Inflammatory Bowel Disorders: Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis According to the Mismatch Hypothesis (part 2)

In part 1 of our series on inflammatory bowel disorders (IBD), we introduced the grouping term for ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), currently affecting 1 in 117 Americans.

IBD is considered chronic and progressive. This was also thought to be the case with type 2 diabetes, until the emergence of recent evidence showing it can be reversed in many people if they follow a well-formulated, carbohydrate-restricted diet. [1]

The hope is for similar advancements with respect to IBD research and treatment, whether through diet, drug, microbe, or a combination of interventions.

In part 2, we explore the official guidelines for treating IBD and how successful they are at helping patients avoid surgery. Then, we discuss the (sometimes randomized) clinical trials. We also review the non-pharmaceutical interventions such as diet. Finally, we look at future areas of research.

IBD Guideline Treatments

IBD has a remitting and relapsing nature. In CD, for instance, “approximately half of all the patients will be [in] clinical remission. If an individual patient is in remission for one year, there is an 80 percent chance [that] this individual will remain in remission in the subsequent year.” [2]

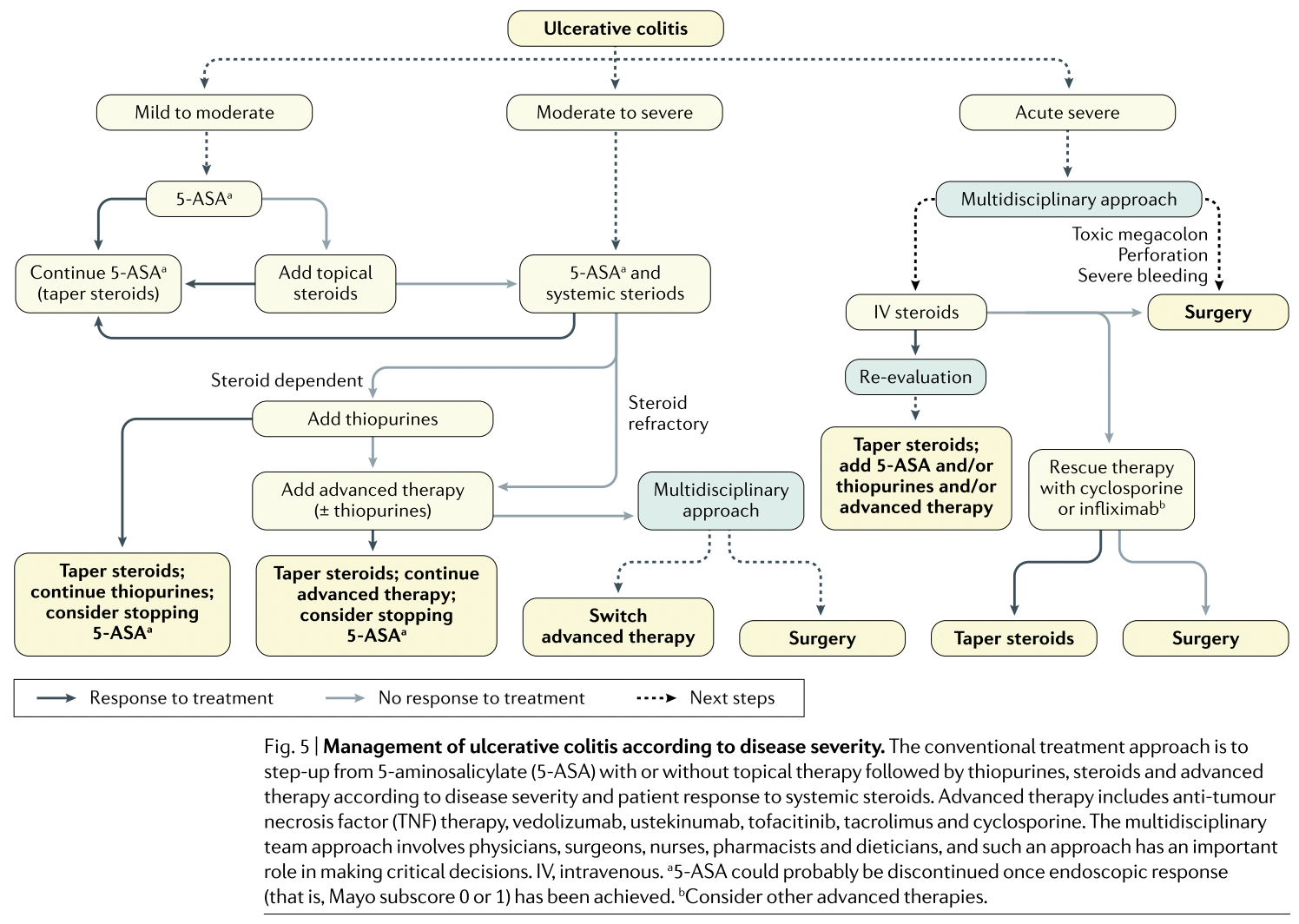

Gastroenterologists manage IBD with four classes of medications:

- Anti-inflammatories like 5-aminosalicylic acid (5ASA)

- Antibiotics like ciprofloxacin or metronidazole

- Steroids like prednisone

- Immunosuppressants like methotrexate or TNFɑ inhibitors

These medications aren’t designed to address root cause issues but may lessen flare-ups and even delay the need for surgery. Below is a typical treatment algorithm for UC—which is similar in several ways to CD—which rotates patients between these drugs at various doses. [3]

5ASA is the most common anti-inflammatory drug used as a first-line treatment for ulcerative colitis. Randomized-controlled trials (RCTs) suggest 29 percent of people can expect remission with 5ASA compared to 17 percent in the placebo group. [4]

RCTs looking at immunosuppressants (or modulators) like azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine (6MP) in CD don’t appear to perform any better than placebo, all the while producing serious side-effects. [5]

Thus, the overall picture is mixed. The landscape for IBD patients isn’t particularly encouraging. Most drugs have a modest benefit while others have none at all, with side-effects ranging from modest (e.g. 5ASA) to serious (e.g. 6MPT).

There are alternatives to the recommended IBD treatments for patients still seeking the remission of their disease. These interventions tend to be used across a wide spectrum of autoimmune patients, like those with rheumatoid arthritis or Celiac disease. Their side effects tend to be quite minor.

