Wheat Series Part 4: Wheat as a Harmful Dietary Antigen

While a home invasion is something most of us will hopefully never experience, dealing with invaders is something our bodies have to handle thousands of times each day. And just like a thief entering your house, it would seem the job of identifying the invader—bacteria and viruses—should be a simple task. But it’s not.

The immune system has to deal with dark and confusing scenarios as it tries to differentiate dangerous invaders from our own cells, beneficial microflora, and food.1-3 Fortunately, it has evolved remarkably complex systems that make it very good at determining which is which.

One food, however, is even better at breaking in and misdirecting our internal security systems: Wheat.

In the first three installments of this series on wheat, we talked about how wheat affects the three things that can cause the digestive immune system to dysfunction. The first was increased permeability (Part 2), the second was excess bacterial stress (Part 3). The third is the subject of this post: Harmful dietary antigens.

Antigens: Identifying the Invader

Antigens are critically important to our immune defenses. In fact, without them, most of our immune system wouldn’t be able to function. Which begs the question—what exactly are antigens?

They are just molecules. And not really any special type of molecule. Antigens exist in everything: bacteria, viruses, our food, even our own cells. As long as our immune cells can bind to it and identify it, it’s an antigen.4

Certain cells in our immune system, called antigen presenting cells (APCs), travel around our bodies “sampling” everything they encounter. They aren’t particular—they’re just as likely to check out our own cells as a foreign bacterium. They chew everything they sample into small molecules and present these antigens to the brains of our immune system: T cells.4

T cells are trained from birth not to respond to our own unique self-antigens, which makes them remarkably good at identifying anything foreign. Together, T cells and APCs determine when an antigen isn’t itself and, more importantly, if it’s something to be worried about.5

Think of an antigen as an ID card. APCs and T cells are the police hunting through the house for anyone who doesn’t belong. The APC is the one who takes the intruder’s ID, and the T cell looks over their identification and decides if they belong or not.

The problem is that ID cards are easy to fake. Some viruses have evolved the ability to mimic our own antigens in an attempt evade detection.6, 7 And not everything from the outside is bad. Beneficial bacteria in our gut are foreign, but we’ve learned to live in synergy with them.2, 3, 8 Likewise, all food is technically foreign, but an immune response to everything we eat would lead to debilitating allergic reactions and worse.9-11

To deal with this extra level of complexity, our immune systems have developed two sophisticated “interrogation” techniques: co-stimulation and oral tolerance.

Co-stimulation (or the Second Signal)

Identifying an antigen as foreign isn’t enough for a T cell to start an immune response. The T cell must also receive an activating signal from the APC as it presents the antigen. The APC gives this second signal when it has been exposed to a large amount of the antigen or if the body is in an inflamed state.5, 12-15

Co-stimulation is the equivalent of the T cell asking the APC, “I don’t recognize this guy, should I call in backup?” Surprisingly, the tough-guy APC generally replies, “What, this wimp? Nah, I can take him.”

