Evolution and High Protein Diets Part 1

Although humanity has been interested in diet and health for thousands of years, the organized, scientific study of nutrition has a relatively recent past. For instance, the world’s first scientific journal devoted entirely to diet and nutrition, The Journal of Nutrition only began publication in 1928. Other well-known nutrition journals have a more recent history still: The British Journal of Nutrition (1947), The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (1954), and The European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (1988). The first vitamin was “discovered” in 1912 and the last vitamin (B12) was identified in 1948.1 The scientific notion that omega 3 fatty acids have beneficial health effects dates back only to the late 1970’s,2 and the characterization of the glycemic index of foods only began in 1981.3

Nutritional science is not only a newly established discipline, but it is also a highly fractionated, contentious field with constantly changing viewpoints on both major and minor issues that impact public health. For example, in 1996 a task force of experts from the American Society for Clinical Nutrition (ASCN) and the American Institute of Nutrition (AIN) came out with an official position paper on trans fatty acids stating:

“We cannot conclude that the intake of trans fatty acids is a risk factor for coronary heart disease.”4

Fast forward six short years to 2002 and the National Academy of Sciences, Institute of Medicine’s report on trans fatty acids5 states:

“Because there is a positive linear trend between trans fatty acid intake and total and LDL (“bad”) cholesterol concentration, and therefore increased risk of cardiovascular heart disease, the Food and Nutrition Board recommends that trans fatty acid consumption be as low as possible while consuming a nutritionally adequate diet.”

These kinds of complete turnabouts and divergence of opinion regarding diet and health are commonplace in the scientific, governmental and medical communities. The official U.S. governmental recommendations for healthy eating are outlined in the “My Pyramid” program6 which replaced the “Food Pyramid” – both of which have been loudly condemned for nutritional shortcomings by scientists from the Harvard School of Public Health.7 Dietary advice by the American Heart Association (AHA) to reduce the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) is to limit total fat intake to 30% of total energy, to limit saturated fat to <10% of energy and cholesterol to <300 mg/day while eating at least 2 servings of fish per week.8

Although similar recommendations are proffered in the USDA “My Pyramid,” weekly fish consumption is not recommended because the authors of these guidelines feel there is only “limited” information regarding the role of omega 3 fatty acids in preventing cardiovascular disease.6 Surprisingly, the personnel makeup of both scientific advisory boards is almost identical. At least 30 million Americans have followed Dr. Atkins advice to eat more fat and meat to lose weight.9 In utter contrast, Dean Ornish tells us fat and meat cause cancer, heart disease and obesity, and that we would all would be a lot healthier if we were strict vegetarians.10 Who’s right and who’s wrong? How in the world can anyone make any sense out of this apparent disarray of conflicting facts, opinions and ideas?

In mature and well-developed scientific disciplines there are universal paradigms that guide scientists to fruitful end points as they design their experiments and hypotheses. For instance, in cosmology (the study of the universe) the guiding paradigm is the “Big Bang” concept showing that the universe began with an enormous explosion and has been expanding ever since. In geology, the “Continental Drift” model established that all of the current continents at one time formed a continuous landmass that eventually drifted apart to form the present-day continents. These central concepts are not theories for each discipline, but rather are indisputable facts that serve as orientation points for all other inquiry within each discipline. Scientists do not know everything about the nature of universe, but it absolutely unquestionable that it has been and is expanding. This central knowledge then serves as a guiding template which allows scientists to make much more accurate and informed hypotheses about factors yet to be discovered.

The study of human nutrition remains an immature science because it lacks a universally acknowledged unifying paradigm.11 Without an overarching and guiding template, it is not surprising that there is such seeming chaos, disagreement and confusion in the discipline. The renowned Ukrainian geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky (1900-1975) said, “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.”12 Indeed, nothing in nutrition seems to make sense because most nutritionists have little or no formal training in evolutionary theory, much less human evolution. Nutritionists face the same problem anyone who is not using an evolutionary model to evaluate biology: fragmented information and no coherent way to interpret the data.

All human nutritional requirements like those of all living organisms are ultimately genetically determined. Most nutritionists are aware of this basic concept; what they have little appreciation for is the process (natural selection) which uniquely shaped our species nutritional requirements. By carefully examining the ancient environment under which our genome arose, it is possible to gain insight into our present day nutritional requirements and the range of foods and diets to which we are genetically adapted via natural selection.13-16 This insight can then be employed as a template to organize and make sense out of experimental and epidemiological studies of human biology and nutrition.11

The dietary protein conundrum: how much is enough?

An important dietary issue that has come under debate in recent years is the safety of high protein diets and their long term influence upon health and well being.17, 18 In the current U.S. diet the average protein intake is 98.6 g/day (15.5% of total energy) for men and 67.5 g/day (15.1% of total energy) for women.19 Animal products provide approximately 75% of the protein in the U.S. food supply followed by dairy, cereals, eggs, legumes, fruits and vegetables.20 Diets containing 20% or more of their total energy as protein have been labeled “high protein diets” and those containing 30% or more energy as protein have been dubbed “very high protein diets.”18 Accordingly, a “high protein diet” for the average U.S. male daily energy intake (2,618 kcal)19 would contain between 125 to 186 grams of protein per day and for the average female (1,877 kcal)19 between 89 to 133 grams of protein per day.

