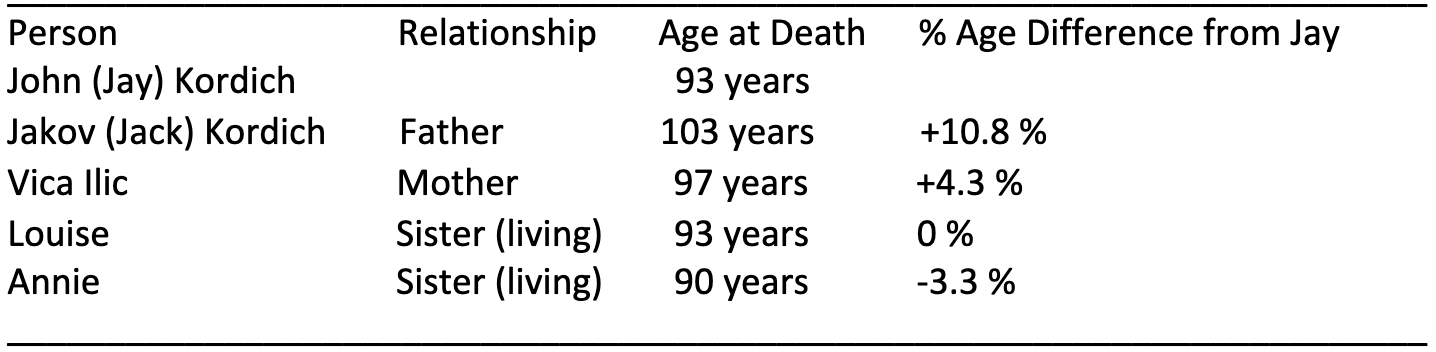

Besides their son John (Jay) Steven, Jakov and Vica had two other children, daughters Louise (b: 1925 and living today, age 93) and Annie (b: 1929 and living today, age 90). Table 2 below indicates the age differences between Jay Kordich, his longer-lived parents, and his two living sisters.

Table 2. Age of Jay Kordich and his Immediate Relatives [38]

The data in Table 2 for the Kordich family is suggestive that important genetic underpinnings may explain the extraordinary longevity in this family, but it does not exclude environmental factors such as diet.

After Jay’s father, Jakov arrived from Croatia/Yugoslavia, his life’s profession was as a fisherman in San Pedro, California. [38] Likely, the Kordich family must have had extensive access to fresh fish and crustaceans because of Jakov’s (Jack’s) profession. Increased fish consumption is known to promote health and longevity [39 – 45], likely via its concentrated source of long chain omega 3 fatty acids. [39, 43, 44]

From his anecdotal recognition of the health benefits of fresh vegetable and fruit juices in the late 1940s, Kordich became a champion and promoter of the concept that Walker had created a generation earlier, and therefore became the main modern figure associated with the massive popularity of fresh vegetable and fruit juice consumption in the early 1990s. [5, 15]

Accordingly, it is not known what influence fruit and vegetable consumption had upon Jay’s very long lifespan or that of his family, as all his immediate relatives including his father, his mother, and his sisters lived long lives, and ate fresh vegetables and fruit from their home gardens. [5]

But it is not known if Jay provided his mother, father, and sisters with commercial juicers in the 1950s through the 1990s. Thus, fresh fruit, vegetables, and fish may have played a role in the Kordich family’s impressive longevity, but the data is inconclusive [5, 15], as family genetics selecting for longevity likely were also involved. [38]

21st Century Science and the Health Benefits of Fruit and Vegetables

Although both Norman Walker and Jay Kordich dabbled in the nutritional, medical, and scientific health details of fresh, raw vegetable and fruit juice consumption, neither man had a verifiable academic, medical, or scientific background in the concept. [5, 14, 15]

Clearly both of their vast anecdotal experiences with patients cannot be ignored. [2-5] However, without present day biochemical, physiological, medical, and evolutionary data [16-34] regarding vegetable and fruit consumption, the health ramifications of raw, fresh, juice consumption could have only remained an unverified belief system for these two early health pioneers in their day and age.

Nowadays, however, the consequences of fruit and vegetable consumption on, for example, electrolyte balance is well documented.

With real, contemporary Paleo Diets [66-69], you won’t have to worry about the K+/Na ratio because those Paleo Diets don’t contain added salt, and a Paleo Diet allows you unlimited consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables.