Oral Tolerance

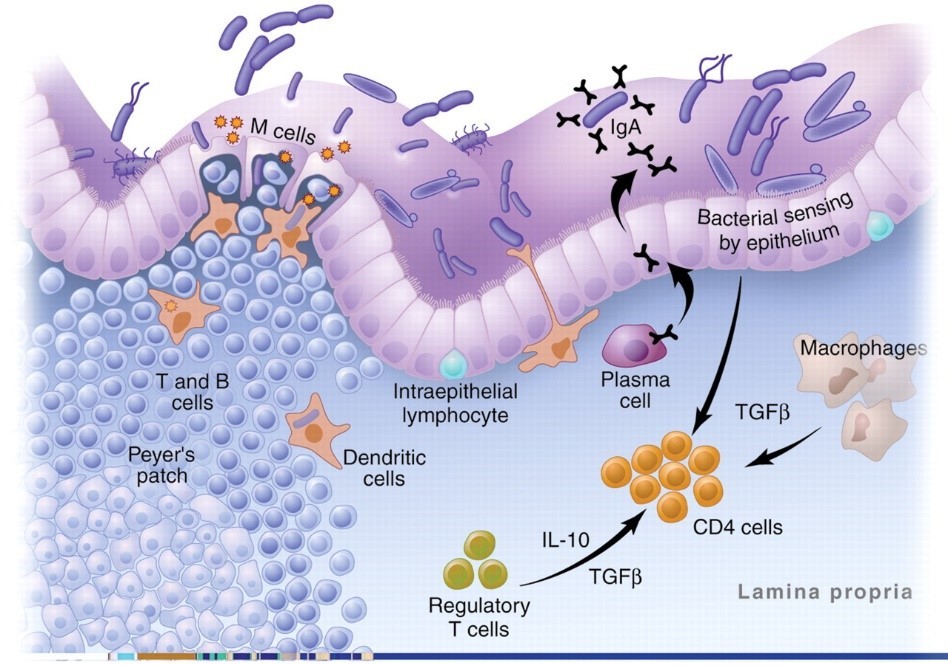

Oral tolerance is a fancy term for not reacting to food. A type of APC, called dendritic cells (DCs), specializes in reaching into the gut to sample food particles and microflora. Most of the time it presents the antigens with the message: “This is food. Don’t do anything.”1, 12, 14 DCs work in conjunction with a special T cell called T Regulatory (Treg) cells that respond to self-antigens instead of foreigners. But unlike other T cells, when activated, Treg cells suppress the immune system.12, 16-18 Fortunately, in our bodies, these two cells are in control most of the time.

The image below shows the antigen identification system in action. Plasma cells, macrophages, and DCs are all APCs. As you can see, in the healthy gut, Treg cells dominate:19

Wheat: The Master Criminal

Now we’ll talk about how wheat is essentially a “master criminal” able to flip our antigen identification system on its head. But unlike a virus, wheat doesn’t break the system to try to evade detection. Instead, it intentionally sets off the alarms and provokes the immune system to respond. Tragically, it’s also very good at getting immune cells to attack the wrong target.20

The Lock Picker

Part 2 of this series explains how wheat effectively opens the tight junctions of our gut allowing bacteria, large molecules, and gliadin from wheat itself to enter the body.21-24 But that’s not the only way wheat breaks in.

A protein in wheat called wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) is very good at binding to the cells in our digestive tract and passing right through them into our bloodstream.13, 25, 26 WGA can also bind to other particles. So not only can it gain entry into circulation, but it can carry antigens from the gut with it.27, 28

The Police Provoker

We know the immune system doesn’t automatically respond to foreign antigens. It first needs a co-stimulation before calling in the big guns. The first thing the immune system needs is exposure to a large quantity of antigens. Wheat essentially flings open the doors of our intestinal barrier, allowing a huge flow of antigens from the gut into the body.

The second thing that gets APCs to provide the co-stimulation is inflammation. In Part 3 of this series, I explained how wheat tricks the body into believing it is under perpetual bacterial stress.29-33 This creates a constant inflammatory state that causes the once-suppressive DCs to flip and start activating the immune system.34, 35 Other APCs follow suit.30, 32, 36-39

In short, wheat ensures there’s a co-stimulation. Wheat also breaks oral tolerance.

WGA is able to enter the body bypassing all the mechanisms of oral tolerance.25, 28 So, the first time WGA and the harmful dietary antigens bound to it are exposed to the immune system is in circulation, where the response is almost always inflammatory.

