The Importance of Sleep for Your Immune System

The importance of a good night’s sleep can’t be overstated. Without the proper quantity and quality of sleep, our mood can deteriorate, our ability to focus often erodes, and we frequently feel run down, lethargic, and on edge. Research and anecdotal evidence all support the notion that sleep is integral to our overall health. In stressful times such as these, when a strong immune system is critical, quality sleep is paramount.

The latest sleep research suggests the quality and quantity of your sleep influences every component of human physiology. That influence extends to physical health, mortality, mental health, safety, learning, productivity, as well as our personal and professional relationships. Research even indicates that insufficient sleep shortens your life span. It’s no different when it comes to your immune system.

The COVID-19 pandemic affected each of us differently; still, improving one’s immune system is universally beneficial. Sources on social media and the Internet abound with recommendations to improve one’s immune system; in most cases nutritional solutions are suggested. While eating well and staying fit are important components to maintaining a healthy immune system, sleep is often neglected.

Despite consuming one-third of our lives, sleep is one of the last basic physiological needs to be understood; there is still a great deal to be learned. While we have analyzed much about the drive to eat, drink, and reproduce, for a long time physiologists knew little about the drive to sleep and why we “repeatedly and routinely lapse into a state of apparent coma.” Scientists were also puzzled why our “mind will often be filled with stunning, bizarre hallucinations”!(1)

From an evolutionary perspective, sleep would seem to be a foolish practice, since none of the other drives can be accomplished while we sleep. Importantly, it also leaves one vulnerable to predators. Consequently, we can reason that there must be significant benefits to sleep that outweigh the negatives. Indeed, it now appears that there is not one major organ or process within the brain that does not benefit from sleep.

For the past 30 years, a significant body of research has examined the effect of sleep on the immune system. The internal clock we all possess, also known as our circadian rhythm, exists in every one of our cells, including those of our immune system. A great deal of research explaining the impact of sleep on the immune system can be found for free at Pubmed.gov. (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12)

With an understanding that the strength of your immune system is highly dependent on the quality and quantity of our sleep, the question becomes: How does one improve both of these important factors? There is more to it than simply telling someone to get more sleep.

Sleep 101

First, let’s review some basic sleep physiology. Contrary to what many people believe, we do not all possess the same circadian rhythm, and we possess this internal clock independent of the sun’s cycle.

This was demonstrated in an experiment conducted by Professor Nathaniel Kleitman and his research assistant Bruce Richardson from the University of Chicago in 1938. (1) Loaded with enough food and water to last for 32 days, along with a host of measuring devices to assess their body temperatures and their waking and sleeping rhythms, the research team went deep into Mammoth Cave in Kentucky where there is no detectable sunlight. Removed from the daily cycle of light and dark, they discovered that their biological rhythms of sleep and wakefulness, together with body temperature, were not erratic but showed a predictable and repeating pattern of approximately fifteen hours of wakefulness along with bouts of about nine hours of sleep. Further, these repeating cycles were not exactly 24 hours in duration. Richardson, in his twenties, developed a sleep-wake cycle of between twenty-six and twenty-eight hours long, whereas Kleitman, in his forties, was closer to, but still longer than, 24 hours.

The discovery that our innate biological clock is not exactly 24 hours is what led to the nomenclature of circadian rhythm (circa – “around” dian – derivative of diam – “day”). That is, one that is approximately one day in length, but not precisely one day.

We now know that, on average, adult humans display an endogenous circadian clock of about 24 hours and 15 minutes in length, 900 seconds longer than the 24-hour rotation of the Earth. And while a number of repeating cues, such as food consumption, exercise and temperature fluctuations, can help to reset our internal clock to 24 hours exactly, daylight is the preferential signal to do this. Sitting in the middle of our brains is the suprachiasmatic nucleus, located where the optic nerves from our eyeballs cross. This very small mass of approximately 20,000 brain cells uses light from the sun to act as the central conductor of our biological processes.

When sleep is measured in a laboratory, electrodes are used to record signals coming from three different areas: brainwave activity, eye movement activity, and muscle activity. These signals are grouped together under the term polysomnography (PSG). Measuring these activities allows the creation of a sleep cycle, also known as a hypnogram. Figure 1 shows the structure of such a sleep cycle, and being familiar with this pattern is crucial to understanding the recommendations for improving the quantity and quality of sleep.