In human nutrition, two major electrolyte pairs (potassium to sodium and calcium to magnesium) play crucial roles in health and disease. Plasma and intracellular calcium (Ca2+) concentrations affect magnesium (Mg2+) concentrations and vice versa. [46-51] Similarly, plasma and intracellular potassium (K+) concentrations affect sodium (Na+) concentrations and vice versa. [52-61]

The dietary relationship between K+ and Na+ in human nutrition and adverse health is well known and incontrovertible. [52-61] High dietary sodium intakes and low potassium ingestion increase the risk for numerous chronic diseases including cardiovascular disease, hypertension, stroke, cancer, kidney disease, and autoimmunity among others. [52-61]

The current dietary K+/Na+ ratio in the U.S. has a value of 0.76 [62], which is 2.6 times lower (worse) than recommended values of 2.0 [63, 64] and 6.6 times lower (worse) than the estimated K+/Na+ ratios of greater than 5.0 found in ancestral human diets. [65]

With real, contemporary Paleo Diets [66-69], you won’t have to worry about the K+/Na ratio because those Paleo Diets don’t contain added salt, and The Paleo Diet allows you unlimited consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables. [66-69]

These guidelines ensure that your K+/Na ratio will be greater than 5.0 like our hunter gatherer ancestors. [21, 65, 69, 70] Accordingly, the ratio of your intake of potassium-rich and low-sodium fruits and veggies (Table 3) has an enormous impact upon your health and wellbeing.

Table 3. Potassium and sodium content of fresh fruits and vegetables.