Worse, in multiple studies of wheat’s effect on mice and humans, wheat reduced levels of Treg (the immune suppressors) in favor of a type of T cell called Th17.29, 34, 40 We’ll explore this shift in greater detail in Part 5; all you need to know for now is Th17 is a loose cannon who shoots first, asks questions later.41-43

The Red Herring

The above process is the definition of an autoimmune disease. It is a condition where the immune system identifies self-antigens as foreign and attacks its own body.44 One popular theory of how autoimmune disease comes about is the viral mimicry theory. A virus enters the body that mimics self-antigens.14 In the process of fighting the virus, the immune system ends up identifying the mimicked self-antigens as foreign.6, 7, 45

For this to happen, the body has to be in an inflamed state. That way APCs provide the co-stimulation required, and they also suppress Treg cells which would otherwise prevent a reaction to self. This is why the theorists looked at viruses. Not only would they mimic self-antigens, but they’d also create the necessary inflammation.7, 45

However, we’ve just seen that wheat does an equally good job of providing the co-stimulation and shutting down Treg cells. And wheat may provide the mimicry as well, so forget the virus.20, 44, 46-48

Of the over 100 autoimmune conditions identified, the trigger has been discovered for only a handful. One of those is celiac disease. In this condition, gliadin from wheat binds a protein in the body called tissue transglutaminase (tTG). The immune system reacts to tTG-gliadin antigens causing it to attack the digestive tract.39, 49, 50

Gliadin may also cross-react with neural components of the brain and contribute to conditions like multiple sclerosis, gluten ataxia, and autism.46, 47, 51 Similarly, WGA is able to bind to many different cells once inside the body.20, 26, 31 While responding to WGA, the immune system will sometimes also react to its binding tissues.20, 52

Fortunately, while wheat can dysregulate the immune system in all of us, not everyone who eats it develops an autoimmune disease. In the final part of this series we’ll talk about how genetic susceptibility is required for disease.

Explore the rest of our Wheat Series:

Part 1: The Digestive Immune System

Part 2: Wheat and Gluten’s Effect on Intestinal Permeability

Part 3: How Wheat Mimics Bacteria

NEXT: How Wheat Can Trigger Chronic Disease

References

[1]du Pre, M.F. and J.N. Samsom, Adaptive T-cell responses regulating oral tolerance to protein antigen. Allergy, 2011. 66(4): p. 478-90.

[2]McFall-Ngai, M., Adaptive immunity: care for the community. Nature, 2007. 445(7124): p. 153.

[3]Ohnmacht, C., et al., Intestinal microbiota, evolution of the immune system and the bad reputation of pro-inflammatory immunity. Cell Microbiol, 2011. 13(5): p. 653-9.

[4]Murphy, K., et al., Janeway’s immunobiology. 8th ed. 2012, New York: Garland Science. xix, 868 p.

[5]Lenschow, D.J., T.L. Walunas, and J.A. Bluestone, CD28/B7 system of T cell costimulation. Annu Rev Immunol, 1996. 14: p. 233-58.

[6]Oldstone, M.B.A., Molecular mimicry and immune-mediated diseases. Faseb Journal, 1998. 12(13): p. 1255-1265.

[7]Wucherpfennig, K.W. and J.L. Strominger, MOLECULAR MIMICRY IN T-CELL-MEDIATED AUTOIMMUNITY – VIRAL PEPTIDES ACTIVATE HUMAN T-CELL CLONES SPECIFIC FOR MYELIN BASIC-PROTEIN. Cell, 1995. 80(5): p. 695-705.

[8]Smith, P.D., et al.,Intestinal macrophages and response to microbial encroachment. Mucosal Immunol, 2011. 4 (1): p. 31-42.

[9]Ahmed, T., et al., Immune response to food antigens: kinetics of food-specific antibodies in the normal population. Acta Paediatr Jpn, 1997. 39(3): p. 322-8.

[10]Seibold, F., Food-induced immune responses as origin of bowel disease? Digestion, 2005. 71(4): p. 251-260.

[11]Ganeshan, K., et al., Impairing oral tolerance promotes allergy and anaphylaxis: A new murine food allergy model. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 2009. 123(1): p. 231-238.

[12]Williamson, E., G.M. Westrich, and J.L. Viney, Modulating dendritic cells to optimize mucosal immunization protocols. J Immunol, 1999. 163(7): p. 3668-75.

