Wheat Series Part 2: Wheat and Gluten’s Effect on Intestinal Permeability

It was a comment I’d heard too many times. I was watching tennis with a friend who knew me as a cyclist, not as someone who researches nutrition. The commentators were discussing world number-one ranked tennis player Novak Djokovic’s newfound success since going on a gluten-free diet. My friend got noticeably irritated and finally blurted, “I’m tired of this gluten-free fad! There’s not a scrap of evidence it makes a difference unless you have celiac disease.”

As much as I wanted to, I chose not to respond, but thought to myself, The bottom drawer of my research cabinet is awfully heavy for not having a scrap of anything in it. This viewpoint that the health benefits of a gluten-free diet are more fad than science is a pervasive one. But what has led so many—including doctors and scientists—to say the research doesn’t exist?

Certainly the science is extensive for celiac disease where the role of gluten is indisputable. Gliadin, a protein in gluten, binds to a molecule in our bodies called tissue transglutaminase. In celiac patients it’s this new, combined molecule that sets off the inappropriate immune response.1, 2, 3 Without gluten, celiac disease couldn’t exist.

Recently other gluten-related disorders like gluten allergies and gluten ataxia have been identified.4, 5 But admittedly, these conditions affect only about 2-10% of the population. Outside of these diseases my friend has a point: research showing gluten having a direct pathogenic role, as it does in celiac disease, isn’t there.

But perhaps this is where the disconnect exists.

While a great deal of published research is showing that wheat and gluten can promote a large range of chronic conditions,4, 6, 7, 8 gluten’s role is not so direct. Instead, gluten may break down the body’s natural defenses, setting up an inflammatory environment. This environment is highly conducive to a variety of chronic diseases in those of us who are unfortunate enough to have the wrong genetics.9, 10

Gluten is just one of the ways in which wheat can set the stage for unwanted inflammation and disease. Let’s start with a surprising function that came out of celiac research.

Zonulin and Its Triggers

One of the most important roles of our gut, beside processing nutrients and hosting rich microflora, is to provide a barrier blocking the entry of unwanted particles into the bloodstream. Fortunately tight junctions (TJ) between the epithelial cells of our intestine carefully regulate entry of all but a few small molecules and essential nutrients.

Over the last 20 years, Dr. Alessio Fasano at the University of Maryland has researched breakdowns in this barrier, ultimately identifying a molecule produced in the gut called zonulin.14 Zonulin has the unique ability to dissolve the occludins, claudins, zonular occluden, and ZO-1 proteins that make up the structural cytoskeletons of our tight junctions.6, 15, 16, 17, 18

Put simply, zonulin can breakdown our intestinal barrier and increase permeability. An effect that’s often referred to around the web as “leaky gut.” It is rapid, reproducible, and—fortunately—reversible.16

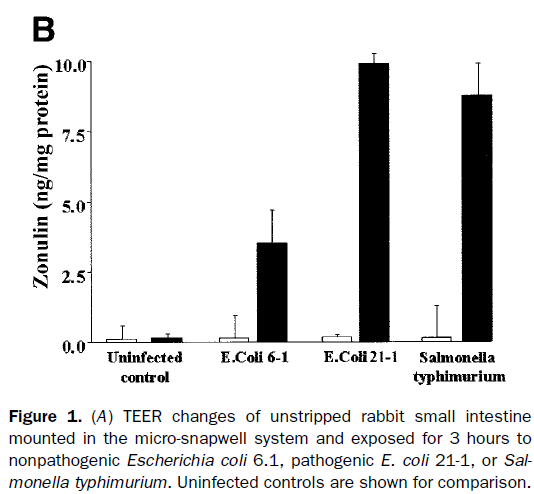

To date, two powerful triggers for zonulin have been identified. The first trigger is exposure to bacteria in the intestine. Interestingly, infection by both pathogenic and “healthy” bacteria can have a triggering effect. However, it’s amplified with the “bad guys” as we can see from the chart below.19

It is believed that zonulin evolved to protect us against bacterial colonization in the gut.6, 17, 19 When there’s an overload of bacteria in an otherwise healthy digestive tract, zonulin opens up the tight junctions allowing fluid to rush into the gut and flush out microorganisms.