| Vegetables (n=47) | Na (mg)/1000 kcal | K (mg)/1000 kcal | K/Na (mg/mg) |

| Beet greens | 10273 | 34636 | 3.37 |

| New Zealand spinach | 9286 | 9286 | 1.00 |

| Swiss chard | 8950 | 27450 | 3.07 |

| Celery | 5000 | 16250 | 3.25 |

| Water cress | 3727 | 30000 | 8.05 |

| Bok choy | 3091 | 33725 | 10.91 |

| Purslane | 2813 | 30875 | 10.98 |

| Chicory greens | 1957 | 18261 | 9.33 |

| Leaf lettuce | 1867 | 12933 | 6.93 |

| Dandelion | 1689 | 8822 | 5.22 |

| Endive | 1294 | 18471 | 14.27 |

| Turnip greens | 1250 | 9250 | 7.40 |

| Artichoke | 1132 | 5396 | 4.77 |

| Arugla | 1080 | 14760 | 13.67 |

| Green onion | 1021 | 8625 | 8.45 |

| Lamb’s quarters | 1000 | 110512 | 10.51 |

| Broccoli | 969 | 9283 | 9.58 |

| Mustard greens | 962 | 13615 | 14.16 |

| Radicchio | 957 | 13130 | 13.75 |

| Kale | 860 | 8940 | 10.40 |

| Cauliflower | 794 | 7910 | 9.97 |

| Green cabbage | 720 | 6800 | 9.44 |

| Iceberg lettuce | 714 | 10071 | 14.10 |

| Collard greens | 667 | 5633 | 8.45 |

| Napa cabbage | 563 | 2925 | 5.25 |

| Grape leaves | 558 | 2925 | 5.25 |

| Spaghetti squash | 548 | 3484 | 6.25 |

| Zucchini squash | 471 | 15353 | 32.63 |

| Butterhead (Bibb) lettuce | 385 | 17935 | 46.63 |

| Tomato | 278 | 13167 | 47.40 |

| Okra | 258 | 9774 | 37.88 |

| Jalapeno peppers | 241 | 11724 | 48.57 |

| Mushroom | 227 | 14455 | 63.60 |

| Brussel sprouts | 210 | 3170 | 15.10 |

| Sorrel | 182 | 17727 | 97.52 |

| Hubbard squash |

160 | 7160 | 44.75 |

| Bell pepper | 150 | 8742 | 58.37 |

| Cucumber | 133 | 9800 | 73.50 |

| Summer squash | 125 | 16375 | 131.00 |

| Palm hearts | 122 | 15704 | 129.00 |

| Poblano chili | 119 | 5763 | 48.56 |

| Crookneck squash | 105 | 11684 | 110.99 |

| Butternut squash | 100 | 7100 | 71.00 |

| Asparagus | 98 | 10095 | 102.90 |

| Eggplant | 83 | 9583 | 115.00 |

| Acorn squash | 71 | 7804 | 109.25 |

| Pumpkin | 38 | 13077 | 340.00 |

| Tomatillo | 31 | 8375 | 268.00 |

| Mean | 1403 | 12927 | 46.68 |

| Fruits (n=1) | Na (mg)/1000 kcal | K (mg)/1000 kcal | k/Na (mg/mg) |

| Honeydew melon | 500 | 6333 | 12.70 |

| Cantaloupe | 471 | 7853 | 16.70 |

| Casaba melon | 321 | 6500 | 20.22 |

| Salmon berries | 298 | 2340 | 7.86 |

| Passion fruit | 289 | 3588 | 12.43 |

| Mulberries | 233 | 4512 | 19.40 |

| Papaya | 186 | 4219 | 22.68 |

| Kumquat | 141 | 2620 | 18.60 |

| Cactus pear | 122 | 5366 | 44.00 |

| Chayote | 105 | 6579 | 62.50 |

| Cherimoya | 93 | 3827 | 41.00 |

| Elderberries | 82 | 3836 | 46.67 |

| Quince | 70 | 3456 | 49.25 |

| Lime | 67 | 3400 | 51.00 |

| Star fruit | 65 | 4290 | 66.50 |

| Lemon | 50 | 7250 | 145.00 |

| Kiwi fruit | 49 | 5115 | 104.00 |

| Avocado | 48 | 3036 | 63.50 |

| Cranberries | 44 | 1853 | 42.49 |

| Tangerine | 38 | 3132 | 83.00 |

| Pomegranate | 36 | 2843 | 78.67 |

| Oheloberries | 36 | 1357 | 38.00 |

| Watermelon | 33 | 3733 | 112.00 |

| Plantain | 33 | 4090 | 124.75 |

| Strawberry | 31 | 4781 | 153.00 |

| Chokecherries (wild) | 31 | 2340 | 75.80 |

| Guava | 29 | 6132 | 208.50 |

| Grape | 29 | 2768 | 95.50 |

| Blackberries | 23 | 3767 | 162.00 |

| Gooseberries | 23 | 4500 | 198.00 |

| Boysenberries | 20 | 2780 | 139.00 |

| Pineapple | 20 | 2180 | 109.00 |

| Breadfruit | 19 | 4757 | 245.00 |

| Raspberries | 19 | 2904 | 151.00 |

| Apple | 19 | 2058 | 107.00 |

| Loganberries | 18 | 2636 | 145.00 |

| Pear | 18 | 2141 | 119.00 |

| Blueberries | 18 | 1351 | 77.00 |

| Mango | 17 | 2800 | 168.00 |

| Grapefruit | 16 | 3214 | 207.00 |

| Lychee | 15 | 2591 | 171.00 |

| Banana | 11 | 4022 | 358.00 |

| Persimmon | 8 | 2441 | 310.00 |

| Orange | 2 | 3851 | 2386.60 |

| Nectarine | 2 | 4568 | 2849.20 |

| Peach | 2 | 4872 | 2850.00 |

| Plum | 1 | 3413 | 2591.50 |

| Sweet cherry | 1 | 3524 | 3420.50 |

| Mean | 79 | 3782 | 387.07 |

These dietary electrolyte characteristics (high K+ and low Na+) reduce morbidity (disease incidence) and mortality (death) from all causes combined. [52-61]

In contrast, the typical American Diet displays a low K+/Na+ ratio of 0.76 [62] because it is dominated by high salt, processed foods such as whole grain and refined breads, cheeses, processed meats (ham, bacon, salami etc.), chips, pizza, sandwiches, tacos, condiments (ketchup, mustard, mayo etc.), and high-salt salad dressings.

The top 10 sources of salt in the U.S. diet, which greatly contribute to the dangerously low K+/Na+ ratio from processed foods in the American diet, are listed below. [71]

- Breads and rolls

- Cold cuts and cured meats (hot dogs, bologna, salami, liverwurst, sausage, etc.)

- Pizza

- Poultry (breaded chicken, chicken wings, Kentucky Fried Chicken, chicken nuggets, enchilada chicken, chicken tacos, supermarket roasted chickens, etc.)

- Soups

- Sandwiches (all)

- Cheeses (all)

- Pasta dishes (all)

- Meat dishes (processed meats, salt flavored meats, meat sticks, jerky, taco meats, etc.)

- Snacks (chips, crackers, tortilla chips, Pringles, potato chips, etc.)

The Importance of Magnesium and Calcium Interactions

In human nutrition, the dietary Ca2+/Mg2+ ratio maintains a huge effect upon our health and well-being. Ca2+/Mg2+ ratios of less than 1.7 and greater than 2.8 are detrimental. [46] High dietary values (greater than 2.8) for the Ca2+/Mg2+ ratio may increase the risk for cardiovascular disease, particularly from increased artery calcification. [48-51]

Typical Western diets cause Ca2+/Mg2+ imbalances because of their reliance upon dairy products, which are low in magnesium but high in calcium. This is particularly true of calcium-rich cheeses that provide a huge average Ca2+/Mg2+ ratio of 23.9 [72, 73] (see tables 5 and 6), which further increase the dietary imbalance between calcium and magnesium.