Figure 1. A Sleep Cycle Hypnogram recreated from Why We Sleep. (1)

In 1952, Eugene Aserinsky, a graduate student working in Professor Kleitman’s laboratory, made the important observation that the eyes would rapidly move from side-to-side during sleep, coinciding with very active brainwaves. (These characteristics were remarkably similar to those of a wide-awake brain.) There would also be periods when the eyes would be still. They named these different stages of sleep non-rapid eye movement (NREM) and rapid eye movement (REM). It was further discovered that these two phases of sleep would repeat in a somewhat consistent pattern.

Along with the help of William Dement, another graduate student, Aserinsky made the observation that REM sleep was associated with dreaming.

Since these early discoveries, NREM sleep has been further divided into four stages, with stages three and four representing the deepest stages of sleep. We cycle through all of these stages multiple times per night, and the time spent in each stage changes with each cycle. For example, the longest time spent in the REM stage occurs in the later cycles of sleep; the full cycle of all stages repeats consistently every 90 minutes.

Improving the Quality and Quantity of Sleep for Your Immune System Health

We learned earlier that the suprachiasmatic nucleus is the key to re-setting our internal clock. Consequently, it is important that we allow our sleep-wake cycle to get its daily correction by going outside in the morning (without sunglasses!)—preferably between the hours of 7 a.m. and 11 a.m. Try to make this a regular habit: Find an activity you can do outside for at least 45 minutes, if possible.

If you live at a latitude where the winter months are extremely short, and darkness pervades many months of the year, there are products that provide the light with the desired wavelength, such as alarm clocks that mimic the rising sun.

When improving sleep quality, it’s also helpful to understand the sleep cycle. Knowing that each cycle lasts 90 minutes, it stands to reason that sleeping for five cycles (7.5 hours) per night offers the ideal amount of sleep. This equates to 35 cycles per week. Now, to reduce your stress around sleep, consider this: Your goal should be to get 35 cycles per week instead of always getting five cycles per night. It helps that we are quite capable of catching up a few cycles here and there. (Let’s face it, life can easily get in the way of your planned bedtime.) It’s also helpful to realize that some individuals do fine even if they get fewer than 35 cycles, while others will find they do better if they get a few more.

It’s also important to know what the best bedtime is for your needs. To do this, first establish when your body wants to wake up in the morning. This is a personal choice, not a societal demand that forces you into its timetable. So, if you were living on a desert island with no commitments, when would your body want to wake up? This time is usually pretty consistent, even if you do not get to bed at a normal hour.

Our current situation of having to work from home might just be the perfect time for you to try and figure this out. Once you have established your wake-up time, you can establish your bedtime as 7.5 hours prior. So, as an example, if you determine that your body likes to wake up at 6 a.m., then you should try to fall asleep at 10:30 p.m. the previous night. In order to fall asleep, you should get into a bedtime routine that helps you do so—whether it’s taking a hot bath or reading a book, find something that helps. If you must use your computer late at night, purchase a pair of glasses that block blue light waves, which have been shown to disrupt sleep quality.