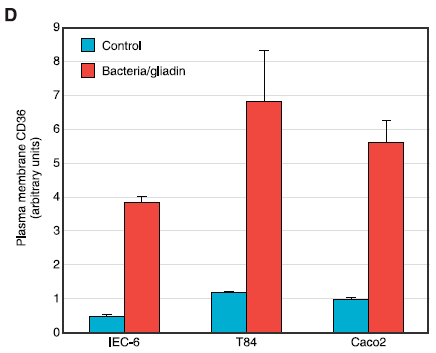

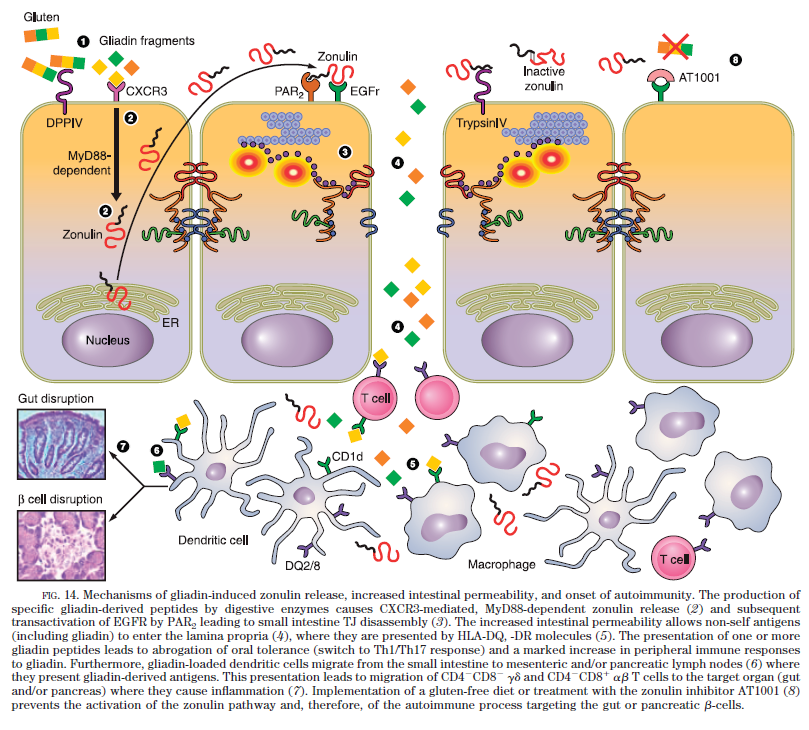

The second powerful activator of the zonulin system is gliadin. Gliadin fragments bind to the CXCR3 receptor on the epithelial cells of the gut. Then through a MyD88 signaling process, these epithelial cells release zonulin and cause an opening of tight junctions.6, 15, 17, 20, 21

It’s a complex process, but all you need to know is that gliadin can do this from inside the gut. It doesn’t have to get into our systems. More importantly, gluten is inappropriately hijacking a powerful defense mechanism designed to handle bacterial contamination.17

In the above figure, we can see from Dr. Fasano’s research how gliadin’s ability to stimulate zonulin can be as powerful as bacterial triggers.6

Finally, while gliadin’s effect is much stronger in individuals with celiac disease, gliadin does not discriminate, and it happens in all people’s guts.6, 17

Consequences of Intestinal Permeability

With a healthy gut barrier, large molecules are degraded before entering the body and are well tolerated by the immune system.12 Intestinal permeability caused by gluten and bacteria allows these large molecules to get into circulation and act as antigens (activators) for the immune system.15, 17, 22

This becomes a real concern considering gluten is normally consumed with a meal. Its rapid effect on gut permeability happens at the same time that the gut is being hit by a large number of foreign antigens.

Dr. Fasano and his group proposed that once these antigens gain entry, they can be misinterpreted by the immune system in genetically susceptible individuals. The result is an inappropriate immune response that ultimately leads to chronic illness.6, 12, 15, 23, 24, 25 In a healthy gut, these antigens would never gain access to the immune system.