Table 5. Calcium and magnesium content of dairy foods [72, 73]

| Food | Calcium (mg/100g) | Magnesium (mg/100g) | Calcium/Magnesium Ratio (mg/100g) |

| Butter | 24.0 | 2.0 | 12.0 |

| Whole milk | 113.0 | 10.0 | 11.3 |

| Cheeses (n=36) | 611.5 | 26.6 | 23.9 |

| Yogurt (plain, low fat) | 183.0 | 17.0 | 10.8 |

Table 6. Calcium and magnesium content in various cheeses [72, 73]

| Cheese | Calcium | Magnesium | Ca/Mg |

| Roquefort | 662 | 30 | 22.1 |

| Parmesan | 1109 | 38 | 29.2 |

| Blue | 528 | 23 | 23.0 |

|

American, processed | 552 | 27 | 20.4 |

| Romano | 1064 | 41 | 26.0 |

| Feta | 483 | 19 | 25.9 |

| Edam | 731 | 30 | 24.4 |

| Provolone |

756 | 28 | 27.0 |

| Camembert | 388 | 20 | 19.4 |

| Gouda | 700 | 29 | 24.1 |

| Fontina | 550 | 14 | 39.3 |

| Limburger | 497 | 21 | 23.7 |

| Tilsit | 700 | 13 | 53.8 |

| Queso Fresco | 566 | 24 | 23.6 |

| Queso Blanco | 690 | 29 | 23.8 |

| Cheshire | 643 | 21 | 30.6 |

| Caraway | 673 | 22 | 30.6 |

| Queso Asadero | 661 | 26 | 25.4 |

| Brie | 184 | 20 | 9.2 |

| Muenster | 717 | 27 | 26.6 |

| Cheddar | 721 | 28 | 25.8 |

| Mozzarella | 782 | 23 | 34.0 |

| Colby | 685 | 26 | 26.3 |

| Gjetost | 400 | 70 | 5.7 |

| Calzone | 425 | 26 | 16.3 |

| Brick | 674 | 24 | 28.1 |

| Monterey Jack | 746 |

27 | 27.6 |

| Port du Salut | 650 | 24 | 27.1 |

| Goat (hard) | 895 | 54 | 16.6 |

| Gruyere | 1011 | 36 | 28.1 |

| Neufchatel | 117 | 10 | 11.7 |

| Cottage 2% fat | 91 | 7 | 13.0 |

| Cream cheese | 98 | 9 | 10.9 |

| Swiss | 791 | 38 | 20.8 |

| Emmental Swiss | 791 | 38 | 20.8 |

| Ricotta (part skim) | 272 | 15 | 18.1 |

|

Mean | 611.5 | 26.6 | 23.9 |

Unlike dairy products, with their exorbitantly high calcium to magnesium ratios (23.9), fresh vegetables (Ca2+/Mg2+ = 2.56) (Table 7) and fruits (Table 8) maintain lower, more favorable Ca2+/Mg2+ ratios which generally fall between known healthful values of 1.7 and 2.8. [46]

