Get Fitter in Just 3½ Minutes per Week

Around the New Year, diet and exercise resolutions feature prominently in many people’s lives. However, in most cases, these resolutions fail fairly quickly. Despite the beneficial impact of regular exercise on numerous health parameters, exercise participation and adherence in the general population remains poor,1 with “lack of time” being one of the most cited reasons why individuals fail at committing to a regular exercise program.2 Consequently, it would be prudent to examine effective exercise programs that do not require a significant time commitment—even as short as 3½ minutes per week.

NOTE: I wrote another article that covers some of the science behind supra-maximal interval training (SIT), a mode of exercise that creates physiological benefits with a minimal time investment. So, if you think this piece sounds too good to be true, I advise you to examine that article so that the protocol I’m about to describe to you is more believable.

An Exercise in Visualization

When I lecture about SIT, I perform a visualization activity. I ask the audience to close their eyes and imagine they are standing at the base of the stairs inside a football stadium. I tell them to ascend the stairs as fast as they can while I describe the many varied speeds that would be witnessed despite everyone putting forth the same relative effort. I also explain what everyone might be feeling at 15, 30, 45, and 60 seconds. Then, I have them compare the heaving breathing and the feeling of lactic acid in their lungs and muscles to an hour-long walk or slow jog.

After this, a simple question: which of these two training modalities do they think is going to stress them more to cause a physiological change to their cardiorespiratory and metabolic fitness? Most participants choose the all-out sprint as the method they believe would lead to greater physiological change.

After quantifying the number of steps attained, I state that everyone is done training for the day and—since they will inevitably feel some effects from that effort, they will have a day’s rest before returning to the stadium for their second stair-climb workout. I tell them we are going to continue doing this for 30 sprints, which will equate to two months of training, requiring just 3½ minutes per week!

To clarify this time commitment, it would take two weeks to complete seven “every other day” 60-second sprints, hence 3½ minutes per week.

Finally, the ultimate question: Does anyone doubt that on the 30th sprint you will be able to attain significantly more steps than you did back on day one? Intuitively, people understand that they would be able to do more steps on their last sprint compared to their first. And if this happens, by definition one is now fitter, since a greater amount of work has been accomplished in a given amount of time. So you can indeed improve your fitness in just 3½ minutes per week when the training effort is maximal or close to maximal.

Test this out for yourself: While continuing with your current level of activity, add just 3½ minutes per week of all-out sprinting and see what this accomplishes. There are different options on how to accomplish these sprints, but first let me describe an experiment I performed on myself.

The 60-Second Experiment

Since improvement is always harder when one is already very fit, I reduced my own training to the lowest possible quantity. Eliminating my own training for a few months led to a significant decrease in my maximal 60-second sprint speed (on a treadmill set to a 15% incline) from about 9 mph to around 7 mph.

I then embarked on an exercise protocol that involved sprinting on a treadmill (set at a 15% incline, for 60-seconds) every other day. I began at 7 mph, a speed previously established as a maximal or at least close to maximal effort. If the 60-second sprint was successfully completed, the subsequent sprint was done at a speed 0.1 mph greater than the preceding sprint, equivalent to running an additional 2.68 meters in 60 seconds. If the 60-second sprint was not successfully completed, the speed was not increased for the next sprint until it was successfully completed.

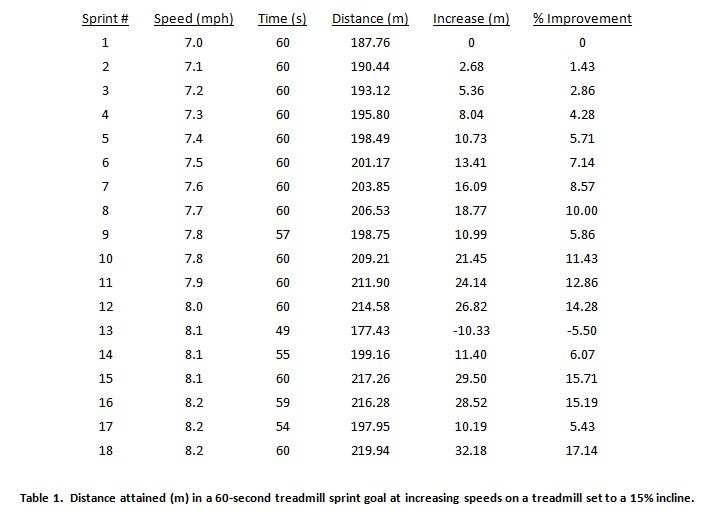

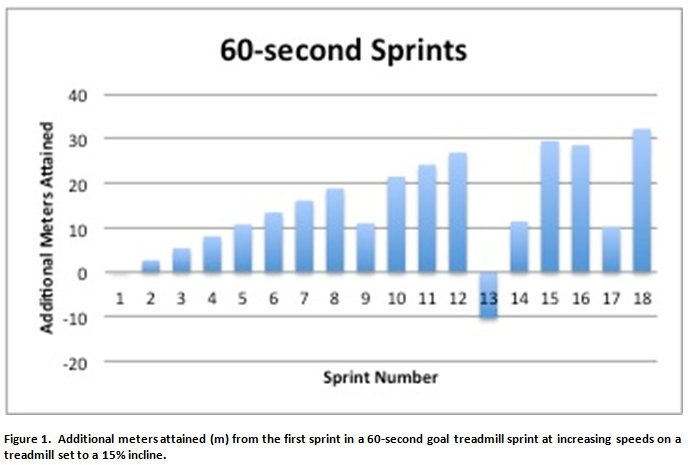

The protocol was conducted for five weeks, such that a total of 18 sprints were completed. Table 1 shows the speed, time completed (in seconds), meters attained, increase in meters from the first sprint, and percent improvement from the first sprint for each of the 18 sprints. Figure 1 displays the additional meters attained from the first sprint.