The image below provides a representation of how gluten can open tight junctions and lead to diseases such as celiac disease and type 1 diabetes.6

Losing the Barrier to Disease

So, what does this all amount to? Intestinal permeability caused by either bacterial overgrowth or gluten (both of which are heavily influenced by diet) may be a key early step to set the body up for many chronic illnesses.

But is there any research? Fortunately, this is where I have to start using more drawers in my research cabinet.

Higher zonulin levels and intestinal permeability have been associated with and often precede many autoimmune conditions including celiac disease,17, 28, 34 multiple sclerosis,35, 36 rheumatoid arthritis,37, 38 ankylosing spondylitis,37, 39 and Crohn’s disease.40, 41 Eating wheat has been directly linked to diabetes.16, 30, 31, 32, 33, 42, 43, 44

A popular theory of autoimmune disease called the molecular mimicry theory proposed that autoimmune disease is initiated by viruses that mimic our bodies.26, 27 Dr. Fasano and his group suggested instead that dietary antigens passing through a leaky gut may be the environmental trigger. To test their theory, they were able to use a zonulin inhibitor to reduce the severity of celiac disease symptoms in humans28 and the incidence of type 1 diabetes in mice.29

Intestinal permeability isn’t just associated with autoimmune conditions. Permeability may affect asthmatics by increasing their exposure to allergens.45, 46 Elevated zonulin levels have been found in inflammatory bowel disease 47, 48 and cancer.49, 50 Even schizophrenia has recently been linked to gluten consumption and zonulin levels.51, 52 But a final question remains.

In a world where most people reach for a bagel and toast as soon as they get out of bed, intestinal permeability may just be a part of Western life that gets an unfair rap by association. In other words, is it too easy to just link permeability with chronic disease? Does it really play a role?

In his 2011 review of zonulin and disease, Dr. Fasano addressed this question, pointing out a number of studies where symptoms and incidence rates were reduced when gluten was removed from the diet or when zonulin’s effects were blocked.6 Wheat, a no-no for any good Paleo dieter, was clearly opening doors.

Explore the rest of our Wheat Series:

Part 1: The Digestive Immune System

NEXT: How Wheat Mimics Bacteria

Part 4: Wheat as a Harmful Dietary Antigen

Part 5: How Wheat Can Trigger Chronic Disease

References

[1]Dieterich, W., et al., Identification of tissue transglutaminase as the autoantigen of celiac disease. Nature Medicine, 1997. 3(7): p. 797-801.

[2]Molberg, O., et al., Tissue transglutaminase selectively modifies gliadin peptides that are recognized by gut-derived T cells in celiac disease. Nature Medicine, 1998. 4(6): p. 713-717.

[3]Plenge, R.M., Unlocking the pathogenesis of celiac disease. Nat Genet, 2010. 42(4): p. 281-2.

[4]Sapone, A., et al., Spectrum of gluten-related disorders: consensus on new nomenclature and classification. BMC Med, 2012. 10: p. 13.

[5]Hadjivassiliou, M., et al., Gluten ataxia in perspective: epidemiology, genetic susceptibility and clinical characteristics. Brain, 2003. 126(Pt 3): p. 685-91.

[6]Fasano, A., Zonulin and its regulation of intestinal barrier function: the biological door to inflammation, autoimmunity, and cancer. Physiol Rev, 2011. 91(1): p. 151-75.

[7]Biesiekierski, J.R., et al., Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without celiac disease: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol, 2011. 106(3): p. 508-14; quiz 515.

[8]Bernardo, D., et al., Is gliadin really safe for non-coeliac individuals? Production of interleukin 15 in biopsy culture from non-coeliac individuals challenged with gliadin peptides. Gut, 2007. 56(6): p. 889-890.

[9]Palova-Jelinkova, L., et al., Gliadin fragments induce phenotypic and functional maturation of human dendritic cells. J Immunol, 2005. 175(10): p. 7038-45.