Table 7. Calcium and magnesium content in vegetables

| Vegetables | Mg/100g | Ca/100g | Ca/Mg |

| Sorrel | 102.1 | 44.0 | 0.43 |

| Swiss Chard | 81.0 | 51.0 | 0.63 |

| Purslane | 68.0 | 65.0 | 0.96 |

| Spinach | 79.0 | 99.0 | 1.25 |

| Beet greens | 70.0 | 117.0 | 1.67 |

| New Zealand spinach | 39.0 | 58.0 | 1.49 |

| Pumpkin leaves | 38.0 | 39.0 | 1.03 |

| Watercress | 21.0 | 120.0 | 5.71 |

| Arugula | 47.0 | 160.0 | 3.40 |

| Okra | 57.0 | 81.0 | 1.42 |

| Sweet potato leaves | 61.0 | 37.0 | 0.61 |

| Parsley | 50.0 | 138.0 | 2.76 |

| Nopales (cactus leaves) | 22.0 | 164.0 | 7.46 |

| Chicory greens | 30.0 | 100.0 | 3.33 |

| Mustard greens | 32.0 | 103.0 | 3.22 |

| Crookneck squash | 17.0 | 15.0 | 0.88 |

| Zucchini squash | 18.0 | 16.0 | 0.89 |

| Grape leaves | 95.0 | 363.0 | 3.82 |

| Rapini (broccoli raab) | 22.0 | 108.0 | 4.91 |

| Butterhead (Bibb) lettuce | 13.0 | 35.0 | 2.69 |

| Turnip greens | 31.0 | 190.0 | 6.31 |

| Bok choy (Chinese cabbage) | 11.0 | 68.8 | 6.26 |

| Endive (Escaroie) | 15.0 | 52.0 | 3.47 |

| Cucumber | 13.0 | 16.0 | 1.23 |

| Romaine lettuce | 14.0 | 33.0 | 2.36 |

| Napa (Chinese) cabbage | 13.0 | 77.0 | 5.92 |

| Dandelion greens | 36.0 | 187.0 | 5.19 |

| Acorn squash | 32.0 | 33.0 | 1.03 |

| Artichoke | 42.0 | 21.0 | 0.50 |

| Lamb’s quarters | 34.0 | 309.0 | 9.09 |

| Collard greens | 20.0 | 140.0 | 7.00 |

| Lettuce, red leaf | 12.0 | 33.0 | 2.75 |

| Butternut squash | 29.0 | 41.0 | 1.41 |

| Kohlrabi | 19.0 | 24.0 | 1.26 |

| Asparagus | 14.0 | 24.0 | 1.71 |

| Celery | 11.0 | 40.0 | 3.64 |

| Kale | 34.0 | 135.0 | 3.97 |

| Tomatillo | 20.0 | 7.0 | 0.35 |

| Broccoli | 21.0 | 47.0 | 2.24 |

| Tomato | 11.0 | 10.0 | 0.91 |

| Jalapeno pepper | 15.0 | 12.0 | 0.80 |

| Cauliflower | 15.0 | 22.0 |

1.47 |

| Radicchio leaves | 13.0 | 19.0 | 1.46 |

| Brussel sprouts | 23.0 | 42.0 | 1.83 |

| Eggplant | 14.0 | 9.0 | 0.64 |

| Fennel bulb | 17.0 | 49.0 | 2.88 |

| Cabbage, red | 16.0 | 45.0 | 2.81 |

| Bell pepper | 10.0 | 10.0 | 1.00 |

| Iceberg lettuce | 7.0 | 18.0 | 2.57 |

| Cabbage, green | 12.0 | 40.0 | 3.33 |

| Pumpkin | 12.0 | 21.0 | 1.75 |

| Mushrooms, white | 9.0 | 3.0 | 0.33 |

| Squash, spaghetti | 11.0 | 21.0 | 1.91 |

| Palm hearts | 10.0 | 18.0 | 1.8 |

| Loose leaf (green leaf) lettuce | 13.0 | 36.0 | 2.77 |

| Mean | 28.9 | 67.6 | 2.56 |

Table 8. Calcium and magnesium content in fruits [72,73]

| Fruit | Mg/100g | Ca/100g | Ca/Mg |

| Cactus figs | 85.0 | 56.0 | 0.66 |

| Lemon | 12.0 | 61.0 | 5.08 |

| Blackberries | 20.0 | 29.0 | 1.45 |

| Raspberries | 22.0 | 25.0 | 1.14 |

| Mulberries | 18.0 | 39.0 | 2.17 |

| Starberries | 13.0 | 16.0 | 1.23 |

| Casaba melon | 11.0 | 11.0 | 1.0 |

| Guava | 22.0 | 18.0 | 0.82 |

| Cantaloupe | 12.0 | 9.0 | 0.75 |

| Loganberries | 12.0 | 9.0 | 0.75 |

| Watermelon | 10.0 | 7.0 | 0.70 |

| Star fruit | 10.0 | 3.0 | 0.30 |

| Boysenberries | 16.0 | 27.0 | 1.69 |

| Banana | 27.0 | 5.0 | 0.19 |

| Plantain | 37.0 | 3.0 | 0.08 |

| Passion fruit | 29.0 | 12.0 | 0.41 |

| Kumquats | 20.0 | 62.0 | 3.10 |

| Kiwi fruit | 17.0 | 34.0 | 2.00 |

| Honeydew melon | 10.0 | 6.0 | .60 |

| Payaya | 21.0 | 20.0 | 0.95 |

| Pineapple | 12.0 | 13.0 | 1.08 |

| Peach | 9.0 | 6.0 | 0.87 |

| Cherimoya | 17.0 | 10.0 | 0.59 |

| Gooseberries | 10.0 | 25.0 | 2.50 |

| Grapefruit | 9.0 | 22.0 | 2.44 |

| Orange | 10.0 | 40.0 | 4.00 |

| Nectarine | 9.0 | 6.3 | 0.67 |

| Lime | 6.0 | 33.0 | 5.50 |

| Tangerine | 12.0 | 37.0 | 3.08 |

| Sweet cherry | 11.0 | 13.0 | 1.18 |

| Avocado | 29.0 | 13.0 | 0.45 |

| Chockecherries | 27.0 |

60.0 | 2.22 |

| Mango | 10.0 | 11.0 | 1.1 |

|

Lychees | 10.0 | 5.0 | 0.5 |

| Plum | 7.0 | 6.0 | 0.86 |

| Pomegranate | 12.0 | 10.0 | 0.83 |

| Quince | 8.0 | 11.0 | 1.38 |

| Cranberries | 6.0 | 8.0 | 1.33 |

| Persimmons | 9.0 | 8.0 | 0.89 |

| Pear | 7.0 | 9.0 | 1.29 |

| Blueberries | 6.0 | 6.0 | 1.0 |

| Apple | 5.0 | 6.0 | 1.0 |

| Grapes (red or green) |

7.0 | 10.0 | 1.43 |

| Elderberries | 5.0 | 38.0 | 7.6 |

| Salmon berries | 15.0 | 13.1 | 0.87 |

| Oheloberries | 6.0 | 7.0 | 1.17 |

| Chayote | 12.0 | 17.0 | 1.41 |

| Mean | 10.6 | 14.0 | 1.5 |

Ahead of Their Time

Both Norman Walker and Jay Kordich lived extraordinary long and healthful lives. They were both health pioneers who followed their dietary recommendations for increased fruit and vegetable juice consumption. Neither of these men were scientists or biologists who fully understood the evolutionary and physiological basis for their diet-based health recommendations.