[13]de Aizpurua, H.J. and G.J. Russell-Jones, Oral vaccination. Identification of classes of proteins that provoke an immune response upon oral feeding. J Exp Med, 1988. 167(2): p. 440-51.

[14]Stepniak, D. and F. Koning, Celiac disease–sandwiched between innate and adaptive immunity. Hum Immunol, 2006. 67(6): p. 460-8.

[15]Scalapino, K.J. and D.I. Daikh, CTLA-4: a key regulatory point in the control of autoimmune disease. Immunol Rev, 2008. 223: p. 143-55.

[16]Battaglia, M., et al., IL-10-producing T regulatory type 1 cells and oral tolerance. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2004. 1029: p. 142-53.

[17]Wing, K. and S. Sakaguchi, Regulatory T cells exert checks and balances on self tolerance and autoimmunity. Nat Immunol, 2010. 11(1): p. 7-13.

[18]Veldman, C., A. Nagel, and M. Hertl, Type I regulatory T cells in autoimmunity and inflammatory diseases. International Archives of Allergy and Immunology, 2006. 140(2): p. 174-183.

[19]Macdonald, T.T. and G. Monteleone, Immunity, inflammation, and allergy in the gut. Science, 2005. 307(5717): p. 1920-5.

[20]Vojdani, A., Lectins, agglutinins, and their roles in autoimmune reactivities. Altern Ther Health Med, 2015. 21 Suppl 1: p. 46-51.

[21]Drago, S., et al., Gliadin, zonulin and gut permeability: Effects on celiac and non-celiac intestinal mucosa and intestinal cell lines. Scand J Gastroenterol, 2006. 41(4): p. 408-19.

[22]Fasano, A., Physiological, Pathological, and Therapeutic Implications of Zonulin-Mediated Intestinal Barrier Modulation Living Life on the Edge of the Wall. American Journal of Pathology, 2008. 173(5): p. 1243-1252.

[23]Fasano, A., Surprises from celiac disease. Sci Am, 2009. 301(2): p. 54-61.

[24]Lammers, K.M., et al., Gliadin induces an increase in intestinal permeability and zonulin release by binding to the chemokine receptor CXCR3. Gastroenterology, 2008. 135(1): p. 194-204 e3.

[25]Lavelle, E.C., et al., Mucosal immunogenicity of plant lectins in mice. Immunology, 2000. 99(1): p. 30-7.

[26]Pusztai, A., et al., Antinutritive effects of wheat-germ agglutinin and other N-acetylglucosamine-specific lectins. Br J Nutr, 1993. 70(1): p. 313-21.

[27]Ertl, B., et al., Lectin-mediated bioadhesion: preparation, stability and caco-2 binding of wheat germ agglutinin-functionalized Poly(D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid)-microspheres. J Drug Target, 2000. 8(3): p. 173-84.

[28]Gabor, F., M. Stangl, and M. Wirth, Lectin-mediated bioadhesion: binding characteristics of plant lectins on the enterocyte-like cell lines Caco-2, HT-29 and HCT-8. J Control Release, 1998. 55(2-3): p. 131-42.

[29]Antvorskov, J.C., et al., Dietary gluten alters the balance of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in T cells of BALB/c mice. Immunology, 2013. 138(1): p. 23-33.

[30]Bernardo, D., et al., Is gliadin really safe for non-coeliac individuals? Production of interleukin 15 in biopsy culture from non-coeliac individuals challenged with gliadin peptides. Gut, 2007. 56(6): p. 889-890.

[31]Dalla Pellegrina, C., et al., Effects of wheat germ agglutinin on human gastrointestinal epithelium: insights from an experimental model of immune/epithelial cell interaction. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2009. 237(2): p. 146-53.

[32]Jelinkova, L., et al., Gliadin stimulates human monocytes to production of IL-8 and TNF-alpha through a mechanism involving NF-kappaB. FEBS Lett, 2004. 571(1-3): p. 81-5.