As both Table 1 and Figure 1 demonstrate, over the course of just five weeks, sprinting all-out for 60 seconds every other day resulted in an improvement of 32.18 meters (105.58 feet) from the first sprint, a 17.14% improvement. Note that not every sprint was successfully completed on the first attempt at the increased speed. When you are working at a maximal effort, there are many factors that influence performance, mental fortitude probably playing the largest role. But even when the sprint isn’t successfully completed, your system is still being significantly challenged and a training effect is still occurring. Consequently, over time, you will see an increase in performance albeit with a few peaks and valleys along the way.

Now, while this protocol will help you improve your fitness, I’m not suggesting that more sprints exponentially lead to more fitness. In fact, you might be thinking, If I’m going to make the effort to get to the gym, I might as well do a couple more sprints while I’m there! Of course, you can do more, but be careful how much SIT you do, as it is easy to overtrain.

Research has already shown that SIT for 8 minutes per week for just two weeks can both double endurance capacity3 as well as substantially improve insulin action,4 so doing significantly more than that likely isn’t necessary for most people. Additional exercise time could be better spent in other modes of exercise to improve strength and mobility, for example.

The 12-Minute Protocol

Since I began my interest in SIT back in the mid-1990s, the research has always suggested a similar quantity to that used in the above referenced research. As a consequence, I have used with my clients and recommended in lectures a 12-minute per week protocol that has proven very successful. This 12-minute protocol involves completing four sets of 60-second sprints, separated by a 4-minute recovery, three days per week. The three days also need to be separated by at least one day’s rest in order for the body to adapt and recover. A Monday, Wednesday, Friday timetable works well for many people.

It is important not to shorten the 4-minute recovery because if you do, you will not be able to maintain the power output attained in the first “all-out” effort interval. In fact, 4 minutes is a minimal recovery timeframe, and you can certainly take more recovery with no detriment to the training. I have often stated that having a very long recovery (e.g., an hour or more) is better because you will ultimately be able to increase your power output. It is not about “keeping your heart rate up” during the workout; the 60-second sprint itself is challenging enough.

Obviously, having an hour recovery is not the most time efficient if you’re doing this workout at the gym; however, if you have access to a modality at home or work, this approach can work very well. For example, many people have a tall enough staircase at their workplace that can work well for SIT as the impact is low while the intensity can easily become maximal.

I have conveyed this message to thousands of fellow healthcare professionals in my capacity as a lecturer for the Titleist Performance Institute, who, in-turn, have passed this on to their clients—and I have yet to hear that the protocol hasn’t significantly improved anyone’s health and performance. A year after one such lecture, a physical therapist approached me to thank me for the recommendation. He worked at a hospital and used the staircase in his building to run four sets of 60-second sprints throughout the day on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays.

A great benefit to spacing the sprints throughout the day is that you do not really perspire in just 60-seconds, so with a long recovery, you do not need to change into workout clothes (I would avoid running in high heels or restrictive work clothing, though). The physical therapist went on to tell me that he corralled a group of his coworkers to commit to the program along with him, and in doing so, was able to lose over 50 pounds over the course of the year! Pretty good for just 12 minutes per week!

There are many different modalities that can be used for SIT; but, for those where balance, mobility or joint issues come into play, the upright stationary bike is probably the best alternative. It also works well for everyone else, too. However, unlike for most treadmills, where the speed is pre-determined, upright stationary bikes set a resistance and the speed is dictated by the user. As a consequence, the speed is faster at the beginning and slows as fatigue develops with time, making 60 seconds feel like an eternity. So, if you choose to use an upright stationary bike, set the resistance as high as you can handle and complete the time prescription in 30-second increments rather than 60.

Final Thoughts

In closing, don’t give up on your New Year’s fitness resolution because you can’t commit to a plan that requires an amount of significant time. Hopefully you’ve seen that as little as 3½ minutes per week can go a long way when implemented with an all-out effort. And if you struggle to stay committed to your resolution, don’t give up for the long term—realize that you can get right back on track at any time with only a minimal amount of time required.

References

[1]Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, et al. Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet 2012; 380(9838): 247-57.

[2]Korkiakangas EE, Alahuhta MA, Laitinen JH. Barriers to regular exercise among adults at high risk or diagnosed with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Health Promot Int 2009; 24(4): 416-27.

[3]Burgomaster KA, Hughes SC, Heigenhauser GJF, Bradwell SN, Gibala MJ. Six sessions of sprint interval training increases muscle oxidative potential and cycle endurance capacity in humans. Journal of Applied Physiology 98: 1985-1990, 2005.

[4]Babraj JA, Vollaard NB, Keast C, Guppy FM, Cottrell, Timmons JA. Extremely short duration high intensity interval training substantially improves insulin action in young healthy males. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2009 Jan 28; 9:3.

Mark J. Smith, Ph.D.

One of the original members of the Paleo movement, Mark J. Smith, Ph.D., has spent nearly 30 years advocating for the benefits of Paleo nutrition.

More About The Author