Nevertheless, their ideas about diet and health have stood the test of time. As we move objectively into the 21st century, comprehending our humble evolutionary background from anaerobic bacteria to more complex eukaryotic life forms with nuclei and mitochondria, it is clear that the basic longevity lessons, unknown scientifically to Walker and Kordich, are now compelling objective truths.

Acknowledgements

For Anthony (Tony) Sebastian M.D., a gentle soul and a mastermind of certain data contained within this manuscript.

References

- https://thepaleodiet.com/ketogenic-diets-long-term-nutritional-and-metabolic-deficiencies/

- Walker NW. Raw Vegetable Juices: What’s Missing in Your Body? (1936). Norwalk Press.

- Walker NW. Diet & Salad Suggestions, for use in connection with vegetable and fruit juices (1940). Norwalk Press.

- Walker NW. Become Younger (1949). Norwalk Press.

- Kordich J. The Juiceman’s Power of Juicing (1992). William Morrow and Company, Inc.

- Cordain L. The Paleo Diet. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY, 2002.

- Eaton SB, Konner M. Paleolithic nutrition. A consideration of its nature and current implications. N Engl J Med. 1985 Jan 31;312(5):283-9.

- Walker NW. Are You Slipping? (1961). Norwalk Press.

- Walker NW. The Natural Way to Vibrant Health (1972). Norwalk Press.

- Walker NW. Water Can Undermine Your Health (1974). Norwalk Press.

- Walker NW. Back to the Land … for Self Preservation: a freedom, life-style, and nutritional commentary (1977). Norwalk Press.

- Walker NW. Colon Health: The Key to a Vibrant Life (1979). Norwalk Press.

- Walker NW. Pure & Simple Natural Weight Control (1981). Norwalk Press.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Norman_W._Walker

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juiceman_Juicer

- Cordain L, Brand Miller J, Eaton SB, Mann N, Holt SHA, Speth JD. Plant to animal subsistence ratios and macronutrient energy estimations in world wide hunter-gatherer diets. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2000, 71:682-92.

- Cordain L. The nutritional characteristics of a contemporary diet based upon Paleolithic food groups. J Am Neutraceut Assoc 2002; 5:15-24.

- Lindeberg S, Cordain L, Eaton B. Biological and clinical potential of a Palaeolithic diet. J Nutr Environ Med 2003; 13:149-160.

- O’Keefe J.H., Cordain L. Cardiovascular disease as a result of a diet and lifestyle at odds with our Paleolithic genome: how to become a 21st century hunter-gatherer. Mayo Clin Proc 2004; 79:101-108.

- Cordain L, Eaton SB, Sebastian A, Mann N, Lindeberg S, Watkins BA, O’Keefe JH, Brand-Miller J. Origins and evolution of the western diet: Health implications for the 21st century. Am J Clin Nutr 2005; 81:341-54.

- Carrera-Bastos P, Fontes Villalba M, O’Keefe JH, Lindeberg S, Cordain L. The western diet and lifestyle and diseases of civilization. Res Rep Clin Cardiol 2011; 2: 215-235.

- Kojima G, Avgerinou C, Iliffe S, Jivraj S, Sekiguchi K, Walters K. Fruit and Vegetable Consumption and Frailty: A Systematic Review. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22(8):1010-1017

- Hosseini B, Berthon BS, Saedisomeolia A, Starkey MR, Collison A, Wark PAB, Wood LG. Effects of fruit and vegetable consumption on inflammatory biomarkers and immune cell populations: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018 Jul 1;108(1):136-155

- Zhang Y, Zhang DZ. Associations of vegetable and fruit consumption with metabolic syndrome. A meta-analysis of observational studies. Public Health Nutr. 2018 Jun;21(9):1693-1703

- Mottaghi T, Amirabdollahian F, Haghighatdoost F. Fruit and vegetable intake and cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018 Oct;72(10):1336-1344

- Tian Y, Su L, Wang J, Duan X, Jiang X. Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of the metabolic syndrome: a meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2018 Mar;21(4):756-765.

- Zhang S, Jia Z, Yan Z, Yang J. Consumption of fruits and vegetables and risk of renal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Oncotarget. 2017 Apr 25;8(17):27892-27903.

- Hosseini B, Berthon BS, Wark P, Wood LG. Effects of Fruit and Vegetable Consumption on Risk of Asthma, Wheezing and Immune Responses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2017 Mar 29;9(4).

