Is Sugar Addictive?

Sugar is likely the most overconsumed substance in the modern world.1 On top of soda (sugar water essentially), sugar is surreptitiously added to many processed foods in America.2 As a result, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) now reports that the average American ingests 150-170 pounds of sugar per year.3 And this overconsumption of sugar may very well be killing us.

Sugar is the precursor (the “canary in the coalmine”) to numerous diseases and unhealthy conditions. Diabetes? Check.4 Obesity? Check.5 Even Alzheimer’s has been directly linked to too much sugar consumption.6 In fact, there is hardly a single condition or disease that can’t be correlated with overconsumption of sugar in some fashion.7

Still, scientists debate how addictive sugar really is, and whether or not it is truly a substance we should call “dangerous”.8 There have been many research attempts to show just how potentially addictive sugar can be, and even a variety of (somewhat novel) ideas on just how to establish if it is addictive.9, 10, 11, 12

The truth is that sugar is in big business with players on both sides of this debate—from industry bigwigs promoting its consumption to cities taxing sugar-sweetened beverages. Somewhere along the lines the science gets lost. So let’s take a deeper look at what the research really says about sugar and addiction.

The Evidence for Sugar Addiction

Perhaps the most interesting evidence for sugar addiction lies in the brain’s varying responses to its ingestion.13 The hypothalamus, which plays a key role in the homeostatic regulation of food intake, is activated by glucose or fructose in adolescents who are obese. But it is not activated in those who are lean.14

Which raises the question: Is obesity a cause or effect of this neuronal response? Is the brain hardwired to crave sugar, or do our brains rewire themselves because of our eating habits? This is one of the main reasons why scientists have yet to firmly establish whether sugar is truly an addictive substance.15

When we talk about sugar, we are mostly talking about fructose and glucose. Although both provide the body with energy, fructose has a more intense sweetness, and stimulates the striatal complex (the area of the brain closely linked with rewarding behaviors, like drug ingestion or gambling).16

Unlike glucose, fructose likely overrides our homeostatic control of eating,17 meaning that fructose may cause us to overeat, while glucose may not.18 In 2015, researchers showed that ingestion of fructose results in greater activation of brain regions involved in attention and reward processing.19 And in 2016, a study in Diabetes concluded that there is greater perfusion in the ventral striatum when fructose is consumed.20 Fructose altered this key component of the brain’s reward system differently than glucose consumption.

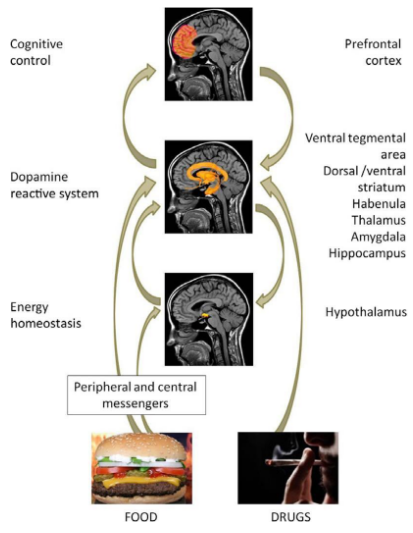

There has been a lot of research in the area of sugar addiction.21, 22 Much of the best research was led by Nora Volkow, who established that there were overlapping neuronal circuits in addiction and obesity.23 This means that our brains can react very similarly to sugar addiction as they do to alcohol, cocaine, or other hard drugs. Volkow’s research is very clear and overwhelming: Sugar acts nearly identically to other substances of abuse.24

Perhaps one of the clearest ways to see the addictive nature of sugary foods is to look at their opposite—vegetables—and the effects that these nutrient-rich substances have on our brains and bodies. These foods provide essential nutrients, elicit no cravings or negative effects, and in fact stop hunger and cravings.26

The Industry Sweetens Us on Sugar

While there’s clear evidence of addiction, unfortunately, politics and big business come into play. This may sound a touch like hyperbole, but if we all were to adopt a Paleo Diet—with no added sugars—the big food companies would likely go out of business. That’s because they heavily rely on sugar to prop up otherwise flavorless foods.27 They take advantage of the fact that our brains can never get enough sugar.28 While we can clearly see this with soda, the practice has been extended to nearly all processed foods—even children’s breakfast cereals.29

The food industry bigwigs understand that sugar is addictive, as shown in Michael Moss’s award-winning book, Salt Sugar Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us. Former executives of tobacco companies now run big food companies,30 and these executives are involved in important decisions like whether or not to finally establish a percent daily value for total sugar ingestion31 (a percent daily value exists for added sugars—a change which only came about in 2020—but there is still no daily value for total sugars).

Fortunately for us, the World Health Organization (WHO) has established a guideline for sugar consumption at a very reasonable 25 grams per day. However, largely due to politics, they had to publicly state that even 50 grams/day would be an improvement over our current situation! Their official note was that lowering your intake to 25 grams per day would have “additional health benefits.”32

A Less Sugary Diet

A Paleo Diet is rich in essential nutrients, high in muscle-building protein, and loaded with brain-friendly fats. It is also devoid of craving-inducing, processed sugars and has shown to be beneficial for those with diabetes.33 Ultimately, the scientific evidence and results speak for themselves.

But this doesn’t mean you have to cut sugar out of your life completely. Moderation of sugary, processed foods in accordance with the 85/15 principle is still enough to curb cravings and reduce markers of chronic disease. A sweet treat every once in a while won’t kill you. Just make sure it’s not turning into a habit that’s tough to break.

