Recent research study challenges the Paleolithic diet’s benefit on gut and cardiovascular health and adds that whole grain sources may be required

When you have been a proponent of Paleolithic nutrition for nearly 30 years, have read the research on its health benefits, and have knowledge of thousands of individuals that have benefited by its adoption, you receive negative research1 with a healthy dose of skepticism. That being said, one still has to examine the research and make an objective assessment to either include it in the database of relevant studies, move it into the “more research needed” column, or confidently challenge it as yet another biased attempt to discredit an important area of nutritional research.

I say this because we’ve been here before. In fact, last time we felt the research/reporting was so poor and biased, that three of us from The Paleo Diet® Team wrote articles addressing the issue. This previous research came out of Australia, as does this new research paper published by Genoni et al. claiming the Paleolithic Diet raises serum trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), a potential biomarker of cardiovascular disease (CVD). In fact, the few negative studies published about the Paleo Diet all appear to come from Australia. So, it might be worth starting by taking a quick look at some of the nutritional politics down under.

The Dietitians Association of Australia (DAA) presents itself as “the peak body for dietetic and nutrition professionals, representing more than 7,000 members around Australia and overseas.” Further, the DAA states that, “we recommend looking for the Accredited Practising Dietitian (APD) credential when choosing a dietitian.” The DAA, of course, is responsible for bestowing that title on any nutritionist wanting the same. That also means anyone coming along with something successful that they don’t own, or control, would obviously be competition and in theory could result in their member number decreasing.

So, when Australian celebrity chef, Pete Evans embraced the Paleo Diet® and simply used his skills as a chef to create recipes to share with his followers, the DAA made it a cause to discredit him at every opportunity. They have chosen to frequently attack him as unqualified and create the impression that he came up with the concept of Paleolithic nutrition, rather than address in detail the enormous body of peer-reviewed literature that supports the Paleolithic nutritional template.

“This is a remarkable statement as it is a complete misrepresentation of the facts.”

– Mark J. Smith, Ph.D.