- Zheng J, Zhou Y, Li S, Zhang P, Zhou T, Xu DP, Li HB. Effects and Mechanisms of Fruit and Vegetable Juices on Cardiovascular Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2017 Mar 4;18(3).

- Jiang X, Huang J, Song D, Deng R, Wei J, Zhang Z. Increased Consumption of Fruit and Vegetables Is Related to a Reduced Risk of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia: Meta-Analysis. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017 Feb 7; 9:18

- Sahebkar A, Ferri C, Giorgini P, Bo S, Nachtigal P, Grassi D. Effects of pomegranate juice on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacol Res. 2017 Jan; 115:149-161

- Wu L, Sun D, He Y. Fruit and vegetables consumption and incident hypertension: dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Hum Hypertens. 2016 Oct;30(10):573-80

- Benetou V, Orfanos P, Feskanich D, Michaëlsson K, Pettersson-Kymmer U, Eriksson S, Grodstein F, Wolk A, Bellavia A, Ahmed LA, Boffeta P, Trichopoulou A. Fruit and Vegetable Intake and Hip Fracture Incidence in Older Men and Women: The CHANCES Project. J Bone Miner Res. 2016 Sep;31(9):1743-52.

- Benetou V, Orfanos P, Feskanich D, Michaëlsson K, Pettersson-Kymmer U, Eriksson S, Grodstein F, Wolk A, Bellavia A, Ahmed LA, Boffeta P, Trichopoulou A. Fruit and Vegetable Intake and Hip Fracture Incidence in Older Men and Women: The CHANCES Project. J Bone Miner Res. 2016 Sep;31(9):1743-52

- https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr68/nvsr68_07-508.pdf

- http://www.grg.org/ (updated 21 Sep 2018).

- www.ancestry.com (search of Norman Wardhaugh Walker, 4 Jan 1886 to 6 Jun 1985)

- www.ancestry.com (search of John Steven Kordich, 26 Aug 1923 to 27 May 2017)

- Zhang Y, Zhuang P, He W, Chen JN, Wang WQ, Freedman ND, Abnet CC, Wang JB, Jiao JJ. Association of fish and long-chain omega-3 fatty acids intakes with total and cause-specific mortality: prospective analysis of 421 309 individuals. J Intern Med. 2018 Oct;284(4):399-417

- Deng A, Pattanaik S, Bhattacharya A, Yin J, Ross L, Liu C, Zhang J. Fish consumption is associated with a decreased risk of death among adults with diabetes: 18-year follow-up of a national cohort. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2018 Oct;28(10):1012-1020

- Hengeveld LM, Praagman J, Beulens JWJ, Brouwer IA, van der Schouw YT, Sluijs I. Fish consumption and risk of stroke, coronary heart disease, and cardiovascular mortality in a Dutch population with low fish intake. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018 Jul;72(7):942-950

- Wallin A, Orsini N, Forouhi NG, Wolk A. Fish consumption in relation to myocardial infarction, stroke and mortality among women and men with type 2 diabetes: A prospective cohort study.Clin Nutr. 2018 Apr;37(2):590-596.

- Wan Y, Zheng J, Wang F, Li D. Fish, long chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids consumption, and risk of all-cause mortality: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis from 23 independent prospective cohort studies. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2017;26(5):939-956

- Villegas R, Takata Y, Murff H Blot WJ. Fish, omega-3 long-chain fatty acids, and all-cause mortality in a low-income US population: Results from the Southern Community Cohort Study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015 Jul;25(7):651-8. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2015.04.006. Epub 2015 Apr 25.43.

- Zhao LG Sun JW, Yang Y, Ma X, Wang YY, Xiang YB2. Fish consumption and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016 Feb;70(2):155-61.

- Rosanoff A, Dai Q, Shapses SA. Essential Nutrient Interactions: Does low or suboptimal magnesium status interact with vitamin d and/or calcium status? Adv Nutr. 2016 Jan 15;7(1):25-43

- Seelig MS. Increased need for magnesium with the use of combined oestrogen and calcium for osteoporosis treatment. Magnes Res. 1990 Sep;3(3):197-215.

- Park B, Kim MH, Cha CK, Lee YJ, Kim KC. High calcium-magnesium ratio in hair is associated with coronary artery calcification in middle-aged and elderly individuals. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2017 Sep;179(1):52-58

- Kousa A, Havulinna AS, Moltchanova E, Taskinen O, Nikkarinen M, Eriksson J, Karvonen M. Calcium:magnesium ratio in local groundwater and incidence of acute myocardial infarction among males in rural Finland. Environ Health Perspect. 2006 May;114(5):730-4.

- Sato H, Takeuchi Y, Matsuda K, Saito A, Kagaya S, Fukami H, Ojima Y, Nagasawa T. Evaluation of the predictive value of the serum calcium-magnesium ratio for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in incident dialysis patients. Cardiorenal Med. 2017 Dec;8(1):50-60

- Varo P. Mineral element balance and coronary heart disease. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 1974;44:367-73.