References

[1] Yang Q, Zhang Z, Gregg EW, Flanders WD, Merritt R, Hu FB. Added sugar intake and cardiovascular diseases mortality among US adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):516-24.

[2] Martínez Steele E, Baraldi LG, Louzada ML, Moubarac JC, Mozaffarian D, Monteiro CA. Ultra-processed foods and added sugars in the US diet: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3):e009892.

[3] Available at: //www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/sugar-and-sweeteners-yearbook-tables.aspx. Accessed August 14, 2016.

[4] Basu S, Yoffe P, Hills N, Lustig RH. The relationship of sugar to population-level diabetes prevalence: an econometric analysis of repeated cross-sectional data. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e57873.

[5] Musselman LP, Fink JL, Narzinski K, et al. A high-sugar diet produces obesity and insulin resistance in wild-type Drosophila. Dis Model Mech. 2011;4(6):842-9.

[6] Crane PK, Walker R, Hubbard RA, et al. Glucose levels and risk of dementia. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(6):540-8.

[7] Stanhope KL. Sugar consumption, metabolic disease and obesity: The state of the controversy. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2016;53(1):52-67.

[8] Westwater ML, Fletcher PC, Ziauddeen H. Sugar addiction: the state of the science. Eur J Nutr. 2016;

[9] Lenoir M, Serre F, Cantin L, Ahmed SH. Intense sweetness surpasses cocaine reward. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(8):e698.

[10] Ahmed SH, Guillem K, Vandaele Y. Sugar addiction: pushing the drug-sugar analogy to the limit. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013;16(4):434-9.

[11] Avena NM, Rada P, Hoebel BG. Evidence for sugar addiction: behavioral and neurochemical effects of intermittent, excessive sugar intake. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32(1):20-39.

[12] Fortuna JL. Sweet preference, sugar addiction and the familial history of alcohol dependence: shared neural pathways and genes. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2010;42(2):147-51.

[13] Tryon MS, Stanhope KL, Epel ES, et al. Excessive Sugar Consumption May Be a Difficult Habit to Break: A View From the Brain and Body. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(6):2239-47.

[14] Jastreboff AM, Sinha R, Arora J, et al. Altered brain response to drinking glucose and fructose in obese adolescents. Diabetes 2016;65:1929–1939

[15] Bray GA. Is Sugar Addictive?. Diabetes. 2016;65(7):1797-9.

[16] Page KA, Chan O, Arora J, et al. Effects of fructose vs glucose on regional cerebral blood flow in brain regions involved with appetite and reward pathways. JAMA. 2013;309(1):63-70.

[17] Bray GA. Obesity: A failure of homeostasis due to hedonic rewards: Response to the letter from Gary Taubes. Obes Rev 2008;10:99–102

[18] Lustig RH. Fructose: metabolic, hedonic, and societal parallels with ethanol. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(9):1307-21.

[19] Luo S, Monterosso JR, Sarpelleh K, Page KA. Differential effects of fructose versus glucose on brain and appetitive responses to food cues and decisions for food rewards. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(20):6509-14.

[20] Jastreboff AM, Sinha R, Arora J, et al. Altered Brain Response to Drinking Glucose and Fructose in Obese Adolescents. Diabetes. 2016;65(7):1929-39.

[21] Rada P, Avena NM, Hoebel BG. Daily bingeing on sugar repeatedly releases dopamine in the accumbens shell. Neuroscience. 2005;134(3):737-44.

[22] Yanovski S. Sugar and fat: cravings and aversions. J Nutr. 2003;133(3):835S-837S.

[23] Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Tomasi D, Baler R. Food and drug reward: overlapping circuits in human obesity and addiction. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2012;11:1-24.

[24] Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Tomasi D, Baler RD. Obesity and addiction: neurobiological overlaps. Obes Rev. 2013;14(1):2-18.

[25] Volkow, N. D., Wang, G.-J., Tomasi, D., & Baler, R. D. (2013). Pro v Con Reviews: Is Food Addictive?: Obesity and addiction: neurobiological overlaps.Obesity Reviews : An Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 14(1), 2–18. //doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01031.x

[26] Gómez-pinilla F. Brain foods: the effects of nutrients on brain function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(7):568-78.

[27] Available at: //www.nytimes.com/2013/02/24/magazine/the-extraordinary-science-of-junk-food.html. Accessed August 14, 2016.

[28] Tryon MS, Stanhope KL, Epel ES, et al. Excessive Sugar Consumption May Be a Difficult Habit to Break: A View From the Brain and Body. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(6):2239-47.

[29] Harris JL, Graff SK. Protecting young people from junk food advertising: implications of psychological research for First Amendment law. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(2):214-22.

[30] Moss, Michael. Salt, Sugar, Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us. New York: Random House, 2013.

[31] Available at: //well.blogs.nytimes.com/2016/06/08/is-sugar-really-bad-for-you-it-depends/. Accessed August 14, 2016.

[32] Available at: //www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2015/sugar-guideline/en/. “WHO Guideline: Sugar Consumption Recommendation.” World Health Organization. Accessed August 14, 2016.

[33] Jönsson T, Granfeldt Y, Lindeberg S, Hallberg AC. Subjective satiety and other experiences of a Paleolithic diet compared to a diabetes diet in patients with type 2 diabetes. Nutr J. 2013;12:105.

Casey Thaler, B.A., NASM-CPT, FNS

Casey Thaler is a certified personal trainer and nutrition specialist.

More About The Author