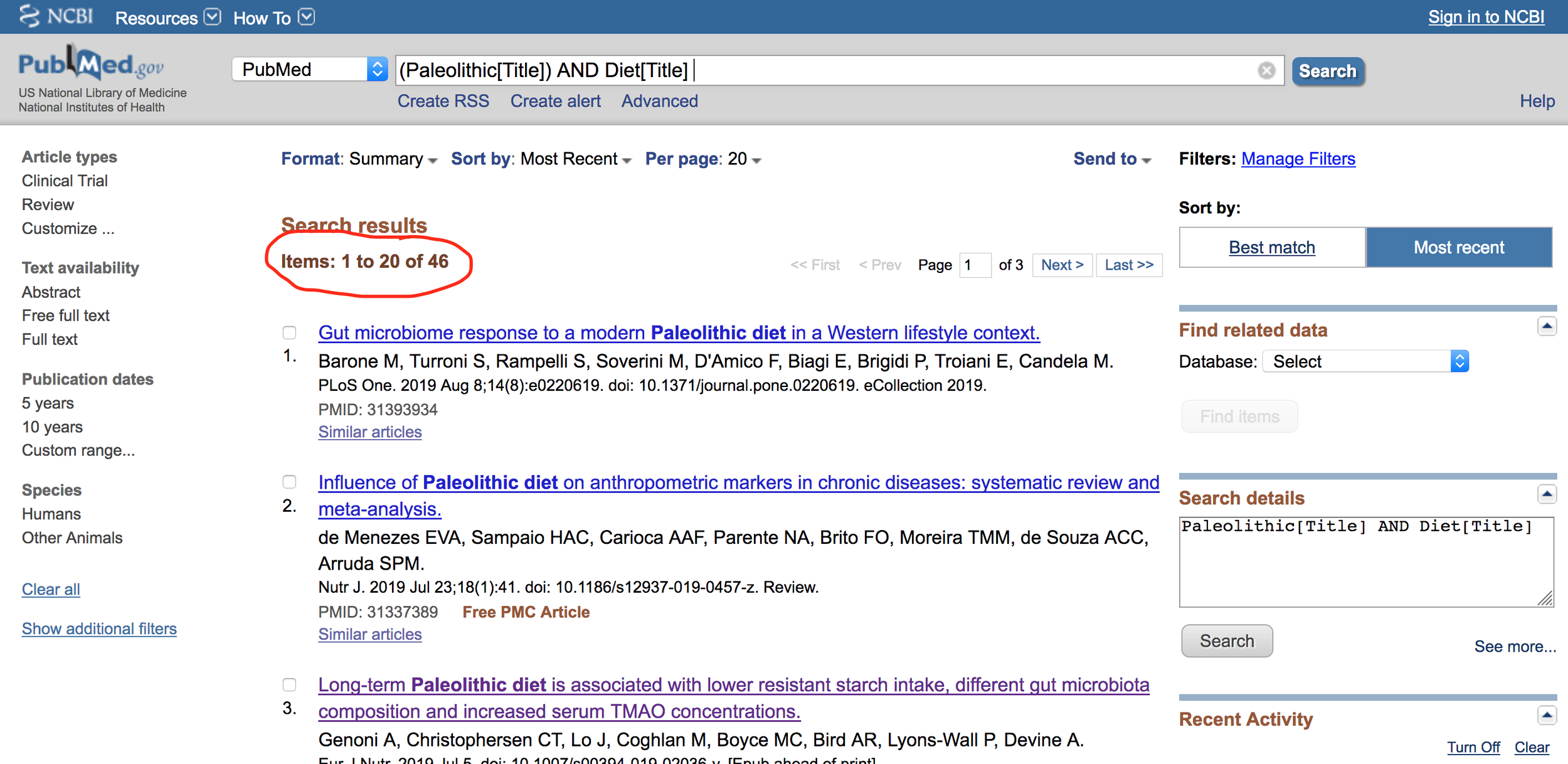

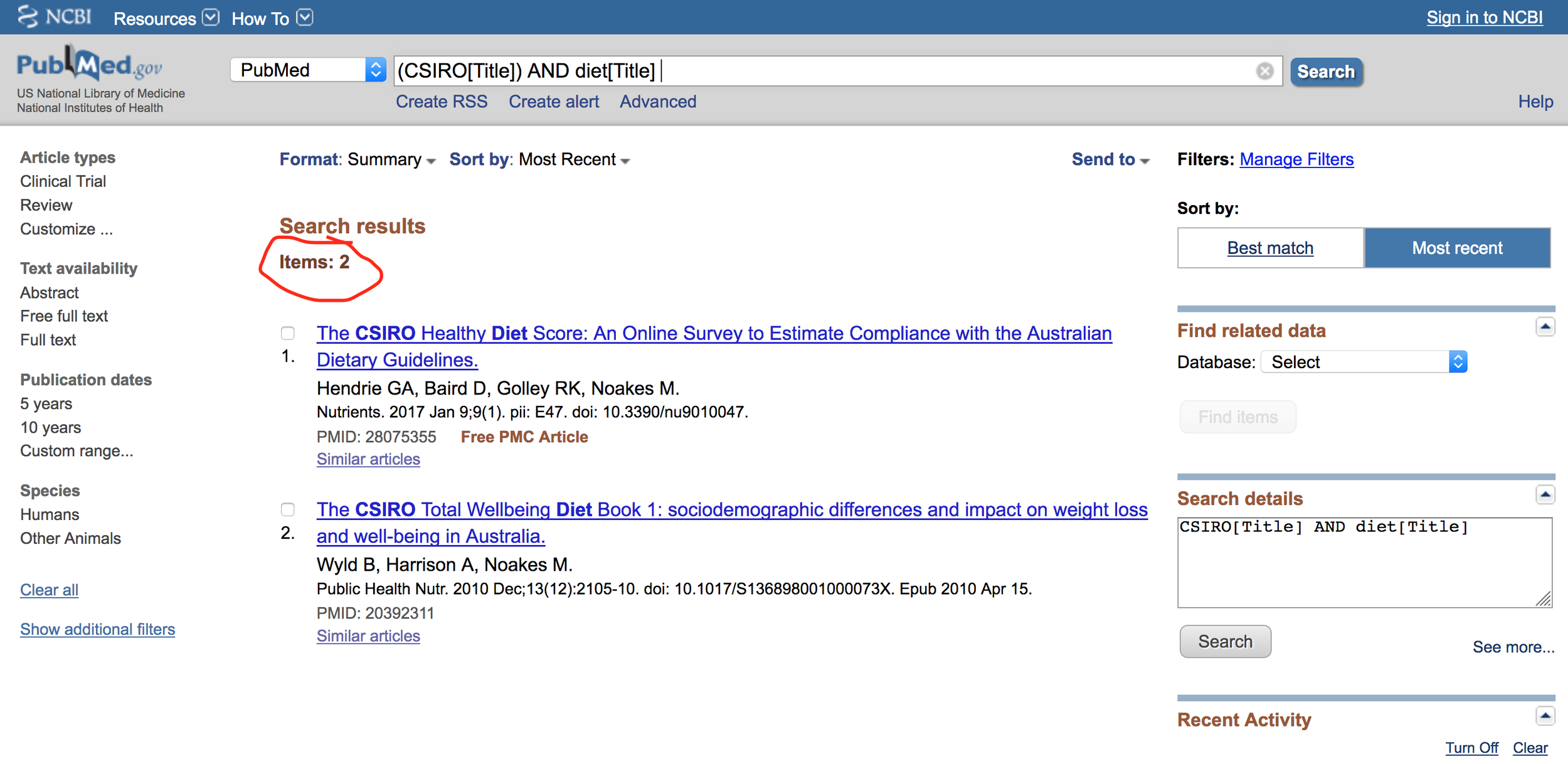

You can see that the DAA doesn’t have a particularly favorable opinion of Paleolithic nutrition by viewing their assessment of the diet on their website. In their opening remarks, they state, “There is debate whether the Paleo Diet is truly healthy or not. Higher-protein diets have been examined in research and a local version has been promoted by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), called the Total Wellbeing Diet[i]. However, compared to the Paleo Diet, the CSIRO Total Wellbeing Diet has been extensively studied in a variety of groups.” This is a remarkable statement as it is a complete misrepresentation of the facts. As the screen shots below show, a search on the US National Library of Medicine’s website (aka PubMed.gov), for (Paleolithic[Title]) AND Diet[Title] returns 46 results, while a search for (CSIRO[Title]) AND diet[Title] returns only 2!

The DAA wants their audience to think that the Paleolithic diet is a

crazy celebrity fad with little to no research. They do attempt to

address a few research papers in their assessment, but the

interpretation leaves much to be desired and of course they conveniently

ignore the vast body of research that exists today supporting

Paleolithic nutrition.

From what I’ve seen, the DAA are doing everything they can to

discredit the Paleo Diet® and protect their brand irrespective of the

vast majority of the research, showing a benefit of following the

Paleolithic dietary template. Which is actually a great shame, as I

think the DAA is missing out on a wonderful opportunity to help the

Australian populace.

As will be discussed, what the current study does highlight is that

there is clearly confusion as to what actually constitutes a modern

Paleolithic diet. One of the major downsides of Dr. Loren Cordain’s

research going viral and the subsequent creation of the Paleo diet

movement, was the simultaneous creation of many self-determined experts.

They have in turn, created their own versions of a Paleolithic diet

that, and unlike the template created by Dr. Cordain, have not been

supported by the peer-reviewed process. So, it would make sense for the

DAA to include the science and practical implementation of a modern

Paleolithic Diet within their APD program to help with this confusion.