Let’s take a closer look at some of the most promising interventions.

Dietary Interventions to Treat IBDs

IBD patients often turn to diet interventions to complement or even replace the typical recommended treatments, since those guidelines can often fail to provide the expected relief.

Elimination diets are a hot topic among this patient community given the encouraging number of medical case-reports or uncontrolled open-label trials that have shown success. [6,7] This often drives people to learn about and experiment with both Paleo and carnivore diets.

Elimination diets hope to exclude so-called “Neolithic agents” (i.e. those foods that we are poorly adapted to consume), thus “restoring balance of intestinal flora, modulating immune activation, reducing overgrowth of proinflammatory bacteria, and promoting nutrient intake and mucosal healing.” [8]

One such diet called ‘”Low FODMAP” was tested against a standard American diet for six weeks in a randomized-controlled trial. The results suggested it was “safe for patients with IBD [showing] an amelioration of fecal inflammatory markers and quality of life even in patients with mainly quiescent disease.” [9]

FODMAP stands for Fermentable Oligo- Di- Mono-saccharides And Polyols. In simple terms, it eliminates mostly plant fiber. In practice, people reduce or eliminate their intake of fruit, nuts, and vegetables, especially the high-fiber ones. Milk and dairy contain disaccharides and are thus commonly eliminated as well.

Despite the drug-centric guidelines, dietary interventions are sometimes prescribed as follows [10]:

- A low-residue diet eliminating nuts, seeds, whole grains, corn hulls, and raw fruit, especially with their peel, and most vegetables (notably cruciferous varieties)

- Lactose-free diets eliminating natural milk

- Carbohydrate-restricted diets

- Specific carbohydrate diets (SCD) eliminating all complex sugars (lactose, sucrose), starches (corn, rice, and flour), grains and legumes, permitting only monosaccharides (glucose, fructose, and galactose) found in certain kinds of fruit, honey, and yogurts

- Gluten-free diet eliminating all sources of gluten

- Low-FODMAP (see above)

- Exclusive enteral nutrition (EEN) for when the disease gets extremely severe. It’s nutrition shunted straight into your gastrointestinal tract (bypassing your mouth) via a tube, catheter, or stoma

The recurring theme across these various dietary patterns is clear: fewer foods made from plant matter. From an evolutionary standpoint, plants are the major source of dietary toxins and immunogenic compounds in the human diet. [11,12]

It’s not unreasonable to expect that when disease is present, lessening the dietary immunological load may reduce the severity of symptoms.