At this point, it should be noted that there is a physiological limit to the amount of protein that can be ingested before it becomes toxic.14, 21 A byproduct of dietary protein metabolism is nitrogen, which in turn is converted into urea by the liver and then excreted by the kidneys into the urine. The upper limit of protein ingestion is determined by the liver’s ability to synthesize urea. When nitrogen intake from dietary protein exceeds the ability of the liver to synthesize urea, excessive nitrogen (as ammonia) spills into the bloodstream causing hyperammonemia and toxicity.14, 21 Additionally excess amino acids from the metabolism of high amounts of dietary protein may become toxic by entering the circulation causing hyperaminoacidemia.14, 21

The avoidance of the physiological effects of protein excess has been an important factor in shaping the subsistence strategies of hunter-gatherers.22- 24 Multiple historical and ethnographic accounts have documented the deleterious health effects that have occurred when humans were forced to rely solely upon the fat depleted, lean meat of wild animals.22 Excess consumption of dietary protein from the lean meats of wild animals leads to a condition referred to by early American explorers as “rabbit starvation” which initially results in nausea, then diarrhea and eventual death.22 Clinical documentation of this syndrome is virtually non-existent, except for a single case study.25

Using known maximal rates of urea synthesis (MRUS) in normal subjects [65 mg N/h × kg (body weight )0.75] (range 55-76), it is possible to calculate the maximal protein intake, beyond which will exceed MRUS and result in hyperammonemia and hyperaminoacidemia.21 The mean maximal protein intake for the average weight U.S. male (189.4 lbs)26 is then 270 g/day (range 233-322 g/day), and for an average weight female (162.8 lbs),26 246 g/day (range 208-288 g/day). Consequently, “very high protein diets” for the average U.S. male could range from 187 to 270 g/day and for females, 134 to 246 g/day.

So let’s summarize a few key points. The average protein intake in the U.S. is about 15% of the normal daily caloric intake. Diets labeled as “high protein” contain 20-29% protein of the normal daily caloric intake, and diets with 30-40% protein are branded “very high protein.” It should be pointed out that this categorization is completely arbitrary and based almost entirely upon comparisons to the U.S. norm.

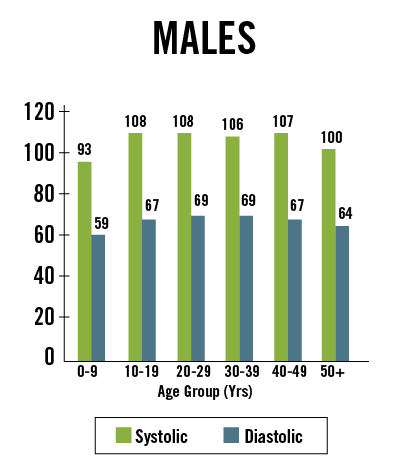

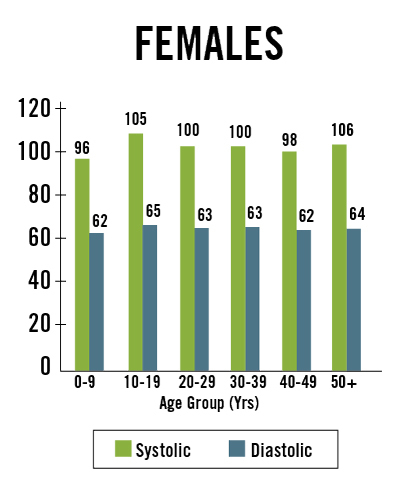

A salient question from an evolutionary perspective would be, “Is the average U.S. protein intake necessarily average or normal for our species?” For example, blood pressure in the U.S. and most other westernized countries is considered “normal” when systolic pressure is 120 mm Hg and diastolic pressure is 80 mm Hg. However, in many non-westernized people these values would be higher than normal. Consider the data in Figure 1 below showing blood pressure in the Yanomamo Indians of Brazil, a non-salt consuming society. Not only is blood pressure lower than normal western values, but it stays uniform throughout life and does not rise with age.27

In order to objectively answer the question whether or not high protein diets have detrimental or therapeutic health effects compared to the U.S. norm (15% total energy), we will frame this question from an evolutionary perspective before examining the experimental and epidemiological evidence in “Evolution and High Protein Diets Part 2” of The Evolutionary Basis for the Therapeutic Effects of High Protein Diets Series.

References

[1]. Bogert LJ, Briggs GM, Calloway DH. Nutrition and Physical Fitness, Ninth Edition. W.B. Sauders Company, Philadelphia, 1973.

[2] Dyerberg J, Bang HO. A hypothesis on the development of acute myocardial infarction in Greenlanders. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl. 1982;161:7-13.