[10]De Palma, G., et al., Effects of a gluten-free diet on gut microbiota and immune function in healthy adult human subjects. Br J Nutr, 2009. 102(8): p. 1154-60.

[11]Yu, Q.H. and Q. Yang, Diversity of tight junctions (TJs) between gastrointestinal epithelial cells and their function in maintaining the mucosal barrier. Cell Biol Int, 2009. 33(1): p. 78-82.

[12]Fasano, A., Physiological, Pathological, and Therapeutic Implications of Zonulin-Mediated Intestinal Barrier Modulation Living Life on the Edge of the Wall. American Journal of Pathology, 2008. 173(5): p. 1243-1252.

[13]Shen, L. and J.R. Turner, Role of epithelial cells in initiation and propagation of intestinal inflammation. Eliminating the static: tight junction dynamics exposed. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 2006. 290(4): p. G577-82.

[14]Di Pierro, M., et al., Zonula occludens toxin structure-function analysis. Identification of the fragment biologically active on tight junctions and of the zonulin receptor binding domain. J Biol Chem, 2001. 276(22): p. 19160-5.

[15]Sander, G.R., et al., Rapid disruption of intestinal barrier function by gliadin involves altered expression of apical junctional proteins. FEBS Lett, 2005. 579(21): p. 4851-5.

[16]Visser, J., et al., Tight junctions, intestinal permeability, and autoimmunity: celiac disease and type 1 diabetes paradigms. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2009. 1165: p. 195-205.

[17]Drago, S., et al., Gliadin, zonulin and gut permeability: Effects on celiac and non-celiac intestinal mucosa and intestinal cell lines. Scand J Gastroenterol, 2006. 41(4): p. 408-19.

[18]Fasano, A., et al., Zonula occludens toxin modulates tight junctions through protein kinase C-dependent actin reorganization, in vitro. J Clin Invest, 1995. 96(2): p. 710-20.

[19]El Asmar, R., et al., Host-dependent zonulin secretion causes the impairment of the small intestine barrier function after bacterial exposure. Gastroenterology, 2002. 123(5): p. 1607-15.

[20]Lammers, K.M., et al., Gliadin induces an increase in intestinal permeability and zonulin release by binding to the chemokine receptor CXCR3. Gastroenterology, 2008. 135(1): p. 194-204 e3.

[21]Clemente, M.G., et al., Early effects of gliadin on enterocyte intracellular signalling involved in intestinal barrier function. Gut, 2003. 52(2): p. 218-23.

[22]Fasano, A., Intestinal zonulin: open sesame! Gut, 2001. 49(2): p. 159-62.

[23]Cereijido, M., et al., New diseases derived or associated with the tight junction. Arch Med Res, 2007. 38(5): p. 465-78.

[23]Fasano, A., Surprises from celiac disease. Sci Am, 2009. 301(2): p. 54-61.

[24]Mowat, A.M., Anatomical basis of tolerance and immunity to intestinal antigens. Nat Rev Immunol, 2003. 3(4): p. 331-41.

[25]Oldstone, M.B.A., MOLECULAR MIMICRY AND AUTOIMMUNE-DISEASE. Cell, 1987. 50(6): p. 819-820.

[26]Wucherpfennig, K.W. and J.L. Strominger, MOLECULAR MIMICRY IN T-CELL-MEDIATED AUTOIMMUNITY – VIRAL PEPTIDES ACTIVATE HUMAN T-CELL CLONES SPECIFIC FOR MYELIN BASIC-PROTEIN. Cell, 1995. 80(5): p. 695-705.

[27]Paterson, B.M., et al., The safety, tolerance, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects of single doses of AT-1001 in coeliac disease subjects: a proof of concept study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2007. 26(5): p. 757-66.

[28]Watts, T., et al., Role of the intestinal tight junction modulator zonulin in the pathogenesis of type I diabetes in BB diabetic-prone rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2005. 102(8): p. 2916-21.

[29]Bosi, E., et al., Increased intestinal permeability precedes clinical onset of type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia, 2006. 49(12): p. 2824-7.