Morning Larks and Night Owls

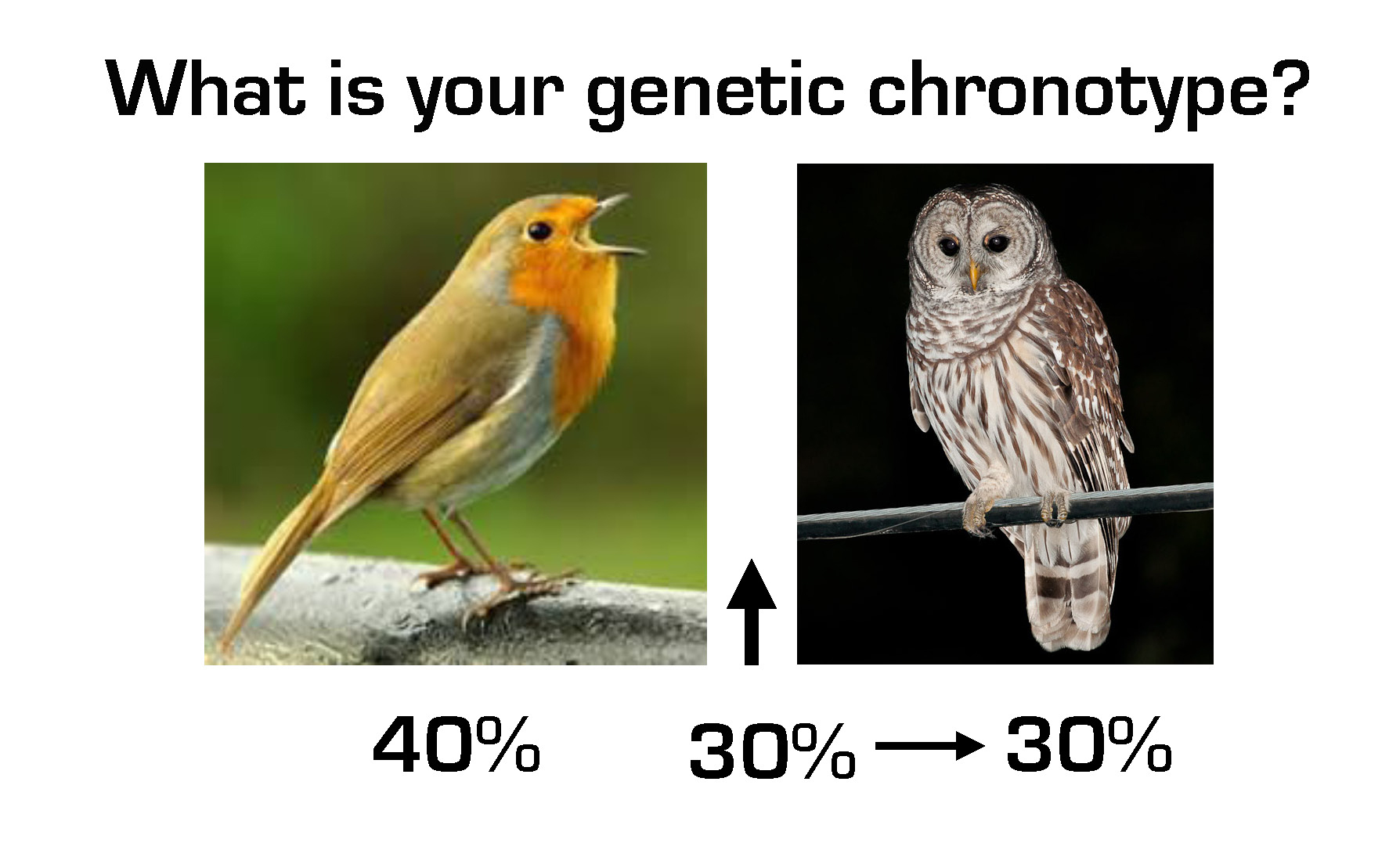

Some of you may feel that 6 a.m. is ridiculously early and might even struggle to get out of bed before 9 a.m. Herein lies the issue of your genetic chronotype. If 9 a.m. sounds more appealing, you are not a morning lark (as sleep researchers like to call it). Rather, you are a night owl (i.e., one that functions very well long into the night). For too long, night owls have been labeled lazy for struggling to rise early, and society has created a timetable that favors the morning lark. About 40 percent of us are morning larks, 30 percent are night owls, and a further 30 percent are a mix of the two (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Genetic Chronotype Percentages

From an evolutionary perspective, this makes perfect sense, as in primitive times staggering our sleep within a tribe would provide greater security from predators.

But, because society has created a timetable that favors the morning lark, night owls typically get less sleep. As a result, they have higher rates of depression, anxiety, diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease.

Consequently, if you are a night owl and care about your health, you need to find a job with an employer that understands this issue and provides flexible hours. The employer would benefit from increased productivity and you would help your health and longevity. Thankfully, this is now happening. So, for the individual that likes to wake at 9 a.m., your bedtime is 1:30 a.m. Own and embrace it!

Catch the Next Cycle

Regardless of your chronotype, and despite the best plans, there are going to be many occasions when you miss your bedtime. If your bedtime is 10:30 p.m. and you miss it, do not rush to get to bed by 11 p.m. (i.e., 30 minutes into your intended first cycle). Instead, you will be better off going to bed at the start time of your intended second cycle (i.e., 90 minutes past your bedtime) at midnight. You will then get four good cycles. Later , if you are able and feel you need it, you can get another full 90-minute cycle as a nap the following day. If 90 minutes is not possible, a 20-30 minute nap can help; avoid a 45-60 minute nap since you will be waking out of the deeper stages of sleep.

And if you have a hard time getting to sleep at the start of one of your cycles (and not just the first cycle, since many people wake following a REM stage when they are close to wakefulness), do not lie there struggling. If you have not fallen asleep after about 15 minutes of trying, get up and keep yourself busy until the start of another cycle just as in the above example when missing your bedtime.