[33]Junker, Y., et al., Wheat amylase trypsin inhibitors drive intestinal inflammation via activation of toll-like receptor 4. J Exp Med, 2012. 209(13): p. 2395-408.

[34]Palova-Jelinkova, L., et al., Gliadin fragments induce phenotypic and functional maturation of human dendritic cells. J Immunol, 2005. 175(10): p. 7038-45.

[35]Nikulina, M., et al., Wheat gluten causes dendritic cell maturation and chemokine secretion. J Immunol, 2004. 173(3): p. 1925-33.

[36]Harris, K.M., A. Fasano, and D.L. Mann, Monocytes differentiated with IL-15 support Th17 and Th1 responses to wheat gliadin: implications for celiac disease. Clin Immunol, 2010. 135(3): p. 430-9.

[37]Palova-Jelinkova, L., et al., Pepsin digest of wheat gliadin fraction increases production of IL-1beta via TLR4/MyD88/TRIF/MAPK/NF-kappaB signaling pathway and an NLRP3 inflammasome activation. PLoS One, 2013. 8(4): p. e62426.

[38]Thomas, K.E., et al., Gliadin stimulation of murine macrophage inflammatory gene expression and intestinal permeability are MyD88-dependent: role of the innate immune response in Celiac disease. J Immunol, 2006. 176(4): p. 2512-21.

[39]Tuckova, L., et al., Activation of macrophages by gliadin fragments: isolation and characterization of active peptide. J Leukoc Biol, 2002. 71(4): p. 625-31.

[40]Ejsing-Duun, M., et al., Dietary gluten reduces the number of intestinal regulatory T cells in mice. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology, 2008. 67(6): p. 553-559.

[41]Langrish, C.L., et al., IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med, 2005. 201(2): p. 233-40.

[42]Evans, H.G., et al., In vivo activated monocytes from the site of inflammation in humans specifically promote Th17 responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2009. 106(15): p. 6232-7.

[43]Mesquita Jr, D., et al., Autoimmune diseases in the TH17 era. Braz J Med Biol Res, 2009. 42(6): p. 476-86.

[44]Sollid, L.M. and B. Jabri, Triggers and drivers of autoimmunity: lessons from coeliac disease. Nat Rev Immunol, 2013. 13(4): p. 294-302.

[45]Oldstone, M.B.A., MOLECULAR MIMICRY AND AUTOIMMUNE-DISEASE. Cell, 1987. 50(6): p. 819-820.

[46]Hadjivassiliou, M., et al., Autoantibody targeting of brain and intestinal transglutaminase in gluten ataxia. Neurology, 2006. 66(3): p. 373-7.

[47]Vojdani, A., et al., Immune response to dietary proteins, gliadin and cerebellar peptides in children with autism. Nutr Neurosci, 2004. 7(3): p. 151-61.

[48]Alaedini, A., et al., Immune cross-reactivity in celiac disease: anti-gliadin antibodies bind to neuronal synapsin I. J Immunol, 2007. 178(10): p. 6590-5.

[49]Dieterich, W., et al., Identification of tissue transglutaminase as the autoantigen of celiac disease. Nature Medicine, 1997. 3(7): p. 797-801.

[50]Molberg, O., et al., Tissue transglutaminase selectively modifies gliadin peptides that are recognized by gut-derived T cells in celiac disease. Nature Medicine, 1998. 4(6): p. 713-717.

[51]Vojdani, A., D. Kharrazian, and P.S. Mukherjee, The prevalence of antibodies against wheat and milk proteins in blood donors and their contribution to neuroimmune reactivities. Nutrients, 2014. 6(1): p. 15-36.

[52]Falth-Magnusson, K. and K.E. Magnusson, Elevated levels of serum antibodies to the lectin wheat germ agglutinin in celiac children lend support to the gluten-lectin theory of celiac disease. Pediatr Allergy Immunol, 1995. 6(2): p. 98-102.