[3] Jenkins DJ, Wolever TM, Taylor RH, Barker H, Fielden H, Baldwin JM, Bowling AC, Newman HC, Jenkins AL, Goff DV. Glycemic index of foods: a physiological basis for carbohydrate exchange. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981 Mar;34(3):362-6.

[4] No authors listed. Position paper on trans fatty acids. ASCN/AIN Task Force on Trans Fatty Acids. American Society for Clinical Nutrition and American Institute of Nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996 May;63(5):663-70.

[5] National Academy of Sciences, Institute of Medicine. Letter Report on Dietary Reference Intakes for Trans Fatty Acids, 2002. //www.iom.edu/CMS/5410.aspx.

[7] Willett WC, Stampfer MJ. Rebuilding the food pyramid. Sci Am. 2003 Jan;288(1):64-71

[8] Krauss RM, Eckel RH, Howard B, et al. Dietary Guidelines: revision 2000: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2000 Oct 31;102(18):2284-99.

[9] Blanck HM, Gillespie C, Serdula MK, Khan LK, Galusk DA, Ainsworth BE .Use of low-carbohydrate, high-protein diets among americans: correlates, duration, and weight loss. MedGenMed. 2006 Apr 5;8(2):5.

[10] Ornish D. Dr. Dean Ornish’s Program for Reversing Heart Disease: The Only System Scientifically Proven to Reverse Heart Disease Without Drugs or Surgery. New York : Random House, 1990.

[11] Nesse RM, Stearns SC, Omenn GS. Medicine needs evolution. Science 2006;311:1071.

[12] Dobzhansky T. Am Biol Teacher. 1973 March; 35:125-129.

[13] Cordain L, Eaton SB, Sebastian A, Mann N, Lindeberg S, Watkins BA, O’Keefe JH, Brand-Miller .Origins and evolution of the Western diet: health implications for the 21st century. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Feb;81(2):341-54.

[4] Cordain L, Miller JB, Eaton SB, Mann N, Holt SH, Speth JD. Plant-animal subsistence ratios and macronutrient energy estimations in worldwide hunter-gatherer diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000 Mar;71(3):682-92.

[15] Cordain L, Eaton SB, Brand Miller J, Mann N, Hill K. The paradoxical nature of hunter-gatherer diets: Meat based, yet non-atherogenic. Eur J Clin Nutr 2002; 56 (suppl 1):S42-S52.

[16] Cordain L, Watkins BA, Mann NJ. Fatty acid composition and energy density of foods available to African hominids: evolutionary implications for human brain development. World Rev Nutr Diet 2001, 90:144-161.

[17] Bravata DM, Sanders L, Huang J, Krumholz HM, Olkin I, Gardner CD, Bravata DM. Efficacy and safety of low-carbohydrate diets: a systematic review.

JAMA. 2003 Apr 9;289(14):1837-50.

[18] St Jeor ST, Howard BV, Prewitt TE, Bovee V, Bazzarre T, Eckel RH et al.. Dietary protein and weight reduction: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2001 Oct 9;104(15):1869-74.

[19] Wright JD, J Kennedy-Stephenson J, Wang CY, McDowell MA, Johnson CL, National Center for Health Statistics, CDC. Trends in intake of energy and macronutrients—United States, 1971-2000. JAMA. 2004;291:1193-1194.

[20] McDowell M, Briefel R, Alaimo K, et al. Energy and macronutrient intakes of persons ages 2 months and over in the United States: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Phase 1, 1988–91. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, Vital and Health Statistics; 1994. CDC publication No. 255.

[21] Rudman D, DiFulco TJ, Galambos JT, Smith RB 3rd, Salam AA, Warren WD. Maximal rates of excretion and synthesis of urea in normal and cirrhotic subjects.J Clin Invest. 1973 Sep;52(9):2241-9.

[22] peth JD, Spielmann KA. Energy source, protein metabolism, and hunter-gatherer subsistence strategies. J Anthropological Archaeology 1983;2:1-31.

[23] Speth JD. Early hominid hunting and scavenging: the role of meat as an energy source. J Hum Evol 1989;18:329-43.

[24] Noli D, Avery G. Protein poisoning and coastal subsistence. J Archaeological Sci 1988;15:395-401.

[25] Lieb CW. The effects on human beings of a twelve months’ exclusive meat diet. JAMA 1929;93:20-22.

[26] Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. Mean body weight, height and body mass index, United States 1960—2002 . Center for Disease Control. Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics, No. 347, October 27, 2004.

[27] Oliver WJ, Cohen EL, Neel JV. Blood pressure, sodium intake, and sodium related hormones in the Yanomamo Indians, a “no-salt” culture. Circulation. 1975 Jul;52(1):146-51.

Loren Cordain, Ph.D.

As a professor at Colorado State University, Dr. Loren Cordain developed The Paleo Diet® through decades of research and collaboration with fellow scientists around the world.

More About The Author