What does all this have to do with the newest research paper on The Paleo Diet from Australia?

Well, first, the research was conducted at Edith Cowan University which has a dietetics education program

accredited by the DAA. On its own, that shouldn’t be a red flag,

however, there are a number of other issues that need to be considered.

First, the research paper, to me, was not written with the impartial

tone that one is used to seeing in research papers. The very opening

statement in the abstract appeared unusual. It stated, “The Paleolithic

diet is promoted worldwide for improved gut health.” This statement

stood out because while I am certainly aware of the benefits both

clinically and from the research, it is a rather specific point given

the relatively limited research related to the adoption of a Paleolithic

diet and its effect on gut health.

If you conduct an advanced search at PubMed.gov using Paleolithic AND

Diet AND Gut AND Health, as of this writing, you will be presented with

just 13 studies that match this search criteria. One of which is this

current study, leaving 12 studies that match the search. One could argue

that seven of these studies could be related to the adoption of a

Paleolithic diet and gut health, which again, seems limited to justify

such a statement.

So, I was interested in seeing why this study used that statement

about the Paleolithic Diet being promoted worldwide for gut health. It

was cited, so I quickly turned the pages to see the source of this front

and center statement, and was shocked to see that the hypothesis of

this research paper was citing a 2016 book, entitled “The complete gut

health cookbook” written by Pete Evans.2 Yes, that’s correct, the same celebrity chef that I referred to above that the DAA has made a common target.

Now, with no disrespect to Pete Evans, finding a book with that title

does not justify a scientific research group stating that the

Paleolithic diet is being promoted worldwide for improved gut health.

But again, on its own, it also doesn’t mean that the research isn’t a

valid topic to be investigated, I think looking at how Paleolithic

nutrition can influence gut health is a great idea, and there is a

significant body of research that shows that the microbiome of hunter

gatherers is far more diverse than industrialized populations and

correlates to the health of the host.3-33

However, it did make me think we need to dig a little deeper here as

to any potential conflicts of interest. In doing so I found it very

interesting to learn that Edith Cowan University banned high fat

proponent and Bring Back the Fat author, Christine Cronau from speaking at the University, saying it did not align with the institute’s “evidence-based approach”.

Following the reference to Pete Evan’s “The complete gut health

cookbook” was the statement, referring to the Paleolithic diet,

“However, it excludes grains and dairy, food groups that form part of

the evidence-based national Australian and international dietary

guidelines.” “Evidence-based”, suggesting that excluding grains and

dairy is not evidence-based.

Well let’s examine this statement a little further. As I have

previously stated in other articles, Dr. Cordain’s book “The Paleo

Answer” references over 900 sources, with only a handful not coming from

peer-reviewed journal articles34. There’s also Dr. Cordain’s

large body of published peer-review research, each with hundreds of

references. So I would say that’s pretty much evidence-based! But how

about the Australian and international dietary guidelines, are they

really evidence-based? Well that’s another story, but thankfully there

is an eye-opening paper published in 2015 in the British Medical Journal

by Nina Teicholz, that tackles that very question.35 I highly recommend you take the time to read it.

Further, while it is correct that the Paleolithic diet excludes

grains and dairy, it also excludes legumes and all processed foods. It

is interesting to see how many people represent these exclusions as a

negative, but when one appreciates the benefit to detriment ratio of

consuming these foods, one quickly understands the net benefit of

elimination.

So before getting into the details of this particular study, let’s

take a quick look at the database of published research on the effects

of adopting a Paleolithic diet. We’ve been keeping track of this since,

somewhat ironically, the landmark aboriginal study by O’Dea that

demonstrated a marked improvement in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism

after a temporary reversion to a traditional lifestyle36. The list of published studies can be seen at our website here.