A small, uncontrolled non-randomized six-week trial saw 73 percent (11 of 15) IBD patients—nine with CD and six with UC—achieve remission with an autoimmune Paleo diet (AIP), eliminating grains, legumes, nightshades, dairy, eggs, coffee, alcohol, nuts, seeds, refined/processed sugars, oils, and food additives. [13]

A placebo-controlled crossover-RCT confirmed the negative impact of FODMAPs on IBD patients [14] as did another randomized-controlled open-label trial. [15]

Despite these results, many still worry about meat consumption, even (traditionally) processed deli meat like salami. However, a retrospective look at the FACES trial found that “among patients with CD in remission, the level of red and processed meat consumption was not associated with time to symptomatic relapse.” [16]

This lends credence to the mismatch perspective, that those dietary compounds we are poorly adapted to may cause and/or exacerbate IBD (i.e. cereals), not those we’re well adapted to (i.e. red meat).

One would predict that different plants would impact IBD patients differently. Such is the case: “The risk reduction was greatest for fiber derived from fruits, but no beneficial effect was observed with fiber from cereal, whole grains, or legumes.” [17]

The foods that were least present (or not present at all) during our evolution are also those we’re least adapted to—especially in an immunological sense.

There is strong evidence that elimination diets and especially low-carbohydrate ones like the Low-FODMAP diet are effective in IBD treatment, with negligible side-effects compared to relevant pharmaceuticals.

Promising Research Findings

Fecal microbiota transplants (FMTs) show promise as another IBD treatment alternative, but the quality of the data is poor. It’s encouraging, though, that FMTs appear to engender relatively few, and rarely serious, adverse events.

The same can be said of whipworms and probiotic interventions, and those have a higher quality context of evidence. Let’s take a closer look at these data.

One non-randomized, open-label uncontrolled trial on the probiotic product VSL#3 by Sigma Tau Pharmaceuticals, saw remission/response rates of 77 percent with an intent-to-treat analysis. No adverse events were apparent other than mild bloating. [18]

A multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled parallel trial was done for VSL#3 in patients with mild-to-moderate UC, showing improvements of the disease activity index by ≥50% in more people (25) than the placebo group (7) [19]. There was a 42.9% remission rate with VSL#3 in another RCT compared to 15.7% in the placebo group [20].

FMTs were tested on 30 patients in a prospective uncontrolled study. 43.3 percent of them with refractory UC reached clinical, endoscopic, and laboratory remission. 26.7 percent achieved a clinical response at the end of three months following the FMT. [21] In terms of cost and logistical simplicity, it is encouraging for this intervention that “no significant difference existed among overall donor groups in terms of FMT success rate.”

In another study, the whipworm trichuris suis was given over three months in a RCT. 13 of 30 patients (43.3 percent) receiving trichuris suis ova and 4 of 24 (16.7 percent) given placebos improved their disease activity index significantly (≥4), without any side effects. [22]

The hygiene hypothesis suggests that an excess of hygiene deprives us of the crucial exposures to bacteria, viruses and parasites that train our immune system, most often during the childhood developmental phase. The promising results seen from administering select bacteria, screened fecal matter, or whipworms lend support to the hygiene hypothesis.

FMTs, certain probiotics, and whipworms may offer better treatments for IBD than pharmaceuticals, given their mechanisms of action. That is, they are less focused on symptoms and more on the upstream immunomodulatory phenomena.

Conclusion

Currently, no treatment offers a surefire way to put IBD in remission. There are pharmaceutical options with moderate efficacy; but they also come with considerable side effects. Sometimes dietary interventions are prescribed but the most efficacious elimination diets like Paleo and carnivore aren’t endorsed by the vast majority of dietitians and doctors.