- Jansson B. Geographic cancer risk and intracellular potassium/sodium ratios. Cancer Detect Prev. 1986;9(3-4):171-94

- Jansson B. Potassium, sodium, and cancer: a review. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 1996;15(2-4):65-73.

- Judd SE, Aaron KJ, Letter AJ, Muntner P, Jenny NS, Campbell RC, Kabagambe EK, Levitan EB, Levine DA, Shikany JM, Safford M, Lackland DT. High sodium:potassium intake ratio increases the risk for all-cause mortality: the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study. J Nutr Sci. 2013 Apr 23;2:e13. doi: 10.1017/jns.2013.4.

- Umesawa M Iso H, Date C, Yamamoto A, Toyoshima H, Watanabe Y, Kikuchi S, Koizumi A, Kondo T, Inaba Y, Tanabe N, Tamakoshi A; JACC Study Group. Relations between dietary sodium and potassium intakes and mortality from cardiovascular disease: The Japan Collaborative Cohort Study for Evaluation of Cancer Risks. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008 Jul;88(1):195-202.

- Jackson SL, Cogswell ME, Zhao L, Terry AL, Wang CY, Wright J, Coleman King SM, Bowman B, Chen TC, Merritt R, Loria CM. Association between urinary sodium and potassium excretion and blood pressure among adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2014.Circulation. 2018 Jan 16;137(3):237-246

- Okayama A, Okuda N, Miura K, Okamura T, Hayakawa T, Akasaka H, Ohnishi H, Saitoh S, Arai Y, Kiyohara Y, Takashima N, Yoshita K, Fujiyoshi A, Zaid M, Ohkubo T, Ueshima H; NIPPON DATA80 Research Group. Dietary sodium-to-potassium ratio as a risk factor for stroke, cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in Japan: the NIPPON DATA80 cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016 Jul 13;6(7):e011632. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011632

- Willey J, Gardener H, Cespedes S, Cheung YK, Sacco RL, Elkind MSV. Dietary sodium to potassium ratio and risk of stroke in a multiethnic urban population: The Northern Manhattan Study. Stroke. 2017 Nov;48(11):2979-2983.

- Frassetto L, Morris RC Jr, Sellmeyer DE, Todd K, Sebastian A. Diet, evolution and aging–the pathophysiologic effects of the post-agricultural inversion of the potassium-to-sodium and base-to-chloride ratios in the human diet. Eur J Nutr. 2001 Oct;40(5):200-13.

- Sebastian A, Cordain L, Frassetto L, Banerjee T, Morris RC. Postulating the major environmental condition resulting in the expression of essential hypertension and its associated cardiovascular diseases: Dietary imprudence in daily selection of foods in respect of their potassium and sodium content resulting in oxidative stress-induced dysfunction of the vascular endothelium, vascular smooth muscle, and perivascular tissues. Med Hypotheses. 2018 Oct;119:110-119

- https://thepaleodiet.com/ketogenic-diets-long-term-nutritional-and-metabolic-deficiencies/

- Hoy MK, Goldman JD. Potassium intake of the U.S. population-what we eat in America, NHANES 2009-2010, 2012 www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/fsrg

- https://ods.od.nih.gov/Health_Information/Dietary_Reference_Intakes.aspx

- https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2000/document/choose.htm

- Frassetto L, Morris RC Jr, Sellmeyer DE, Todd K, Sebastian A. Diet, evolution and aging–the pathophysiologic effects of the post-agricultural inversion of the potassium-to-sodium and base-to-chloride ratios in the human diet. Eur J Nutr. 2001 Oct;40(5):200-13.

- Cordain L. The Real Paleo Diet Cookbook. Houghton, Mifflin, Harcourt, New York, 2015.

- Cordain L. Real Paleo Fast & Easy. Houghton, Mifflin, Harcourt, New York, 2015.

- Cordain L, Stephenson L, Cordain L. The Paleo Diet Cookbook. John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2011.

- Cordain L. The nutritional characteristics of a contemporary diet based upon Paleolithic food groups. J Am Neutraceut Assoc 2002; 5:15-24.

- Cordain L, Eaton SB, Sebastian A, Mann N, Lindeberg S, Watkins BA, O’Keefe JH, Brand-Miller J. Origins and evolution of the western diet: Health implications for the 21st century. Am J Clin Nutr 2005; 81:341-54.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: food categories contributing the most to sodium consumption – United States, 2007 – 2008, February 7, 2012.

- https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/nutrients/index

- Nutritionist Pro, Nutritional Software. Axxya Systems. http://www.nutritionistpro.com/

Loren Cordain, Ph.D.

As a professor at Colorado State University, Dr. Loren Cordain developed The Paleo Diet® through decades of research and collaboration with fellow scientists around the world.

More About The Author