Earlier research by the same authors actually finds benefits to The Paleo Diet

Of the now, more than 50 published papers looking at Paleolithic

nutrition, only a few, report any negative consequences (one study’s

title indicated a negative result, but the data actually revealed a

positive outcome!). Dr. Angela Genoni is responsible for three

publications reporting negative findings. However, her first published

study37 demonstrated beneficial outcomes of adopting a

Paleolithic diet but subsequent results have been negative, or perhaps

better stated, they have been presented as negative findings.

Consequently, I think it prudent to examine these publications ahead of

her most recent paper. To clarify, in her earlier research only one

study was actually conducted, and the data was presented in three

separate publications.37,38,39

The opening line in the abstract of the first published paper, while

certainly open for interpretation, seems grossly inaccurate, at least to

me. The paper states that “limited literature surrounds the dietary

pattern” and referenced three published papers despite there being

nearly 30 experimental studies at the time of publication (see, again,

our chronological publication list), and many more research publications

that support the Paleolithic nutritional template. This just supports

my concern that the research was not being conducted with impartiality

as it is very easy to use PubMed.org and obtain these studies. And this

of course does not even include the many studies that support the

negative consequences of consuming grains, legumes, dairy and processed

food, foods not included in the Paleo Diet®, listed in Dr. Cordain’s

book, The Paleo Answer.34

In Dr. Genoni’s first study, the dietary intervention is described as

follows: “Those in the Paleolithic group were provided with meal ideas

obtained from “The Paleo Diet” book [Cordain, L. The Paleo Diet;

JohnWiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011.] and advised to

consume lean meats, fish, eggs, nuts, fruits and vegetables, and small

amounts of olive or coconut oils. Grains, cereals and dairy products

were not permitted. Dairy products were replaced with unsweetened almond

milk. Sugarless black coffee and tea were allowed. All vegetables were

permitted on the diet, except for corn, white potatoes and legumes. To

ensure adequate carbohydrate, additional fruit was recommended. Dried

fruit was limited to one tablespoon per day.” I’d say this is a good

recommendation to implement a modern Paleo Diet®, although one should

point out that corn, potatoes and legumes are not vegetables, and there

should be no need to recommend additional fruit.

The study concluded that in healthy females, the Paleolithic diet

induced a more favorable effect on body composition over the short-term

intervention period. The full paper can be accessed here.

The second study, published just a few months after the first

publication, was titled “Compliance, Palatability and Feasibility of

PALEOLITHIC and Australian Guide to Healthy Eating Diets in Healthy

Women: A 4-Week Dietary Intervention”.38 As already stated,

this research was part of the first study examining the cardiovascular

and metabolic impacts of the diets. If you are interested in reading

about the findings, you can get access to the full article here.

I would only like to make one important point. In the discussion, the

authors state, “While both groups viewed the diets as healthy, a

greater proportion of the Paleolithic group felt that the diet did not

fit with the belief of a ‘healthy’ diet. This may reflect participant

belief that while the Paleolithic diet is high in ‘healthy

foods’ such as fruits, vegetables, eggs, meats and nuts, the elimination

of grains and dairy products makes the dietary pattern less healthy or

unhealthy.” Well is this really that surprising given that the DAA is

shouting from the rooftops, that the elimination of dairy and grains is a

really, bad idea!

The third publication presented data on the dietary intake of

resistant starch (RS), a dietary component that has similar

physiological effects as dietary fiber and potentially related to bowel

health, and the serum concentrations of TMAO, a potential biomarker of

CVD.39 The full paper is also available on-line and can be accessed here.

The data showed a significant reduction in RS for the Paleolithic diet

but did not show a significant difference in TMAO between the two diets.

The authors speculated that the inability to see a difference in

TMAO, may have been due to a small sample size and the low total energy

of the diet. However, it should be emphasized that this data is from the

same study that did show the Paleolithic diet to significantly improve

body composition. With respect to RS, increasing RS in typical western

diets may well confer a benefit, because of the low fiber intake,

however, when total dietary fiber intake is high, which it is on a

Paleolithic diet (confirmed by the groups own research37), increasing RS likely has little benefit.

