How Evolution Shaped the Human Diet

While evolution has moved us in a particular direction over millennia, that doesn’t mean it’s made us all the same.

For example, evolution has set the average human height around 5 feet, 8 inches. But that doesn’t mean that we are all 5’8”. That’s just the typical height. Most of us are somewhere between 5’4” and 6’1”, and a small percentage are outliers.

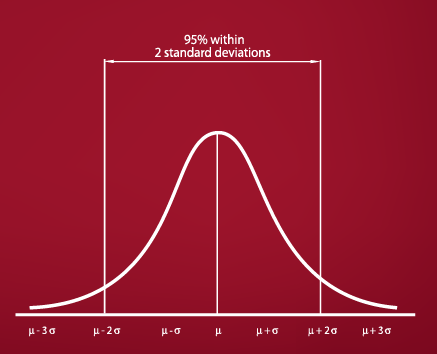

This concept of distribution is called a bell-shaped curve, and it is the foundation of evolution. Height is just one attribute. We have thousands—if not millions—of genetically determined attributes, and each one is on a bell-shaped curve with the most common trait at the peak. Most of us fit within a narrow range from that peak. In scientific terms, 95% of us are within two standard deviations:

And just like with height there are some people who are outside of those two standard deviations, but they are outliers. Each of us will be within those two standard deviations for the vast majority of our traits. That said, almost all of us will be an outlier in at least one attribute.

The Bell-Shaped Curve and Diet

The laws of the bell-shaped curve apply to diet as well. We can define an optimal diet at the peak of the curve, but the truth is there’s going to be a fair amount of individual variance.

Avocados may be a superfood at the peak of the curve for most of us, but there’s still some who should avoid it. Other foods at the peak of the curve are those that were available to us throughout our evolution, like fresh fruits, vegetables, natural meats, fish, eggs, nuts, and seeds.

Certainly we’ve all heard of someone who ate only hamburgers and candy bars, smoked a pack of cigarettes per day, and lived into their nineties. He or she is the outlier. They are the 5%. And just as you wouldn’t want to pick the height of a door frame based on the very small number of four-foot-tall people, you don’t want to base your dietary choices on what you see one outlier eating, either. This is why “my friend ate fill-in-the-blank every day and lived to 90” is a bad scientific argument.

What Happens When There’s an Evolutionary Change

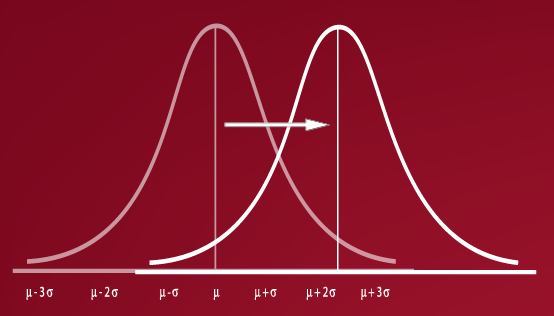

Even though Darwin never actually said this, we’ve all heard the term “survival of the fittest.” Despite what some extreme sport athletes want you to believe, it does not mean the fittest eliminated the weak. In fact, we actually evolved to be communal: We survive by supporting one another. Survival of the fittest really means survival of those in the middle of the curve.

When there have been evolutionary changes in the past, environmental pressure caused the middle of the curve to shift. The environment change gave outliers on one side of the curve a genetic advantage that causes them to flourish, while what had once been the optimal characteristic became an outlier:

For example, imagine a group of humans gets stuck on an island with limited food. The smaller humans in the group—who need fewer calories—would have a genetic advantage, while larger humans would not survive. Over a few generations, the curve representing human stature would shift to a smaller stature. This is what happened with the Pygmies.

This is also why eating the foods that were available to us through our millions of years of evolution became the optimal human diet. Our ancestors who were most suited to those foods thrived, while those who were not suited to those foods unfortunately became the outliers and disappeared over time. The curve shifted until the foods that were available were the peak of the curve.

So, yes, that theoretically means that if all we ate was pizza, over many generations, pizza would become our optimal food. But evolution is slow moving, measured in millennia. For the “pizza curve” to shift, those of us at the center of the original curve must die off so the outliers can take over. In other words, don’t hold your breath waiting for that shift to happen!

The Modern Western Diet Is Still an Outlier

Of course, the problem has to do with more than just pizza. Around 70% of the foods that comprise the modern diet (grain products, vegetable oils, dairy, refined sugar, and alcohol) were introduced in the past 10,000 years and are completely out of line with the center of the curve.[1] While that might sound like a long time, 10,000 years is not nearly enough for evolution to shift the curve. In fact, many of the foods we now eat only appeared in any significant quantity within the last 200 years. Refined flour, for example, appeared after the invention of steel roller mills in the late 1800s.

As a result, many people now eat a diet that is, in effect, an outlier on the dietary bell-shaped curve. Because of that, we have chronic illnesses, collectively referred to as the “Diseases of Civilization.”

Some have argued against this evolutionary view of diet, pointing out that epigenetic changes allow adaptations within a single generation. However, while epigenetics may move individuals a little to the left or right on the curve, they don’t move the entire curve. And it can even be argued that epigenetic changes can work against us. Unprocessed grains are normally poisonous to humans. It’s possible that epigenetic changes have allowed us to better tolerate them in the short run, exposing us to bigger, long-term consequences.

The Paleo Diet® Is at the Center of the Dietary Curve

The Paleo Diet is based on this evolutionary approach to diet. As Theodosius Dobzhansky, a well-known Ukrainian evolutionary biologist said, “Nothing in biology makes sense, except under the light of evolution.”

At the center of the bell-shaped curve are the foods we evolved to eat. That doesn’t mean there is just one correct way to eat—our Paleolithic ancestors ate different foods depending on where they lived. The optimal human diet is a range, not a point, and most of us sit somewhere in that range—or two standard deviations of the peak of the curve.

So, we are not saying there is one diet that is perfect for everyone. What we are saying is that you shouldn’t start with a Western diet, which we know is an outlier. Our recommendation instead is to start with the foods at the center of the curve and then find which side of the curve you’re more suited to—more or less fruit, more plant-based, or more animal-based. The one thing we can tell you for certain: grains, refined sugar, vegetable oils, dairy, and alcohol, in any regular quantity, are the outliers.

References

- Eaton, S.B., M. Konner, and M. Shostak, Stone agers in the fast lane: chronic degenerative diseases in evolutionary perspective. Am J Med, 1988. 84(4): p. 739-49.

Trevor Connor, M.S.

Dr. Loren Cordain’s final graduate student, Trevor Connor, M.S., brings more than a decade of nutrition and physiology expertise to spearhead the new Paleo Diet team.

More About The Author