These approaches will often relieve the pressure and anxiety many feel when sleep becomes a challenge.

For More Help with Your Sleep

Obviously, there is a lot more to developing good sleep protocols. However, the above tips are where we’d recommend you start if you are trying to improve the quality and quantity of your sleep for your immune system.

If you want to go deeper or need greater help, consider the writing of Nick Littlehales, a world-renowned and self-proclaimed “sleep coach” who has worked with the likes of Manchester United FC, Manchester City FC, Liverpool FC, Real Madrid C.F., UK Athletics & British Cycling, and many top corporations to improve the sleep of their athletes and employees. His book Sleep (13) is a great resource. He also has a lot of tips you can follow on his Instagram feed @_sportsleepcoach. You may also consider Why We Sleep by Mathew Walker, PhD. (1)

References

1. Walker M, Why We Sleep, Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams. Scribner, 2017.

2. Mazzoccoli G, Vinciguerra M, Carbone A, Relógio A. The Circadian Clock, the Immune System, and Viral Infections: The Intricate Relationship Between Biological Time and Host-Virus Interaction. Pathogens. 2020 Jan 27;9(2). pii: E83. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9020083. Review. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0817/9/2/83/htm

3. Haspel JA, Anafi R, Brown MK, Cermakian N, Depner C, Desplats P, Gelman AE, Haack M, Jelic S, Kim BS, Laposky AD, Lee YC, Mongodin E, Prather AA, Prendergast BJ, Reardon C, Shaw AC, Sengupta S, Szentirmai É, Thakkar M, Walker WE, Solt LA. Perfect timing: circadian rhythms, sleep, and immunity – an NIH workshop summary. JCI Insight. 2020 Jan 16;5(1). pii: 131487. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.131487. Review. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7030790/

4. Oikonomou G, Prober DA. Linking immunity and sickness-induced sleep. Science. 2019 Feb 1;363(6426):455-456. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw2113. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6628894/

5. Barik S. Molecular Interactions between Pathogens and the Circadian Clock. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Nov 20;20(23). pii: E5824. doi: 10.3390/ijms20235824. Review. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6928883/

6. Ibarra-Coronado EG, Pérez-Torres A, Pantaleón-Martínez AM, Velazquéz-Moctezuma J, Rodriguez-Mata V, Morales-Montor J. Innate immunity modulation in the duodenal mucosa induced by REM sleep deprivation during infection with Trichinella spirallis. Sci Rep. 2017 Apr 4;7:45528. doi: 10.1038/srep45528. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5379483/

7. Irwin MR, Opp MR. Sleep Health: Reciprocal Regulation of Sleep and Innate Immunity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017 Jan;42(1):129-155. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.148. Epub 2016 Aug 11. Review. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5143488/

8. Almeida CM, Malheiro A. Sleep, immunity and shift workers: A review. Sleep Sci. 2016 Jul-Sep;9(3):164-168. doi: 10.1016/j.slsci.2016.10.007. Epub 2016 Nov 6. Review. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5241621/

9. Opp MR, Krueger JM. Sleep and immunity: A growing field with clinical impact. Brain Behav Immun. 2015 Jul;47:1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.03.011. Epub 2015 Apr 4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4685944/

10. Ibarra-Coronado EG, Pantaleón-Martínez AM, Velazquéz-Moctezuma J, Prospéro-García O, Méndez-Díaz M, Pérez-Tapia M, Pavón L, Morales-Montor J. The Bidirectional Relationship between Sleep and Immunity against Infections. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:678164. doi: 10.1155/2015/678164. Epub 2015 Aug 31. Review. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4568388/

11. Ali T, Choe J, Awab A, Wagener TL, Orr WC. Sleep, immunity and inflammation in gastrointestinal disorders. World J Gastroenterol. 2013 Dec 28;19(48):9231-9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i48.9231. Review. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3882397/

12. Zielinski MR, Krueger JM. Sleep and innate immunity. Front Biosci (Schol Ed). 2011 Jan 1;3:632-42. Review. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3645929/

13. Littlehales N, Sleep, The Myth of 8 Hours, the Power of Naps . . . and the New Plan to Recharge Your Body and Mind. Da Capo Press, 2016.

Mark J. Smith, Ph.D.

One of the original members of the Paleo movement, Mark J. Smith, Ph.D., has spent nearly 30 years advocating for the benefits of Paleo nutrition.

More About The Author