[30]Mojibian, M., et al., Diabetes-specific HLA-DR-restricted proinflammatory T-cell response to wheat polypeptides in tissue transglutaminase antibody-negative patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes, 2009. 58(8): p. 1789-96.

[31]Sapone, A., et al., Zonulin upregulation is associated with increased gut permeability in subjects with type 1 diabetes and their relatives. Diabetes, 2006. 55(5): p. 1443-1449.

[32]De Magistris, L., et al., Altered mannitol absorption in diabetic children. Ital J Gastroenterol, 1996. 28(6): p. 367.

[33]De Palma, G., et al., Intestinal dysbiosis and reduced immunoglobulin-coated bacteria associated with coeliac disease in children. BMC Microbiol, 2010. 10: p. 63.

[34]Westall, F.C., Abnormal hormonal control of gut hydrolytic enzymes causes autoimmune attack on the CNS by production of immune-mimic and adjuvant molecules: A comprehensive explanation for the induction of multiple sclerosis. Med Hypotheses, 2007. 68(2): p. 364-9.

[35]Yacyshyn, B., et al., Multiple sclerosis patients have peripheral blood CD45RO+ B cells and increased intestinal permeability. Dig Dis Sci, 1996. 41(12): p. 2493-8.

[36]Smith, M.D., R.A. Gibson, and P.M. Brooks, Abnormal bowel permeability in ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol, 1985. 12(2): p. 299-305.

[37]Edwards, C.J., Commensal gut bacteria and the etiopathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol, 2008. 35(8): p. 1477-14797.

[38]Liu, J., et al., Identification of disease-associated proteins by proteomic approach in ankylosing spondylitis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2007. 357(2): p. 531-6.

[39]D’Inca, R., et al., Increased intestinal permeability and NOD2 variants in familial and sporadic Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2006. 23(10): p. 1455-61.

[40]Irvine, E.J. and J.K. Marshall, Increased intestinal permeability precedes the onset of Crohn’s disease in a subject with familial risk. Gastroenterology, 2000. 119(6): p. 1740-4.

[41]Maurano, F., et al., Small intestinal enteropathy in non-obese diabetic mice fed a diet containing wheat. Diabetologia, 2005. 48(5): p. 931-7.

[42]Ziegler, A.G., et al., Early infant feeding and risk of developing type 1 diabetes-associated autoantibodies. JAMA, 2003. 290(13): p. 1721-8.

[43]Funda, D.P., et al., Gluten-free but also gluten-enriched (gluten+) diet prevent diabetes in NOD mice; the gluten enigma in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes-Metabolism Research and Reviews, 2008. 24(1): p. 59-63.

[44]Knutson, T.W., et al., Effects of luminal antigen on intestinal albumin and hyaluronan permeability and ion transport in atopic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 1996. 97(6): p. 1225-32.

[45]Hijazi, Z., et al., Intestinal permeability is increased in bronchial asthma. Arch Dis Child, 2004. 89(3): p. 227-9.

[46]Arrieta, M.C., et al., Reducing small intestinal permeability attenuates colitis in the IL10 gene-deficient mouse. Gut, 2009. 58(1): p. 41-8.

[47]Weber, C.R. and J.R. Turner, Inflammatory bowel disease: is it really just another break in the wall? Gut, 2007. 56(1): p. 6-8.

[48]Lai, C.H., et al., Proteomics-based identification of haptoglobin as a novel plasma biomarker in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Chim Acta, 2010. 411(13-14): p. 984-91.

[50]Dowling, P., et al., 2-D difference gel electrophoresis of the lung squamous cell carcinoma versus normal sera demonstrates consistent alterations in the levels of ten specific proteins. Electrophoresis, 2007. 28(23): p. 4302-10.

[51]Wan, C., et al., Abnormal changes of plasma acute phase proteins in schizophrenia and the relation between schizophrenia and haptoglobin (Hp) gene. Amino Acids, 2007. 32(1): p. 101-8.

[52]Kalaydjian, A.E., et al., The gluten connection: the association between schizophrenia and celiac disease. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 2006. 113(2): p. 82-90.