It’s not uncommon to see spontaneous remissions. The nutritional status of IBD patients tends to be poor, especially in Crohn’s disease, so ensuring they get enough nutrient-dense animal foods is key.

Standing somewhat in defiance of antibiotics, FMTs, probiotics, and whipworms are emerging as promising treatments targeting immunomodulatory processes rather than symptoms alone. Moreover, their side-effects currently seem quite minor compared to drugs used in the standard of care.

It is important for future IBD-focused research to ensure that low-cost, low-risk, high-reward lifestyle changes are fairly tested, especially interventions relating to vitamin D status and evolutionarily congruent elimination diets.

References

[1] Athinarayanan S, Adams R, Hallberg S, McKenzie A, Bhanpuri N, Campbell W et al. Long-Term Effects of a Novel Continuous Remote Care Intervention Including Nutritional Ketosis for the Management of Type 2 Diabetes: A 2-Year Non-randomized Clinical Trial [Internet]. https://www.frontiersin.org/. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/ar…

[2] Gajendran M, Loganathan P, Catinella A, Hashash J. A comprehensive review and update on Crohn’s disease [Internet]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/…

[3] Kobayashi T, Siegmund B, Le Berre C, Wei S, Ferrante M, Shen B et al. Ulcerative colitis [Internet]. www.nature.com. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.nature.com/article…

[4] Murray A, Nguyen T, Parker C, Feagan B, MacDonald J. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis [Internet]. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.cochranelibrary.co…

[5] Gajendran M, Loganathan P, Catinella A, Hashash J. A comprehensive review and update on Crohn’s disease [Internet]. Disease-a-Month. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/…

[6] Tóth, Dabóczi, Howard, Miller, Clemens. Crohn’s disease successfully treated with the paleolithic ketogenic diet [Internet]. https://www.researchgate.net. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/p…‘s_disease_successfully_treated_with_the_paleolithic_ketogenic_diet

[7] Gibson P, Shepherd S. Evidence-based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: The FODMAP approach [Internet]. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.co…

[8] Chandrasekaran A, Molparia B, Akhtar E, Wang X, Lewis J, Chang J et al. The Autoimmune Protocol Diet Modifies Intestinal RNA Expression in Inflammatory Bowel Disease [Internet]. https://academic.oup.com/. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/crohn…

[9] Bodini G, Zanella C, Crespi M, Lo Pumo S, Demarzo M, Savarino E et al. A randomized, 6-wk trial of a low FODMAP diet in patients with inflammatory bowel disease [Internet]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/…

[10] Limdi J. Dietary practices and inflammatory bowel disease [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/p…

[11] Ames B, Profet M, Gold L. Dietary pesticides (99.99% all natural). [Internet]. https://www.pnas.org/. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.pnas.org/content/p…

[12] Saravanan, Thirumalai, Asharani. International Journal of Research in Ayurveda and Pharmacy [Internet]. https://www.researchgate.net. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/p…

[13] Konijeti G, Kim N, Lewis J, Groven S, Chandrasekaran A, Grandhe S et al. Efficacy of the Autoimmune Protocol Diet for Inflammatory Bowel Disease [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/p…

[14] Cox S, Prince A, Myers C, Irving P, Lindsay J, Lomer M et al. Fermentable Carbohydrates [FODMAPs] Exacerbate Functional Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Randomised, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Cross-over, Re-challenge Trial [Internet]. https://academic.oup.com. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ecco-…

[15] Pedersen N, Ankersen D, Felding M, Wachmann H, Végh Z, Molzen L et al. Low-FODMAP diet reduces irritable bowel symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/p…

[16] 12. Albenberg L, Brensinger C, Wu Q, Gilroy E, Kappelman M, Sandler R et al. A Diet Low in Red and Processed Meat Does Not Reduce Rate of Crohn’s Disease Flares [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/p…

[17] Gajendran M, Loganathan P, Catinella A, Hashash J. A comprehensive review and update on Crohn’s disease [Internet]. https://www.sciencedirect.com. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/…