The most recent study by this group fundamentally changes their study design

Because the initial study only examined the effect of a Paleolithic

diet over a short-term, 4-week intervention, the current study was

designed to see if long-term adherence to a Paleolithic diet, compared

to controls, would also see a significant reduction in RS and an

increase in TMAO. Recruitment for the study was done via online

advertisements.

Unlike the initial research where no increase in TMAO was seen, the

data from this study did show an increase, as well as a reduction in RS.

However, TMAO is a complicated topic and we will be addressing this in a

detailed follow-up article in the future. But suffice to say, one

cannot state that increased TMAO concentrations is causative of CVD,

rather there has only been shown a correlation between high TMAO levels

and CVD.

While the current study has shown an increase in TMAO, this does not

match the findings of many previous studies already referenced that have

shown a Paleolithic Diet to decrease markers of CVD. And correlation is

not causation. Further there is a difference between exogenous TMAO

from foods, primarily fish and red meat, and endogenous TMAO produced by

microorganisms in the gut. To highlight this point, fish is one of the

greatest dietary sources of TMAO40 and yet, fish has been well established as being cardio-protective.41

So, while fish can elevate TMAO but not be the cause of CVD, CVD could

certainly be responsible for increasing TMAO, two very different

physiological outcomes.

But of major concern with the current study is its design. The

authors categorized Strict Paleolithic (SP) as subjects that consumed

<1 serving of grains and dairy per day and Pseudo-Paleolithic (PP) as

subjects that consumed >1 serving of grains and dairy per day. I

think a more appropriate categorization would be SP as having <1-2

servings of grains and dairy per week and PP having <1 serving of

grains and dairy per day, and even that might be a stretch (no data was

presented with respect to legume consumption in the present study,

although the first study did, and consumption was minimal).

So, the big question to ask here is: did the subjects assigned to

the respective Paleolithic diets even consume a Paleolithic diet? My

colleague on the Paleo Diet® Team, Trevor Connor, has also written an article

about this study and shared the same concern with me regarding this

question. So Trevor compared the reported dietary data and shows it in a

table in his article. What it confirms is that the current study did

not examine a Paleolithic diet compared to the template developed by Dr.

Cordain, particularly when one compares the dietary fiber.

Interestingly, when one looks at the fiber content of their initial

study, as a percentage of caloric intake, the fiber content matches up

very closely to the Paleolithic diet presented by Dr. Cordain in his

2002 paper.42 And this initial study showed the Paleolithic diet to improve body composition while not increasing TMAO.

So, in summary, since the current research paper didn’t actually

examine a Paleolithic diet, the conclusion cannot be made that the

Paleolithic diet raises serum TMAO. However, earlier research conducted

by Genoni et al., when an appropriate Paleolithic diet was administered,

did demonstrate a Paleolithic diet to improve body composition in a

4-week intervention, without increasing TMAO. Perhaps the most important

finding of this study, is that there are many people thinking they are

following a Paleolithic diet when they are not doing so, which

highlights the importance of from where individuals are obtaining their

information!

References

1. Genoni, A., et al., Long-term Paleolithic diet is associated

with lower resistant starch intake, different gut microbiota composition

and increased serum TMAO concentrations. Eur J Nutr. 2019 Jul 5. doi: 10.1007/s00394-019-02036-y.

2. Evans, P., The complete gut health cookbook. 2016, Sydney: Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Ltd.

3. Cockburn, T.A., Infectious diseases in ancient populations. Curr Anthropol, 1971. 12: p. 45-62.

4. Nasidze, I., et al., High Diversity of the Saliva Microbiome in Batwa Pygmies. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e23352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023352. Epub 2011 Aug 16.

5. Bengmark, S. Nutrition of the Critically Ill—A 21st-Century Perspective Nutrients. 2013 Jan 14;5(1):162-207. doi: 10.3390/nu5010162.

6. Bengmark, S. Nutrition of the critically ill – emphasis on liver and pancreas. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2012 Dec;1(1):25-52. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3881.2012.10.14. Review.

7. Adler, C.J., et al., Sequencing ancient calcified dental

plaque shows changes in oral microbiota with dietary shifts of the

Neolithic and Industrial revolutions. Nat Genet. 2013 Apr;45(4):450-5, 455e1. doi: 10.1038/ng.2536. Epub 2013 Feb 17.

7. London, D. and Hruschka, D., Helminths and human ancestral immune ecology: What is the evidence for high helminth loads among foragers? Am J Hum Biol, 2014. 26(2): p. 124-9.

8. Martinez, F.D., The Human Microbiome Early Life Determinant of Health Outcomes Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014 Jan;11 Suppl 1:S7-12. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201306-186MG.

9. Quercia, S., et al., From lifetime to evolution: timescales of human gut microbiota adaptation. Front Microbiol. 2014 Nov 4;5:587. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00587. eCollection 2014.

10. Rook, G.A., Microbial ‘old friends’, immunoregulation and socioeconomic status Clin Exp Immunol. 2014 Jul;177(1):1-12. doi: 10.1111/cei.12269. Review.

11. Schnorr, S.L., Gut microbiome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers. Nat Commun. 2014 Apr 15;5:3654. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4654.

12. Bligh, H.F., Plant-rich mixed meals based on Palaeolithic

diet principles have a dramatic impact on incretin, peptide YY and

satiety response, but show little effect on glucose and insulin

homeostasis: an acute-effects randomised study. Br J Nutr. 2015 Feb 28;113(4):574-84. doi: 10.1017/S0007114514004012. Epub 2015 Feb 9.

13. Logan, A.C., et al., Natural environments, ancestral diets, andmicrobial ecology: is there a modern “paleo-deficit disorder”? Part I J Physiol Anthropol. 2015 Jan 31;34:1. doi: 10.1186/s40101-015-0041-y. Review.

14. Logan, A.C., et al., Natural environments, ancestral diets, andmicrobial ecology: is there a modern “paleo-deficit disorder”? Part I J Physiol Anthropol. 2015 Mar 10;34:9. doi: 10.1186/s40101-014-0040-4. Review.

15. Obregon-Tito, A.J., et al., Subsistence strategies in traditional societies distinguish gut microbiomes. Nat Commun. 2015 Mar 25;6:6505. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7505.

16. Rampelli, S., et al., Metagenome Sequencing of the Hadza Hunter-Gatherer Gut Microbiota. Curr Biol, 2015. 25(13): p. 1682-93.

17. Segata, N., Gut Microbiome: Westernization and the Disappearance of Intestinal Diversity. Curr Biol. 2015 Jul 20;25(14):R611-3. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.05.040.

18. Gomez, A., et al., Gut Microbiome of Coexisting BaAka Pygmies and Bantu Reflects Gradients of Traditional Subsistence Patterns. Cell Rep. 2016 Mar 8;14(9):2142-2153. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.02.013. Epub 2016 Feb 25.

19. Turroni, S., et al., Fecal metabolome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers: a hostmicrobiome integrative view. Sci Rep. 2016 Sep 14;6:32826. doi: 10.1038/srep32826.

20. Turroni, S., et al., Enterocyte-Associated Microbiome of the Hadza Hunter-Gatherers. Front Microbiol. 2016 Jun 6;7:865. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00865. eCollection 2016.

21. Crittenden, A.N. and S.L. Schnorr, Current views on hunter-gatherer nutrition and the evolution of the human diet. Am J Phys Anthropol, 2017. 162 Suppl 63: p. 84-109.

22. Gupta, V.K., et al., Geography, Ethnicity or Subsistence-Specific Variations in Human Microbiome Composition and Diversity. Front Microbiol. 2017 Jun 23;8:1162. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2017.01162. eCollection 2017.

23. Konijeti, G.G., et al., Efficacy of the Autoimmune Protocol Diet for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017 Nov;23(11):2054-2060.

24. Mancabelli, L., et al., Meta-analysis of the human gut microbiome from urbanized and pre-agricultural populations. Environ Microbiol, 2017. 19(4): p. 1379-1390.

25. Rampelli, S., et al., Characterization of the human DNA gut virome across populations with different subsistence strategies and geographical origin. Environ Microbiol. 2017, Nov; 19(11): 4728-4735.

26. Smits, S.A., et al., Seasonal Cycling in the Gut Microbiome of the Hadza Hunter-Gatherers of Tanzania. Science. 2017 Aug 25;357(6353):802-806. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4834.

27. Gentile C.L. and Weir T.L., The gut microbiota at the intersection of diet and human health. Science. 2018 Nov 16;362(6416):776-780. doi: 10.1126/science.aau5812. Review.

28. Jha, A.R., et al., Gut microbiome transition across a lifestyle gradient in Himalaya. PLoS Biol. 2018 Nov 15;16(11):e2005396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2005396. eCollection 2018 Nov.

29. Lassalle, F., et al., Oral microbiomes from hunter-gatherers

and traditional farmers reveal shifts in commensal balance and pathogen

load linked to diet. Mol Ecol. 2018 Jan;27(1):182-195.

30. Valle Gottlieb, M.G., et al., Impact of human aging and modern lifestyle on gut microbiota. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2018 Jun 13;58(9):1557-1564.

31. Ganguli, S., et al., Gut microbial dataset of a foraging

tribe from rural West Bengal – insights into unadulterated and

transitional microbial abundance. Data Brief. 2019 May 24;25:103963. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2019.103963. eCollection 2019 Aug.

32. Hansem, M.E.B., et al., Population structure of human gut bacteria in a diverse cohort from rural Tanzania and Botswana. Genome Biol. 2019 Jan 22;20(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1616-9.

33. Fragiadakis, G.K., et al., Links between environment, diet, and the hunter-gatherer microbiome. Gut Microbes, 2019. 10(2): p. 216-227.

34. Cordain, L., The Paleo Answer. 2012, Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley.

35. Teicholz, N., The scientific report guiding the US dietary guidelines: is it scientific? BMJ 2015;351:h4962 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4962 (Published 23 September 2015).

36. O’Dea K: Marked improvement in carbohydrate and lipid

metabolism in diabetic Australian aborigines after temporary reversion

to traditional lifestyle. Diabetes 1984, 33(6):596-603.

37. Genoni, A. et al., Cardiovascular, Metabolic Effects and

Dietary Composition of Ad-Libitum Paleolithic vs. Australian Guide to

Healthy Eating Diets: A 4-Week Randomised Trial. Nutrients 2016, 8, 314; doi:10.3390/nu8050314.

38. Genoni, A. et al., Compliance, Palatability and Feasibility

of PALEOLITHIC and Australian Guide to Healthy Eating Diets in Healthy

Women: A 4-Week Dietary Intervention. Nutrients. 2016 Aug 6;8(8).

39. Genoni, A. et al., A Paleolithic diet lowers resistant starch

intake but does not affect serum trimethylamine-N-oxide concentrations

in healthy women. Br J Nutr. 2019 Feb;121(3):322-329.

40. Kruger et al., Associations of current diet with plasma and urine TMAO in the KarMeN study: direct and indirect contributions. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017 Nov;61(11).

41. Kwok, C.S., et al., Dietary components and risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: a review of evidence from meta-analyses. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019 Apr 11:2047487319843667. doi: 10.1177/2047487319843667. [Epub ahead of print]

42. Cordain, L., The nutritional characteristics of a contemporary diet based upon Paleolithic food groups. Journal of the American Nutraceutical Association, 2002. 5(5): p. 15-24.

blocks7copy1}